Recurrent pericarditis is probably the most common and troublesome complication of pericarditis, affecting about 20% to 30% of patients after a first attack of acute pericarditis.1–3 Recurrent pericarditis is defined as the recurrence of symptoms and signs of pericarditis after an arbitrary symptom-free interval of 6 weeks.4 A minimal symptom-free interval of 4 to 6 weeks after the index attack is important to avoid labeling incessant cases without resolution of the first attack of pericarditis as recurrences. Such incessant cases are also named as “incessant pericarditis” and do not represent a real recurrence.

Proposed diagnostic criteria for recurrent pericarditis include recurrent chest pain and 1 or more of the following signs: fever, pericardial friction rubs, electrocardiographic changes, echocardiographic evidence of new or worsening pericardial effusion, or elevated markers of inflammation (ie, elevated leukocyte count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, or C-reactive protein level).5 Many patients with a previous attack of pericarditis may experience recurrent pain but without a true recurrence documented by objective evidence of disease activity (ie, elevated C-reactive protein). This finding is important to avoid misunderstandings and unnecessary antiinflammatory therapies.6

The etiopathogenesis of recurrences is poorly understood and most cases remain idiopathic. However most cases are considered to be immune-mediated, although this has been only partially confirmed by the presence of either nonspecific or specific autoantibodies (ie, antinuclear antibodies, antiheart antibodies).7,8 Other cases may be related to an autoinflammatory disease (ie, familial Mediterranean fever) or an infective cause (usually viral either as chronic infection, reinfection or new infection, as demonstrated in up to one-third of recurrent pericardial effusions requiring pericardiocentesis).9,10 Some cases are the expression of a previously unknown neoplastic pericardial disease (especially lung cancer, but cases have been reported with breast cancer, lymphomas, and more rarely with primary cancer of the pericardium, especially pericardial mesothelioma). In clinical practice, several cases of recurrences may be especially related to inappropriate or incomplete treatment of the first attack or to a subsequent recurrence due either to dosage or treatment length.2,10

The aim of the present editorial is to briefly review current management strategies for recurrent pericarditis (antiinflammatory and immunosuppressive drugs, surgery) in order to provide the best evidence-based approach to the management of this complication.

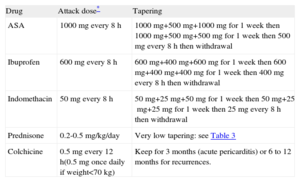

NONSTEROIDAL ANTIINFLAMMATORY DRUGSNonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug (NSAID) are the mainstay of pericarditis treatment (class I indication, level of evidence A).11 Various drugs have been proposed (especially acetylsalicylic acid, ibuprofen, and indomethacin) (Table 1). The largest published experience is with acetylsalicylic acid, which is also the preferred choice for patients who are already on antiplatelet therapy and have no contraindications to acetylsalicylic acid. Ibuprofen had been proposed in the 2004 European Society of Cardiology guidelines on the management of pericardial diseases, especially on the basis of expert consensus.12

Medical Therapy for Pericarditis: Practical Scheme in the Clinical Setting

| Drug | Attack dose* | Tapering |

| ASA | 1000mg every 8 h | 1000mg+500mg+1000mg for 1 week then 1000mg+500mg+500mg for 1 week then 500mg every 8h then withdrawal |

| Ibuprofen | 600mg every 8 h | 600mg+400mg+600mg for 1 week then 600mg+400mg+400mg for 1 week then 400mg every 8h then withdrawal |

| Indomethacin | 50mg every 8 h | 50mg+25mg+50mg for 1 week then 50mg+25mg+25mg for 1 week then 25mg every 8h then withdrawal |

| Prednisone | 0.2-0.5 mg/kg/day | Very low tapering: see Table 3 |

| Colchicine | 0.5mg every 12 h(0.5mg once daily if weight<70 kg) | Keep for 3 months (acute pericarditis) or 6 to 12 months for recurrences. |

ASA, acetylsalicylic acid.

Acetylsalicylic acid or a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug should be considered as first-line therapy with colchicine; prednisone is a second choice and may be added in more severe recurrence; colchicine is usually added to another antiinflammatory agent (see text for detailed explanation).

Attack dose usually until symptom resolution and C-reactive protein normalization then tapering, decreasing the dose every week. For patients intolerant to oral administration, refractory or with severe pain, temporary intravenous administration of an non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug or corticosteroid may be considered. Monitoring of C-reactive protein, blood count, creatinine, transaminases, and creatine kinase is recommended.

The choice should be based on individual response, previous medical therapy and local practice and expertise. It is essential to provide a full attack dose every 8h to achieve complete symptom control for 24h. This dose should be maintained until symptom resolution and C-reactive protein normalization, which is resolution of inflammation.13,14

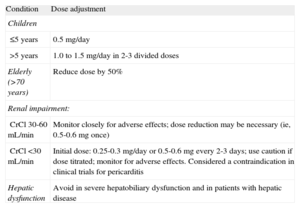

COLCHICINEColchicine at low, weight-adjusted doses (ie, 0.5mg once daily for patients under 70kg or 0.5mg twice daily for patients over 70kg) is a useful adjunct to an NSAID or a corticosteroid for all patients with acute and especially recurrent pericarditis (class I indication, level of evidence A). Specific dosing reduction may be considered (Table 2). At these low doses, the drug is well tolerated and may halve the risk of recurrences.5,15

Colchicine Dose Adjustment According to Age and Renal or Hepatic Dysfunction

| Condition | Dose adjustment |

| Children | |

| ≤5 years | 0.5 mg/day |

| >5 years | 1.0 to 1.5 mg/day in 2-3 divided doses |

| Elderly (>70 years) | Reduce dose by 50% |

| Renal impairment: | |

| CrCl 30-60 mL/min | Monitor closely for adverse effects; dose reduction may be necessary (ie, 0.5-0.6mg once) |

| CrCl <30 mL/min | Initial dose: 0.25-0.3 mg/day or 0.5-0.6mg every 2-3 days; use caution if dose titrated; monitor for adverse effects. Considered a contraindication in clinical trials for pericarditis |

| Hepatic dysfunction | Avoid in severe hepatobiliary dysfunction and in patients with hepatic disease |

CrCl, creatinine clearance.

Use in serious renal impairment is contraindicated by the manufacturer.

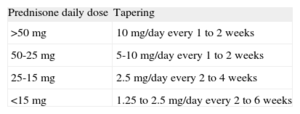

Corticosteroids should be considered as a second choice (class I indication, level of evidence A), for patients with contraindication to NSAIDs, lack of response to more than one NSAID or specific indications (ie, pregnancy, a systemic inflammatory disease requiring such therapy).16,17 When used, corticosteroids should be used at low to moderate doses (ie, prednisone 0.2 to 0.5mg/kg/day, or equivalent doses for other steroids, as attack dose for 2 to 4 weeks then slowly tapered), as is usual practice in rheumatology for the treatment of serositis in the setting of a systemic inflammatory disease (Tables 1 and 3). High doses (such as prednisone 1 to 1.5mg/kg/day) should never be used as first choice because they increase the risk of adverse side effects (up to 25%), hospitalization, and drug withdrawals and thus further recurrences.18

Tapering Regimen of Prednisone in Pericarditis, Very Slow Tapering Is Recommended Especially in Recurrent Cases

| Prednisone daily dose | Tapering |

| >50 mg | 10 mg/day every 1 to 2 weeks |

| 50-25 mg | 5-10 mg/day every 1 to 2 weeks |

| 25-15 mg | 2.5 mg/day every 2 to 4 weeks |

| <15 mg | 1.25 to 2.5 mg/day every 2 to 6 weeks |

Each decrease in prednisone dose should be only done if the patient is asymptomatic and C-reactive protein is normal, particularly for doses lower than 25mg/day.

For more difficult recurrent cases, a combination therapy (NSAID plus corticosteroid plus colchicine) may be considered to achieve symptom control, as is common practice for other medical conditions such as stable angina with a combination of possible different drugs (ie, nitrates, beta-blockers, calcium antagonists, ivabradine, and ranolazine).14

Weak evidence, mainly case reports and expert opinion, supports the use of other immunosuppressive drugs, usually prescribed for “refractory cases”. Such cases are not simply recurrent cases after steroid tapering, but are rather cases that require unacceptably high chronic dosages of corticosteroids to achieve disease control. In this condition, several drugs have been employed (azathioprine, cyclophosphamide, cyclosporine, methotrexate, hydroxychloroquine, intravenous immunoglobulin, anakinra).2 Azathioprine may be the preferred choice in adults, if tolerated (at the common dosage of 2mg/kg/day).19 The less toxic and less expensive drugs (eg, azathioprine) should be preferred, tailoring the therapy for each patient and according to the physician's experience.

PERICARDIECTOMYFor years, pericardiectomy has been considered as the last resort in recurrent cases of pericarditis. Specific indications have been given for recurrent cardiac tamponade or unacceptable complications following medical therapy, especially after corticosteroids, as well as true refractory cases to medical therapies. In my view, and in the view of most cardiologists specializing in the care of pericardial disease, pericardiectomy is an imperfect and unpredictable therapy that should be considered as treatment for recurrent pericarditis only after a thorough trial of medical therapy has been unsuccessful. In persons with ongoing symptoms and relapses despite medical therapy, however, pericardiectomy does appear to be a safe and frequently effective treatment option in experienced tertiary referral centers, as recently confirmed by a retrospective review of 184 patients treated at a single referral center from 1994 through 2005. Surgery for pericardiectomy appeared to be safe, with no deaths and only 2 major complications (1 stroke and 1 episode of bleeding requiring reoperation) in the immediate postoperative period and no significant difference in all-cause mortality over an average follow-up of 5.5 years. Additionally, patients treated with surgical pericardiectomy had significantly fewer relapses (9% vs 29%) than the medical treatment group.20

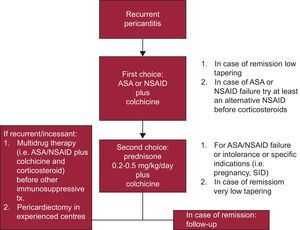

PROPOSED MANAGEMENT ALGORITHMAlthough European guidelines12 recommended hospitalization for diagnosis and monitoring of all patients with pericarditis, nowadays it seems reasonable to only admit patients with high risk features (ie, high fever, subacute course, large pericardial effusion, cardiac tamponade, and lack of response to empiric antiinflammatory therapy after at least 1 week), or if a specific etiology (nonidiopathic and nonviral) is suspected for any reason at presentation or during follow-up.21 Strenuous physical activity may trigger worsening of symptoms; therefore, such activity should be avoided until symptom resolution. Athletes should not participate in competitive sports until there is no longer evidence of active disease (eg, resolution of symptoms and normalization of inflammatory biomarkers). Although no supporting evidence is available, we ask patients to restrict exertion to a level necessary to perform domestic tasks and undertake sedentary work.2

A proposed practical management algorithm for recurrent pericarditis is reported in the Figure.

CONCLUSIONSAcetylsalicylic acid or NSAIDs are the mainstay of therapy of recurrent pericarditis with the adjunct of colchicine for several months. Corticosteroids are second choices and may favor chronification of the disease; therefore, they should be used only in patients with contraindication to NSAIDs, lack of response to more than one NSAID or specific indications (ie, pregnancy, a systemic inflammatory disease requiring such therapy). For more difficult recurrent cases, a combination therapy (NSAID plus corticosteroid plus colchicine) may be considered to achieve symptom control. Weak evidence, based mainly on case reports and expert opinion, supports the use of other immunosuppressive drugs, which should be reserved to the minority of true refractory cases to conventional antiinflammatory therapies (no more than 5% in my experience). Azathioprine is the preferred choice in adults, if tolerated. The less toxic and less expensive drugs should be preferred, and therapy should be tailored to each individual patient and according to the physician's experience. Pericardiectomy may be the last resort for true refractory cases in experienced tertiary referral centres.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTNone declared.