To the Editor,

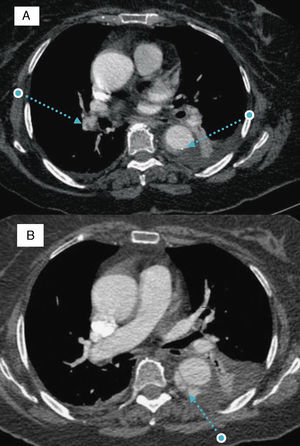

We present the case of a 77-year-old woman with morbid obesity and hypertension. She was admitted to the cardiology service after being diagnosed as having a type B aortic intramural hematoma (AIH). Three days later, she had a new episode of chest pain. The electrocardiogram revealed the presence of sinus tachycardia and the most important finding upon laboratory analysis was a new increase in D-dimer levels (which had been decreasing). Computed tomography was repeated and showed that the hematoma had not changed. However, arterial filling defects compatible with bilateral pulmonary embolism were observed (Figure 1A).

Figure 1. A: filling defects in right pulmonary arterial tree and type B aortic intramural hematoma. B: progression of the aortic intramural hematoma toward double barrel aortic dissection. Note the cobweb sign in the false lumen.

The decision was made to begin anticoagulation with sodium heparin. Eighteen days later, the patient had another episode of chest pain, this time with a decreasing D-dimer levels. Computed tomography demonstrated an increase in thickness of the AIH and dissection (double barrel) of the wall of descending aorta from its proximal portion to the diaphragmatic hiatus (Figure 1B). The decision was made to continue treatment with heparin, under strict clinical control.

After two weeks with no complications, the patient was discharged with oral anticoagulation therapy. Three months after the initial event, the dissection had progressed, with increases in the aortic diameter (from 36mm to 40mm) and in the false lumen (from 20mm to 24mm). Anticoagulation therapy was definitively terminated.

The originality of this case lies in the concomitance of an acute aortic syndrome and pulmonary embolism, since we have found no similar reports in the literature. These two conditions share similarities in their clinical signs and analytical results (D-dimer) at presentation and, thus, it is extremely important to make a correct differential diagnosis at the time of the acute phase. This difficulty becomes a real diagnostic challenge when the two conditions occur concomitantly. Although the role of the D-dimer levels in AIH has not been clearly established, as it has been in classic aortic dissection, there are series that confirm an increase in the incidence of AIH, although it is lower than that of dissection.

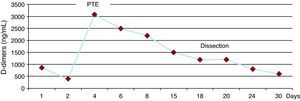

D-dimer titration as a predictor of the course of acute aortic syndrome has yet to be defined. In our patient, there was an increase in the concentration secondary to the embolism and, yet, it remained stable despite the progression of the AIH toward dissection (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Changes in D-dimer concentration over the course of the study of this case. PTE, pulmonary thromboembolism.

The dilemma arose at the time of therapeutic decision-making. Anticoagulation therapy has traditionally been avoided in these patients, although the subject is controversial and the documentation is limited. Ruggiero et al.1 reported the case of a man with chronic atrial fibrillation and type B AIH in whom an increase in the thickness of the hematoma was detected following reinitiation of anticoagulation therapy, and they suspended the treatment, to which they attributed a role in promoting rebleeding. On the other hand, Cañadas et al.2 described the cases of three patients with AIH and atrial fibrillation who received anticoagulation therapy during the acute phase; the clinical and morphological outcomes were satisfactory in all three.

In our case, given the limited knowledge concerning the role of anticoagulation therapy in the course of AIH, we decided to initiate treatment with heparin once pulmonary embolism had been documented, afterwards, the unfavourable course was confirmed. We do not know what role anticoagulation therapy plays in this complication; it may facilitate its development, although we also know that up to 36% of the cases of AIH evolve spontaneously to dissection.3

Once the presence of dissection had been established, another dilemma arose. Although the literature indicates that anticoagulation therapy could be associated with an increase in morbidity and mortality in these patients, there are no clear guidelines. On this occasion, treatment was maintained for 3 months after the embolism.

This case demonstrates the complexity involved in decision-making in patients with AIH who require anticoagulation, which will depend on a thorough evaluation of the risk-benefit balance. Even so, a comprehensive knowledge of the prognostic implications of anticoagulation therapy in acute aortic disease would be of great aid in decision-making. Studies involving larger samples of patients and long-term clinical and radiological follow-up would be necessary.

Corresponding author: aidasuarezb@gmail.com