To the Editor,

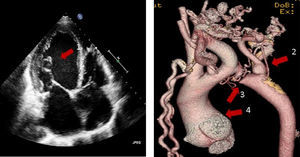

We present here the case of a 47-year-old patient with no past medical history of interest who went to the Accident and Emergency Department suffering from palpitations, progressive dyspnoea and orthopnoea. Examination revealed a II/IV systolic murmur; bibasal crackles; preserved and symmetrical pulses, albeit weak; blood pressure of 100/70mmHg and cardiomegaly on chest X-ray. An electrocardiogram revealed 2:1 atrial flutter with a ventricular rate of 150bpm. The emergency room, based on an initial diagnosis of suspected “tachycardiomyopathy”, administered digoxin, beta blockers, diuretics, and supplemental oxygen, thereby controlling the ventricular rate (75–100bpm) with rapid clinical improvement. The next day, an echocardiography was performed that revealed left ventricular dysfunction with ejection fraction of 35%, dilated aortic root, moderate aortic insufficiency, and an abnormal mitral subvalvular apparatus with very elongated chords with a myxoid appearance with moderate mitral regurgitation (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Left: echocardiography showing linear images within the left ventricular cavity corresponding to very elongated mitral chordae (1). Right: aortic CT with striking collateral circulation (2), an image of aortic interruption (3), and dilation of the aortic root (4).

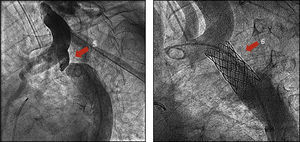

Given the new data, a multislice CT was performed, which showed a 49mm aortic root, severe aortic coarctation (Figure 1) and left atrial thrombus with no coronary abnormalities. Reviewing the basic diagnostic tests, the chest X-ray showed small costal notches that had gone unnoticed. The final diagnosis was left ventricular dysfunction by severe aortic coarctation with associated lesions of aortic and mitral insufficiencies. The rhythm became atrial fibrillation and cardioversion was not indicated by the left atrial thrombus. Cardiac catheterization was performed in an attempt to interrupt the aortic arch gradient of 40mmHg. A radiofrequency catheter was used to get past the coarctation, allowing subsequent dilation and stenting (Figure 2) with a disappearance of the gradient. At six months, the patient was asymptomatic, with an ejection fraction of 45% and being treated with dicoumarins, beta blockers and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors. Electrical cardioversion restored a sinus rhythm. Two months later, the ejection fraction was 55% and the patient remained in sinus rhythm and asymptomatic with slight mitral regurgitation.

Figure 2. Left: aortography showing aortic coarctation or interruption (5). Right: aortography after stenting, showing a normal aortic calibre (6).

“Zebras or horses?” This case clearly illustrates one of the basic axioms of medicine: “when you hear hoofbeats behind you, it is almost certainly the sound of horses and not zebras.” This can be translated as “what is most frequent is most likely.” The presence of 2:1 atrial flutter with severe ventricular dysfunction in a young man without any past medical history made us think of the most obvious: dilated cardiomyopathy secondary to tachycardia. However, the echocardiogram revealed valvular disorders (pronounced myxoid degeneration of the mitral chordae and aortic annuloectasia). A subsequent multislice CT revealed another previously undetected disorder (severe aortic coarctation). Reviewing the medical history, blood pressure was normal (which can be due to heart failure), and femoral pulses were present and symmetrical in the arms (possibly due to collateral circulation). Only after a careful review of the X-rays were the small costal notches observed. Coarctation of the aorta constitutes 6% of congenital heart disease in childhood and 15% in adulthood.1 Its clinical manifestations depend on severity: in mild cases the manifestations do not appear until adulthood, usually with the discovery of hypertension. In our patient, however, there were no disorders until the onset of acute heart failure. Percutaneous treatment with dilation of the coartation and stenting was decided upon, with good results.2

In our area, more than 90%–95% of heart failure cases are due to ischemic heart disease, hypertension, arrhythmias and valvular disease, but on occasion, as with this patient, the unexpected may happen. In this case, and contrary to all statistics and initial data, the sound of hoofbeats were those of a zebra and not of a horse.

Corresponding author. manuelp.anguita.sspa@juntadeandalucia.es