Both prior literature and reported managerial practices have claimed that the Balanced Scorecard is a management tool that can help organizations to effectively implement strategies. In this article, we examine some of the contributions, dilemmas, and limitations of Balanced Scorecards in health care organizations. First, we describe the evolution of Balanced Scorecards from multidimensional performance measurement systems to causal representations of formulated strategies, and analyze the applicability of Balanced Scorecards in health care settings. Next, we discuss several issues under debate regarding Balanced Scorecard adoption in health care organizations. We distinguish between issues related to the design of Balanced Scorecards and those related to the use of these tools. We conclude that the Balanced Scorecard has the potential to contribute to the implementation of strategies through the strategically-oriented performance measurement systems embedded within it. However, effective adoption requires the adaptation of the generic instrument to the specific realities of health care organizations.

Keywords

In a recent study, Bohmer1 identified 4 habits that distinguish the most successful health care organizations and obtain the best outcomes. The 4 habits identified were: a) setting objectives and outlining the means to achieve them; b) a focus on the design of the organization, its policies, and its physical and technological infrastructure; c) measurement and monitoring of outcomes, and d) ongoing review of clinical practice in the context of available scientific evidence. Whilst acknowledging the importance of each of these habits, in this article we propose to address several aspects related to the third habit (ie, the issue of measurement in health care organizations).

Our starting point is that a proper formulation of strategy (goal planning) and its subsequent implementation and evaluation (measurement and monitoring of outcomes) is critical to the lasting success of any organization. From that starting point, the purpose of the present article is to review ways in which a specific management tool, the Balanced Scorecard (BSC), can lead to improvements in strategic management and in particular to better strategy implementation and evaluation. More specifically, we will review the contributions, dilemmas, and limitations associated with adopting the BSC in health care organizations.

In the first section, we introduce measurement and performance monitoring as a key aspect of strategic management in health care organizations and identify the BSC as a potentially useful tool, which is often used for this purpose. We then describe the basic characteristics and evolution of the BSC and highlight aspects to take into account when considering its adoption as a management tool in health care organizations. In organizing the discussion, we distinguish between aspects related to the design of the BSC and aspects related to its use.

The measurement and monitoring of results as a key issue in the strategic management of health care organizationsInterest in strategic management in hospitals and health care organizations is not new. Back in the 1980s, with the modernization of the health system, many health organizations began to adopt formal processes to formulate strategy. The process was most widespread in the late 1990s, when the former National Institute of Health (NIH), under the direction of Alberto Núñez Feijoo, developed a corporate strategic plan and then invited all public hospitals in the NIH to produce their own strategic plans. A similar process has occurred in other countries. For example, since 1991, all public hospitals in France have been obliged by law to submit a 5-year strategic plan (Projet d’établissement).2

Although the formulation of strategies derived from strategic planning exercises is a key factor in the superior results achieved by some health care organizations, it is not in itself a sufficient basis for success. In fact, various studies indicate that most strategies that fail do not fail because they are poorly designed or planned, but because they are poorly implemented.3, 4, 5 In other words, while devoting resources and talent to careful strategic planning may be justifiable, organizations need to take as much care to ensure that those plans are properly executed and implemented. In that sense, at least in organizations of a certain size and complexity, formal systems to measure and monitor results are essential to guide and assess implementation.6 Consequently, the measurement and monitoring of results is one of the 4 key habits or factors mentioned above.

In the mid-1990s, the BSC began to gain popularity as a management tool that could be used to measure and monitor results from a novel perspective, thereby contributing to strategy implementation. Initially developed outside the health care arena, the BSC was used in health care from the late 1990sonwards.7, 8 It was widely used in individual centers, while one of the pioneering international experiences in large-scale use of the instrument was led by the Ontario Hospital Association (Canada). This association, along with the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care, decided to adopt the BSC to evaluate the performance of the region's 89 hospitals, with the first application in 1998.9 The report from that edition outlined performance indicators structured in 4 areas: a) clinical management and outcomes; b) patient perceptions of the hospital; c) financial performance, and d) system integration and change. In the first 2 editions, information was generated on the entire hospital. Since 2001, however, BSC have also been developed for the different hospital services (emergency, critical care, nursing).

In recent years, progress has been made in incorporating measurement and performance systems within strategic management. This is also true of the Spanish health care sector. Currently, the regional health services of all of Spain's autonomous communities have developed performance measurement systems based on indicators of cost, activity, and quality.10 Some of them have explicitly used the BSC model for this purpose. Two experiences are particularly relevant here, although they are not the only ones. First, one of the objectives within the Osakidetza (Basque Health Service) 2003-2007 Strategic Plan was that all service organizations within the Osakidetza should have a strategic plan and a BSC by the end of that period. For its part, the Valencian Health Agency, which was legally constituted in 2005, submitted its first strategic plan in January 2006.11 Notable aspects of the plan included the participation of professionals in its development, the adoption of the BSC and strategic map as tools to guide implementation of the strategic plan and performance monitoring, and alignment between the Valencian Health Agency and health departments through a process of informing each of the 22 departments of health of this plan.

The balanced scorecardSeveral studies in Europe and North America have shown that between 30% and 60% of medium-size and large organizations have significantly revised their measurement systems in the last 10 years.12, 13 The BSC is one of the most widely used of the new generation of performance measurement systems. For example, a recent report by the Bain consultancy14 indicated that, of a total sample of over 1200 large companies, 44% used outcome measurement systems such as the BSC or similar.

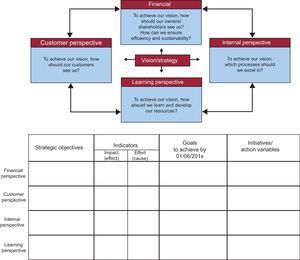

Indeed, the purpose of the BSC, as it was originally conceived, was to address problems relating to the measurement of organizational performance (Figure 1). As pointed out by Kaplan and Norton, the authors of the BSC, the systems traditionally used to measure results in the vast majority of organizations, centered exclusively, or almost exclusively, on financial indicators. In some sectors (such as health) in which non-financial indicators were widely used for operational (clinical) management, there was an undesirable dichotomy between the economic vision of the management teams and the clinical view of the health care professionals, and measurement systems were not able to effectively integrate or build bridges between the 2 visions. The traditional systems used to measure results had several problems, although they can, for the purpose of simplification, be grouped into 2 blocks. On the one hand, either because of an over-emphasis on financial indicators or because financial indicators are not sufficiently integrated with other indicators, the traditional systems provide little in the way of multidimensional and integrated support for managerial decision-making. Financial indicators are, by definition, lagging indicators; they capture the impact of decisions taken but do not provide information on the drivers of financial outcomes nor how they might be used to achieve the desired results. Moreover, the absence of effective integration between financial and other indicators provides mixed signals about the persistence of long-term success.

Figure 1. Initial formulation of the Balanced Scorecard.

On the other hand, an emphasis on exclusively financial results or the unstructured enumeration of different types of indicators does not provide management with a clear picture as to how well strategy is being implemented or what actions are needed to effectively implement it.

The first generations of BSC therefore proposed new avenues for measurement systems through a structured combination of financial and non-financial metrics with strategic implications. Expressed in its simplest form, a BSC will: a) identify the key perspectives needed to provide a multifaceted view of organizational performance; b) identify strategic objectives for each of those perspectives, and c) select indicators and targets for each of the objectives (though only after the strategic objectives have been established) (Figure 1).

It is true that other management tools that aimed to combine financial and nonfinancial indicators existed before the BSC (eg, dashboards, etc.). In this sense, one could argue that the first generations of the BSC were not, in themselves, a revolutionary innovation. However, despite their good intentions, most of the earlier attempts did not achieve their purpose and generally ended up focusing on indicators from a single dimension. In the traditional dashboards of many organizations, the tendency was to concentrate exclusively on financial indicators. Within the health sector, traditional dashboards tended to focus on activity indicators. Moreover, the deployment of schemes such as Management by Objectives led to a focus on strategic operational indicators. None of these earlier attempts provided a true structured combination of financial and nonfinancial metrics with strategic implications.

How does the BSC avoid falling into the same trap? First of all, this trap is avoided because it is based around an explicit reflection on the different perspectives needed to provide an overview of multifaceted organizational performance. In its initial formulation, the BSC aimed to establish objectives and indicators from 4 perspectives: a) financial; b) clients or users; c) internal processes, and d) learning and resource development. However, the tool is flexible both in terms of the number of perspectives that can be considered as well as with regard to which specific perspectives need to be incorporated to represent a particular organizational reality. A second way in which the BSC avoided the errors inherent in earlier proposals was simply by proposing a pattern or template that graphically highlights the presence of multiple perspectives (Figure 1). It is therefore less likely that managers who design or use the instrument will limit their choice to indicators with a single dimension.

In short, the first generation of BSC implied the multidimensional measurement of results based on the integration of financial and nonfinancial indicators, and highlighted the advantages of this approach compared with the battery of exclusively financial, activity–or operationally-based–indicators or the mere unstructured enumeration of indicators.

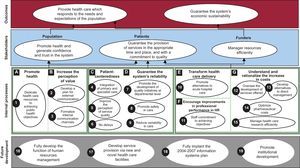

As they developed their proposals, Kaplan and Norton realized that, although BSC represented a qualitative improvement in performance measurement systems, the first generation of these instruments did not fully ensure that the chosen indicators were indeed drivers of success in an organization or that the strategies actually ended up being implemented. They therefore evolved the model by proposing that, when developing a BSC, the starting point should not be either the targeting or the selection of new metrics (and certainly not the mere classification of an existing metric from a number of different perspectives). On the contrary, they suggested that for the second generation of BSC the starting point should include a narrative description of strategy, expressed in highly concrete terms. They therefore suggested that classification of the strategic objectives in the form of perspectives (eg, financial, client, process, learning) should help to identify causal relationships between objectives and, ultimately, allow effective graphical representation of the strategy. Consequently, strategy maps became a basic component of the second generation of BSCs (Figure 2). A strategy map is a graphic, highly visual representation of an organization's strategy; it is set out in a logical fashion, which helps to illustrate how the strategy will be implemented through a series of cause-effect relationships between objectives. It also relates, for example, the development of resources (people, technologies, information systems, etc.) with the quality of internal processes or the intensity of innovation with a portfolio of products or services, and thereby links the various objectives with the final results or intended effects. Strategy maps are therefore the foundation for the second generation of BSC (although the specification of indicators often leads to a further review of the strategic map). In other words, the mission of the second generation of BSC is to provide relevant indicators to measure the objectives outlined in the strategy map. The indicators are chosen only after strategic objectives are defined in the strategy map.

Figure 2. Basic example of a strategic map.

In short, while early versions of the BSC prioritized the idea of multidimensional measurement of business performance, the second generation of BSC, with the introduction of strategic maps, evolved towards the description or narration of the strategy.

Design of the basic scorecard in health care organizationsThe BSC has become more widely used in health care organizations over the last decade. The first article by Kaplan and Norton on the BSC was published in 1992,15 and the first article specifically about the use of the BSC in the health sector appeared in 1994.16 Nevertheless, this instrument did not become more widely used in the health care sector until the end of the 1990s and the beginning of the new century. The first articles on its use in the health care sector in Spain appeared in 2002.17 A recent study based on a survey carried out in 218 public hospitals in Spain showed that it was not yet widely used. 18 The study indicated that 28% of the hospitals surveyed did not use the BSC and that in 52% it was only used to a small degree. The authors found that younger executives and those with less time in their posts were more likely to use the BSC, and that they thought it made a positive contribution in terms of implementing strategies to control health care costs and provide greater managerial flexibility.

While use of the BSC has gradually increased in the health care sector in recent years, it has also become clear that, as a generic tool, it needs to be adapted to the realities of the sector and the realities of each organization. Fortunately, the BSC is sufficiently flexible to allow for variations to fit each strategic situation. Nevertheless, several challenges or dilemmas arise when considering implementation of the BSC in a health care organization, above and beyond those issues that inevitably arise when starting any specific project with a BSC. We will consider those sector-specific issues here, and will distinguish between aspects related to the design of the BSC and those related to its application.

Which Perspectives Should be Considered?In the aforementioned study on the adoption of the BSC in the Spanish health sector, we note that although most of the experiences cited the 4 classical perspectives of the BSC, the majority of directors felt that “there was room for improvement in terms of adapting the instrument to the specificities of the hospital environment”.18 In the case of the health care sector, this often meant adapting the classical financial perspective to the idiosyncrasies of public health or not-for-profit organizations.

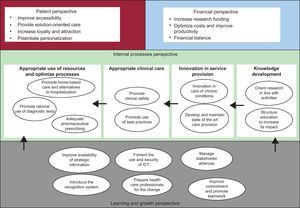

A frequently used variation has been to expand the scope of the financial perspective from pure “economic-financial results” to the broader concept of “organizational results”. In that way, 2 sub-areas can be included (ie, economic performance and improvements in population health). In the case of publically funded hospitals the client perspective has sometimes been extended to include other stakeholders (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Example of a strategic map with the financial perspective modified by results and the client perspective, by stakeholders. HR, human resources.

In other adaptations, new perspectives were included.19, 20 For example, some organizations added a fifth perspective on clinical outcomes. In other experiments, one of the 4 perspectives included in the initial formulation of the BSC was replaced. A case in point was the hospital report on the Ontario Hospital Association cited above, in which the process perspective was replaced by a clinical management and outcomes perspective.

Balanced Scorecard With or Without a Strategic Map?As already mentioned, the first generation of BSC emphasized a balance between perspectives, leading to a focus on stakeholder satisfaction (Figure 1). None of the perspectives dominated the others, and it was this balance that facilitated a multifaceted profile that was useful in decision making and in measuring and monitoring the creation of long-term value. Interestingly, the balance between different perspectives that characterized the first generation of BSC gave way in the second generation of BSC to an approach that used a hierarchy of perspectives, via strategy maps. In this approach, some perspectives are considered a means to achieving success in other perspectives (ie, those that embody a company's final aim) (Figure 2, Figure 3).

Organizations need to determine which of these 2 approaches is better suited to their situation. Although the BSC model has evolved towards the incorporation of strategy maps, that does not necessarily mean that organizations adopting the BSC have to use a second-generation BSC with a built-in strategy map, even though there may be strong arguments for doing so. Some organizations believe that the hierarchical approach employed in the second-generation models helps them to more effectively represent their business model, making it easier to choose indicators and targets and to reflect on the implications of decisions and actions throughout the map. However, other organizations may feel more comfortable with a format that does not establish hierarchies and will therefore prefer to work with first-generation models (Figure 1). This is especially likely in cases where cause and effect relationships between objectives are neither simple nor unidirectional (ie, always in the same direction, from mid-term to final perspectives), but are rather cyclical and multidirectional and which involve conflict and compromises, as well as in those in which no perspective or stakeholder takes priority over the others.

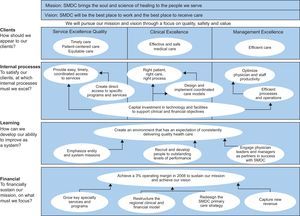

How Should the Perspectives be Ordered?If we decide to incorporate a causal map into the BSC, then the question arises as to what is the appropriate “order” for the perspectives? In the initial formulation, the usual order is (from bottom to top) learning and growth, internal processes, clients, and, lastly, financial performance (Figure 2). This indicates that the cause-effect chains are predominantly in that direction. In early experiences using the BSC in health care organizations, this sequence was often accepted as appropriate. However, there has been increasing resistance within health care organizations, especially those in the public sector, to placing the financial perspective at the apex of the strategy map. If a perspective is placed at the apex of a strategy map it means, in short, that the objectives associated with that perspective represent the organization's ultimate goal (whilst the objectives associated with other perspectives are only a means to achieving that goal). For that reason, in some recent versions of the strategy map, client and financial perspectives are placed at the same level, at the apex, thus assigning them equal importance (Figure 4). Alternatively, some organizations have chosen to include a fifth perspective, which refers to the organization's mission and purpose. This can be positioned above the financial perspective to highlight the fact that financial results contribute to achieving the organization's final objective.

Figure 4. Example of a strategy map with the financial and client perspectives at the same level. ICT, information technology and communication.

In some public hospitals, it has been proposed that the financial perspective should be placed on the lower tier of the strategy map. The underlying idea is that economic and financial resources allow investment in skills and growth (attracting talent, conducting research and innovation, training professionals, investment, etc.), resulting in better internal processes and ultimately better outcomes for clients. In this sense, the case of the Saint Mary's Duluth Clinic in Minnesota is interesting. This clinic was one of the first health care institutions to use the BSC, which it adopted in 1999. Since then, the BSC has been updated yearly, and in 2006 the center decided to place the financial perspective at the bottom of strategic map, as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Saint Mary's Duluth Clinic Balanced Scorecard. SMDC, Saint Mary's Duluth Clinic.

Each BSC strategic map is unique, and will reflect the idiosyncrasies and strategic focus of individual organizations. It is impossible, therefore, to propose a strategy map format, a cause-effect sequence, or a BSC that will be universally valid. Thus, when management teams are considering adopting a BSC, they should not expect the tool to provide a default response, but rather should use it as an aid to help them explicitly represent the management team's shared mental map of how the business model or activity of a specific organization should look

Using the balanced scorecard in health care organizationsIn addition to the points raised on how to design the BSC so that it fits specific situations, health care organizations face other dilemmas and challenges associated with the use of the instrument.

Where to Begin?The formulation of organizational strategy should be driven by senior management21 and the strategy should be adapted consistently for each level of the organization (ie, from corporate strategy [the whole organization] to strategy at the level of units [services or clinical management units]), as noted in the article in this series on strategic planning.22 Since one purpose of the BSC is to assist in strategy implementation, it is not surprising that senior management is considered the logical starting point for developing a BSC within an organization. If strategy is established by senior management, then that is where the BSC should begin to be unrolled. According to the logic of the BSC, from that point on there is a subsequent cascade process, in which the strategic objectives at the highest level define strategic objectives at the level of subunits or the next level of services, and so on. Consequently, the strategy maps and BSC developed by senior management transfer to the strategy maps and BSC at levels reporting to senior management, so as to ensure alignment between all of the maps and among all of the BSC. As the strategy maps and BSC move toward improving alignment between units, they are no longer mere instruments to measure performance or to describe strategy and instead become key factors in implementing strategy in subunits or services.

The question here is how reasonable it is to expect that this hierarchical, top down sequence of development of the BSC will be universally applicable. Can I develop the BSC for the cardiology department if I do not know the BSC of the hospital? (This is often associated with a prior question: how can I formulate and implement the strategy for the cardiology department if I do not know the hospital's strategy?). In some circumstances, this bottleneck can be solved through better communication. In the event that a BSC or a strategy for the hospital does exist but is not known to the service manager, he or she must be informed of the contents of the BSC (or the strategy) to continue with the process of a top down cascade for the BSC. But what if there is no BSC for the hospital? What if no strategy has been formulated for the hospital? In that case, does it make sense to develop a BSC for an organization at the service level? Or, more generally, does it make sense to begin to develop a BSC at the level of subunits rather than at the level of senior management?

In this type of situation, we would recommend that BSC is initiated at the highest level of the organization in which there is a defined and explicitly formulated strategy, and to cascade downwards to lower levels in the organizational structure. This means that, if there is no explicitly formulated strategy at higher levels but there is one at a lower level, then it can make sense to begin to adopt the BSC at the lower level. There is a difference between this and a situation in which the upper level has explicitly formulated a strategy but has no desire to implement a BSC. In this context, and to the extent that a lower-level strategy has been formulated in line with the top level, it can also be reasonable to take the initiative to adopt the BSC in the lower level. A variation of this situation occurs when senior management requests a given subunit to act as a pilot center to assess the experience of adopting the BSC, to learn from it, and, if necessary, to later extend it to the rest of the organization. In all these situations, it is important that senior management is aware of the adoption of BSC initiatives at lower levels, to prevent subunits implementing strategies that are not in line with overall strategy.

What Should I Use the Balanced Scorecard for?As with any performance measurement system, the BSC has multiple uses. It can be used, for example, to facilitate managerial decision-making, either individually or as a team, by emphasizing planning, policy focus, detecting warning signs or opportunities, or monitoring corrective actions, etc. It can also be used to ensure congruence of objectives between management levels, by focusing on issues such as accountability, evaluation, and incentive systems.

In both the literature and in real-life applications, it is often proposed that the BSC should be used to pursue both goals simultaneously. At first glance, if the BSC is used in planning and to facilitate decision-making, it would seem logical to extend its use to goal-setting as well, and to tie managers’ evaluations and compensation to their degree of success in achieving those goals.

However, this premise should not be accepted automatically. Although using the BSC to make management objectives (including evaluation and compensation) more consistent can motivate managers to achieve better results, it should be noted that using the BSC both to facilitate decision making and as a basis for evaluation and compensation can lead to opportunistic behavior (ie, the goals set may be too ambitious or, conversely, too easily achievable and therefore biased downward or upward depending on the information available to the parties involved). If this type of bias is introduced into the system of evaluation and goal setting, the primary purpose of the measurement system (ie, to facilitate decision-making based on realistic scenarios) can be impaired. When implementing the BSC, an organization must assess the relevance of these considerations in their particular context. Whenever a BSC is implemented, it is important to note that the BSC can be used both to facilitate decision-making and as a basis for evaluation and fixing incentives, but that users should distinguish between these 2 ends and not consider it strictly necessary to employ them both simultaneously.

Which Indicators Should be Considered?Since the measurement of performance is an inherent goal of the BSC, it is essential to use the appropriate indicators. The BSC therefore needs to be particularly sensitive to 2 issues (ie, the relevance and availability of indicators).

The relevance of an indicator is concerned with issues such as whether it is sufficiently sensitive and specific to measure performance, and what we mean by performance in the different perspectives used. We also need to determine whether clinicians and managers share a common vision about what the most relevant indicators are, as they will often have different and/or contradictory views about performance. These can become particularly evident with regard to the indicators used to assess financial and client perspectives. In this respect, strictly financial indicators such as debt ratio, rate of debt coverage, etc., should probably be given less weight, while greater importance should be placed on clinical-economic indicators stemming from exploitation of the minimum basic data set. These can include average length of stay adjusted for case complexity, complexity-adjusted cost per case, pharmaceutical costs, etc., and indicators of cost-effectiveness.

Within the client perspective, it is advisable to go beyond indicators of satisfaction and client orientation, to include indicators of health outcomes, quality, patient safety, and accessibility. The Table 1 gives some examples of indicators from the client perspective.

Table 1. Examples of Indicators in the Client Perspective

| Goal area | Examples of indicators |

| Patient safety | Nosocomial infection |

| Central catheter-related bacteremia in the ICU | |

| Patients with surgical safety checklist | |

| Number of notified adverse events | |

| Health outcomes | Risk-adjusted mortality rate (AMI, etc.) |

| Percentage of patients with AMI and coronary angiography | |

| Percentage of patients with controlled blood pressure | |

| Cardiovascular mortality rate | |

| Accessibility | Mean time to first consultation |

| Time to appointment for complementary tests | |

| Mean time in days on waiting list for surgery | |

| Diagnosis-to-treatment interval |

AMI, acute myocardial infarction; ICU, intensive care unit.

Strategies often fail in organizations, including health care organizations, not because of poor design but because they are poorly implemented. Since strategy implementation is critical to the continued success of any organization, the study of specific management tools that can help in this regard is of great interest. In this article, we have reviewed some of the contributions, dilemmas, and limitations pertaining to one particular management tool, the BSC, in the hope that it will be better implemented and evaluated in health care organizations. In its initial formulation, the BSC was conceived as a multidimensional measurement instrument that integrated financial and nonfinancial indicators. This proposal had advantages over the use of batteries of purely financial indicators, or those based on activities and operations, or the mere unstructured enumeration of indicators, which traditional dashboards used to consist of. The BSC has subsequently evolved toward the incorporation of strategy maps (ie, shared mental maps of the cause-effect sequence representing an organization's business model).

When considering the adoption of the BSC as a management tool in health care organizations, it is essential to take into account the specificities of the sector. Consequently, this article distinguishes between the design aspects of the BSC and those relating to its application. Concerning the design, information is provided to address 3 key concerns: a) which perspectives to consider; b) the implications of incorporating a strategy map, and c) ordering the perspectives in a cause-effect sequence. This article also proposes a series of reflections on using the BSC in health care organizations (ie, the organizational level at which to initiate adoption of the BSC, the distinction between the use of the BSC to facilitate decision-making and to provide incentives, and which indicators to use).

In its translation to the field of health management, both theoretical developments and actual experiences with the application of the BSC have shown the need to adapt the generic tool to the realities of the sector and to each organization. Fortunately, while bearing in mind that adaptations will be required, the BSC has proven to be sufficiently flexible to fit different strategic situations and can thereby help to improve strategy implementation and the measurement and monitoring of results in health care organizations.

Conflicts of interestNone declared.

Corresponding author: ESADE Business School, Universitat Ramon Llull, Avda. Pedralbes 60-62, 08034 Barcelona, Spain. josep.bisbe@esade.edu