To describe the results of the analysis of pacemaker implantations reported to the Spanish Pacemaker Registry in 2011, with particular reference to the population distribution and the selection of pacing modes.

MethodsInformation provided by the European Pacemaker Patient Identification Card was processed using a purpose-built computer application.

ResultsData from 115 hospitals were analyzed, totaling 13 373 cards, representing an estimated 38% of implantations. The number of pacemaker generators and resynchronization devices implanted was 738 and 56.2 units per million population, respectively. The mean age of the patients who received a device was 76.7 years. Overall, 57.2% of first implantations and 56.5% of replacements were performed in men. Most implantations (38.7%) and generator replacements (41.9%) were performed in patients aged between 80 and 89 years. Of the pacemaker leads used, 99.7% were bipolar and 63% used an active fixation system. Overall, 20% of the patients with atrioventricular block or sick sinus syndrome were paced in VVI/R mode despite being in sinus rhythm.

ConclusionsWith respect to previous years, the use of conventional pacemakers remained stable and the implantation of resynchronization devices has increased. The number of implantation procedures continues to be higher in men and in younger patients. Age and the degree of blockage remain as factors influencing the appropriate choice of pacing mode.

Keywords

In an attempt to raise awareness on the current situation of cardiac pacing and the degree of compliance with the recommendations of the current clinical practice guidelines,1, 2, 3 the Spanish Pacemaker Registry, the Banco Nacional de Datos de Marcapasos, aims to publish an annual report. In fulfillment of this aim, this report presents the most salient data on cardiac pacing and current progress in Spain in 2011.

The first official report was published in the Revista Española de Cardiología 1997,4 and since then has been periodically issued,4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 although originally the data were obtained by survey and published in 1989.14 Detailed information for every year since 199915 is available on the web page of the Working Group on Cardiac Pacing.

MethodsThe analysis of the pacemaker registry was based on information from the following sources:

Report of the Spanish Institute of StatisticsThe population data used for the various calculations were extracted from the latest definitive report updated by the Spanish Institute of Statistics to January 2011. There may, therefore, be a slight mismatch regarding the number of inhabitants, as the estimate of residents in Spain for 1 January 2012, based on the preliminary census data, indicated an increase of 22 497 people.16

Information Provided by Various DistributorsAs on previous occasions, the registry did not receive all the European Pacemaker Patient Identification Cards; information on the total number of pacemakers implanted and their distribution by autonomous region was collected in collaboration with the commercial distributors in Spain. This information was also provided to the European Confederation of Medical Suppliers Associations (EUCOMED). Under current legislation, it is mandatory to send information on all the procedures conducted to the Banco Nacional de Datos de Marcapasos (Royal Decree 1616/2009, 26 October, regulating active implantable medical devices17), although currently the registry data are provided voluntarily by health professionals.

European Pacemaker Patient Identification CardsOnly the data provided on the European Pacemaker Patient Identification Card are processed. The cards contain coded fields for symptoms, etiology, electrocardiographic indications, pacing mode, implantation or extraction of leads or generators and file closure. The analysis is not linear and does not collect data on follow-up, patient survival, the age of the devices or complications. The card should be completed in the hospital after implantation and a copy sent to the Banco Nacional de Datos de Marcapasos. Information on the European Pacemaker Patient Identification Card can be sent by electronic means, provided that the usual guarantees are met. The Working Group on Cardiac pacing has developed a proprietary database,9 with free access, in an attempt to standardize and automate data collection and processing, although this database has not yet had a significant impact as it is still rarely used.

Sample AnalyzedIn 2011, data were received on the activity conducted in 115 hospitals (Table), representing a 13.8% increase compared with the data collected in 2010. Two nurses with extensive experience in following up pacing device performance conducted data filtering and cleaning using a purpose-built computer application. Regarding certain aspects, data are not available for every year because they were not analyzed at the time; due to changes in software, these data cannot currently be extracted. A total of 13 373 cards were processed, corresponding to pacemaker generator implantations or replacements, representing an 16.4% increase over 2010 and 38.3% of the total number of generators implanted. In total, 220 European Pacemaker Patient Identification Cards were discarded because basic information was missing.

Public and Private Hospitals That Submitted Data to the Spanish Pacemaker Registry in 2011, by Autonomous Region

| Andalusia | Complejo Hospitalario Ntra. Sra. de Valme |

| Complejo Hospitalario Virgen Macarena | |

| Hospital de Benalmádena | |

| Hospital Universitario Ciudad de Jaén | |

| Hospital Costa del Sol | |

| Hospital del Servicio Andaluz de Salud de Jerez de la Frontera | |

| Hospital Infanta Elena | |

| Hospital Juan Ramón Jiménez | |

| Hospital Punta de Europa | |

| Hospital San Cecilio | |

| Hospital Virgen de la Victoria | |

| Aragon | Hospital Miguel Servet |

| Hospital Militar de Zaragoza | |

| Hospital Royo Villanova | |

| Canary Islands | Clínica La Colina |

| Clínica Santa Cruz | |

| Hospital Universitario Ntra. Sra. de la Candelaria | |

| Hospital Dr. Negrín | |

| Hospital General de la Palma | |

| Hospital General de Lanzarote | |

| Hospital Insular | |

| Hospital Universitario de Canarias | |

| Castile and León | Complejo Hospitalario de León |

| Hospital Clínico Universitario de Salamanca | |

| Hospital del Bierzo | |

| Hospital del Río Hortega | |

| Hospital General de Segovia | |

| Hospital General del Instituto Nacional de la Salud de Soria | |

| Hospital General Virgen de La Concha | |

| Hospital General Yagüe | |

| Hospital Universitario de Valladolid | |

| Castile-La Mancha | Hospital General de Ciudad Real |

| Hospital General Virgen de la Luz | |

| Hospital General y Universitario de Guadalajara | |

| Hospital Ntra. Sra. del Prado | |

| Hospital Virgen de la Salud | |

| Catalonia | Hospital Universitari Vall d’Hebron |

| Complejo Hospitalario Parc Taulí | |

| Consorcio Sanitario de Mataró | |

| Hospital Clínic i Provincial Barcelona | |

| Hospital Universitari de Bellvitge | |

| Hospital de Tortosa Virgen de la Cinta | |

| Hospital Arnau de Vilanova | |

| Hospital de Mataró | |

| Hospital de Terrassa | |

| Hospital de Vic | |

| Hospital del Mar | |

| Hospital del Vendrell | |

| Hospital Germans Trias i Pujol | |

| Hospital Joan XXIII de Tarragona | |

| Hospital Mútua de Terrassa | |

| Hospital Sant Joan de Déu | |

| Hospital de Sant Pau i Santa Tecla | |

| Hospital Suroet | |

| Extremadura | Complejo Sanitario Provincial de Plasencia |

| Hospital Comarcal de Zafra | |

| Hospital Comarcal Don Benito-Villanueva | |

| Hospital San Pedro Alcántara | |

| Galicia | Complejo Hospitalario Arquitecto Marcide |

| Complejo Hospitalario Universitario Juan Canalejo | |

| Complejo Hospitalario Xeral-Calde de Lugo | |

| Hospital do Meixoeiro | |

| Hospital Universitario Lucus Augusti | |

| Hospital Montecelo | |

| Balearic Islands | Hospital Mateu Orfila |

| Hospital Universitario Son Espases | |

| Hospital Can Misses de Ibiza | |

| La Rioja | Hospital de San Pedro |

| Community of Madrid | Clínica Ntra. Sra. de América |

| Clínica Quirón | |

| Clínica Ruber Internacional | |

| Clínica San Camilo | |

| Fundación Hospital de Alcorcón | |

| Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre | |

| Hospital Clínico San Carlos | |

| Hospital de Fuenlabrada | |

| Hospital La Zarzuela | |

| Hospital de Móstoles | |

| Hospital de Torrejón | |

| Hospital del Tajo | |

| Hospital General Gregorio Marañón | |

| Hospital Infanta Elena | |

| Hospital Infanta Leonor | |

| Hospital Universitario La Paz | |

| Hospital Príncipe de Asturias | |

| Hospital Puerta de Hierro | |

| Hospital San Rafael | |

| Hospital Sanchinarro | |

| Hospital Severo Ochoa | |

| Hospital Sur de Alcorcón | |

| Hospital Universitario de Getafe | |

| Region of Murcia | Hospital General Santa María del Rosell |

| Hospital General Universitario Morales Meseguer | |

| Hospital Dr. Rafael Méndez | |

| Hospital General Universitario Reina Sofía | |

| Chartered Community of Navarre | Clínica Universitaria de Navarra |

| Hospital de Navarra | |

| Basque Country | Hospital Universitario de Cruces |

| Hospital de Galdakao | |

| Hospital Txagorritxu | |

| Fundación Hospital de Jove | |

| Principality of Asturias | Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias |

| Hospital de Cabueñes | |

| Valencian Community | Clínica Quirón |

| Clínica de Benidorm | |

| Hospital de la Ribera | |

| Hospital de Sagunto | |

| Hospital de San Jaime | |

| Hospital de Vinalopó | |

| Hospital General de Alicante del Servicio Valenciano de Salud | |

| Hospital General Universitario de Elche | |

| Hospital Universitario San Juan de Alicante | |

| Hospital Universitario La Fe | |

| Hospital Vega Baja |

The results are expressed as frequencies, absolute numbers and means; the same structure as that used in previous reports has been retained.

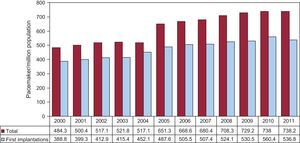

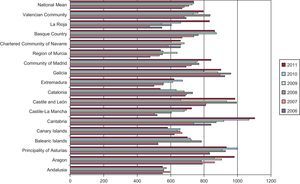

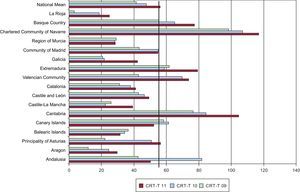

Number of Pacemakers Implanted per Million PopulationAccording to the data provided by the various distributors in 2011, a total of 34 836 pacemaker generators were implanted, including 737 biventricular devices for cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT), without defibrillation capability. These data slightly differ from those submitted to EUCOMED, which reported a total of 35 025 pacemaker generators, 726 of which were biventricular devices without an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator.According to the National Institute of Statistics’ report for 2011, the population was 47 190 000 inhabitants; this figure was based on census data. Thus, according to data from the Banco Nacional de Datos de Marcapasos, 738.2 pacemaker generators were implanted per million population (Figure 1). The distribution of the population by sex was 23 907 000 women and 23 283 000 men; thus, the rate of pacemaker use was 627/million women and 854/million men. As in previous years, the analysis of units implanted per million population by autonomous region showed marked differences.10, 11, 12, 13 There were more than 1000 per million population in Cantabria, followed by Castile-León, Aragon, Principality of Asturias and Galicia with more than 900 (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Number of pacemaker generators and first implantations per million population between 2000 and 2011.

Figure 2. Distribution of pacemaker generators implanted per million population between 2006 and 2011 by autonomous region and the Spanish national average for each year.

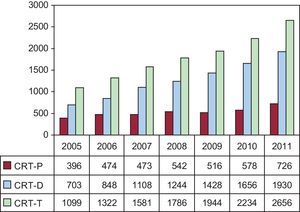

Biventricular PacingThe number of CRT devices used continued to increase steadily, reaching 56.2 units/million population (Figure 3). This increase was due to units with or without an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator, although most had defibrillation capability; low-energy devices were implanted at a rate of 15.3 units/million population. Spain remains one of the European countries with the fewest CRT units implanted per million population.18

Figure 3. Number of cardiac resynchronization devices implanted in the period 2005-2011. CRT-D, biventricular device with defibrillation capability; CRT-P, low-energy biventricular device; CRT-T, total number of cardiac resynchronization devices.

The registry showed that 1.7% of all generators implanted were biventricular units, which were used in 1.4% of first implantations and in 2.5% of replacements.

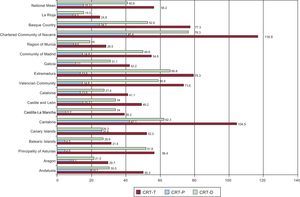

There were also marked differences among regions in their use of CRT devices, which were similar to previous years. The largest number of implantations per million population was performed in the Community of Navarre; both types of devices were used. Navarre was followed by Cantabria and then Extremadura: data on the remaining regions, and for the last 3 years, are shown in Figure 4, Figure 5.

Figure 4. Distribution of cardiac resynchronization devices, with or without defibrillation capability, implanted per million population in 2011 by autonomous region, and the Spanish national average. CRT-D, biventricular device with defibrillation capability; CRT-P, low-energy biventricular device; CRT-T, total number of cardiac resynchronization devices.

Figure 5. Number of cardiac resynchronization devices implanted per million population in the period 2009-2011 by autonomous region, and the Spanish national average. CRT-T, total number of cardiac resynchronization devices. Vertical line indicates the mean for 2011.

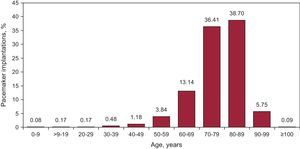

Patient Age and Sex AgeThe mean age of patients who underwent a generator implantation or replacement procedure was 76.9 years: the mean age at first implantation of a cardiac pacing system was 76.7 years and that at first implantation of a generator replacement was 77.5 years.

The highest rate of implantation (38.7%) occurred in the age range 80-89 years, followed by age range 70-79 years (36.4%) and then 60-69 years (13.1%) (Figure 6). Age ranges were similar in generator replacements: 41.9% in the age range 80-89 years, 31.1% in age range 70-79 years and 10.3% in age range 60-69 years.

Figure 6. Distribution of pacemaker implantations performed in 2011 according to age group (10-year intervals).

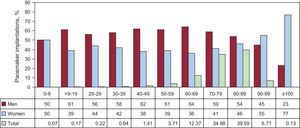

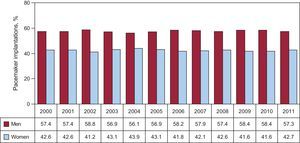

SexIn 2011, as in previous years, there was a sex-associated difference in the mean age at implantation; 76.2 years in men vs 77.9 years in women.

The use of generators was greater in men (57.1%) and in all age ranges, except for patients older than 90 years; in this age group, use was greater in women due to their greater longevity (Figure 7). More procedures were performed in men, both first implantations (57.3%) and replacements (56.5%), which has been the case since records began4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 (Figure 8).

Figure 7. Distribution of patients implanted with pacemakers by age and sex in 2011. Total, percentage of the total number of units implanted (10-year intervals).

Figure 8. Percentages of pacemaker implantations by sex for the period 2000-2011.

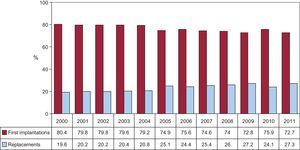

Type of Procedure Pacemaker ImplantationOf all procedures, the percentage of patients who received a first pacemaker was 72.7%; that is, an estimated rate of implantations of 536.8 per million population, representing a decrease of 13.6 units/million population compared with 2010 (Figure 1).

Replacement and Cause of ReplacementReplacements accounted for 27.3% of all the generators used, the highest percentage ever reached (Figure 9).

Figure 9. Percentages of first implantations and replacements for the period 2000-2011.

Generator replacement, including the replacement or implantation of a new lead during the procedure, accounted for 1.5% of all reported activity.

The most common cause of generator replacement was battery depletion due to reaching its end of life (91.3%), followed by infection or erosion of the generator pocket (2.7%; infection, 1.4%), elective (1.8%), premature battery depletion (1.4%), changing the system to improve hemodynamic parameters (0.8%) and generator defects (0.08%). Attention is drawn to the increase in the percentage of premature battery depletion, which, in previous years, did not exceed 0.2%.

Pacing Leads PolarityPacing was performed using bipolar leads in 99.7% of patients. In total, 99.9% of leads implanted in the atrium and 99.8% of those implanted in the right ventricle were of this type.

Of the leads used for epicardial pacing via the coronary sinus, 66% were bipolar, both for left ventricular pacing in cardiac resynchronization and when there were mechanical problems in accessing the right ventricle (tricuspid mechanical valve or congenital malformations).

Only 0.3% of the leads used were monopolar; they are usually chosen when technical difficulties are encountered in the use of the venous route or in cardiac surgical procedures because of their small diameter. The majority were leads for implantation via the coronary sinus (58%), whereas 29% were endocardial leads implanted in the right ventricle; 7% were implanted in the atrium, and the remainder in the epicardium in various cardiac surgery procedures.

Lead Fixation SystemThe retractable active fixation system, forming the distal electrode, was employed in>60% of all implantation procedures; 68% in atrium and 61% in ventricle (Figure 10).

Figure 10. Percentages of total, atrial and ventricular active fixation leads for the period 2000-2011.

An attempt was made to determine whether the age factor had any influence on the choice of the fixation system. We studied 2 age groups with a cutoff point of 80 years and found no significant differences. Active fixation was used in 62.8% of those over 80 years and in 63.5% of those aged less than 80 years.

Extraction and Replacement of Pacing LeadsThe number of lead extractions was reported to the registry; in 2011, 1.5% of the leads implanted were extracted. The most common causes of replacement or extraction were, in order of frequency, infection or ulceration (52.5% of cases), cable breakage or insulation failure (22.5%), displacement or detection problems (12.5%), exit block (5%) and elective (2%).

In 2011, 1.7% of the recorded procedures were for a new electrode lead; 1.5% were procedures associated with generator replacement for hemodynamic improvement or were elective due to deteriorated electrical functions or damage during the surgical procedure. The replacement of a cardiac pacing lead as a specific intervention constituted 0.2% of all procedures.

Symptoms, Etiology and Electrocardiographic Abnormalities Prior to Implantation SymptomsThe clinical characteristics indicating the need for a pacing system were similar to those in previous reports.4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 These were, in descending order: syncope (41.5% of cases), dizziness or signs of heart failure (15.1%), bradycardia (11.1%), asymptomatic or prophylactic (2.4%), chest pain and tachycardia (0.9%), brain dysfunction (0.4%) and resuscitated sudden death from bradyarrhythmia (0.06%).

EtiologyThe most common indication for implantation was unknown etiology (45%), followed by possible fibrosis of the conduction system (39.5%). Of ischemic etiology (6%), 0.2% corresponded to the postinfarction subgroup. These were followed by cardiomyopathy (2.5%; 0.5% of these were hypertrophic) and valve disease (2.9%). The group of iatrogenic-therapeutic etiologies represented 2.2%; of these, 0.5% were secondary to atrioventricular node (AVN) ablation, a figure that has continued to decrease in the last 3 years11, 12, 13 due to new therapies for the treatment and ablation of atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter (AFib/AF). The neurally-mediated group accounted for 1%, slightly higher than in previous years. Among this group, 0.4% corresponded to vasovagal syncope and 0.6% to carotid sinus syndrome. Etiology was congenital in 0.4% of cases.

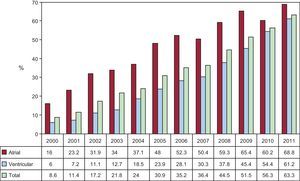

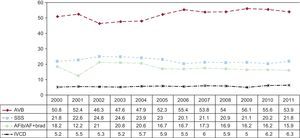

Abnormal Electrocardiographic FindingsThe most common electrocardiographic abnormality before implantation was third-degree atrioventricular block (AVB) in 33.3% of patients. The AVB group comprised 53.9% of patients. Details of all the groups and their progress are shown in Figure 11, Figure 12. No significant changes were observed, despite new indications.3

Figure 11. Percentages of electrocardiographic abnormalities prior to implantation in 2011. AFib/AF+brad, atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter with slow ventricular response; AFib+AVB, atrial fibrillation with atrioventricular block; AT, atrial tachycardia; AVB, atrioventricular block; IVCD, intraventricular conduction disturbance; NC, not codified; SSS, sick sinus syndrome; VT, ventricular tachycardia.

Figure 12. Changes in the incidence of the most common electrocardiographic abnormalities prior to implantation for the period 2000-2011. AFib/AF+brad, atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter with slow ventricular response; AVB, atrioventricular block; IVCD, intraventricular conduction disturbance; SSS, sick sinus syndrome.

Among the various forms of sick sinus syndrome (SSS), excluding AFib or AF with bradycardia, the most common were bradycardia-tachycardia syndrome (35.8%), followed by sinus bradycardia (29.4%), the nonspecific group (14.5%), sinoatrial arrest (11.7%) and exit block (7.6%); interatrial block and chronotropic incompetence reached minimal levels (0.2% and 0.5%, respectively).

Regarding sex, there was a greater incidence of conduction disturbances, AVB and intraventricular conduction disturbances in men, whereas the incidence of SSS was slightly greater in women.9, 10, 11, 12, 13 Thus, the male/female ratio was 1.4 in AVB, 2.5 in intraventricular conduction disturbances and 0.95 in SSS.

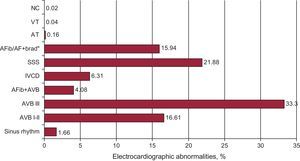

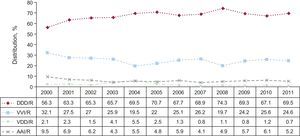

Pacing Modes GeneralOf all generators implanted in 2011, single-chamber atrial pacing (AAI/R) was one of the least used modes (1% of cases), and was used less often in first implantations (0.9%) than in replacements (1.1%).

Single-chamber ventricular pacing (VVI/R) was used in 39.1% of cases (39.7% of first implantations and 37.3% of replacements). As shown by the electrocardiographic indications reported to the registry, there is a significant percentage of patients in whom stimulation in this mode is indicated and who could be stimulated in synchrony with the atrium.1, 2 Its distribution according to the different indications and the factors that may influence the choice are studied in the following sections.

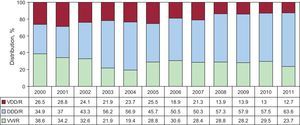

Of all units used, 14.1% involved single-chamber sequential pacing (VDD/R); this was similar to the previous year, with a marked difference between first implantations (11.4%) and replacements (21.1%) (Figure 13).

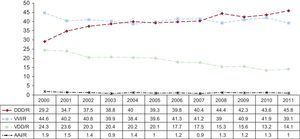

Figure 13. Overall changes in pacing modes for the period 2000-2011.

Dual-chamber sequential pacing (DDD/R) was the most commonly used mode (45.8%) both in first implantations (47.8%) and replacements (40.3%), reaching the highest percentage compared with all previous years.

Overall, atrial-based pacing was 61.1% (Figure 13). In 88.5% of the cases, one or more biosensors were used to vary the cardiac pacing rate.

Biventricular pacing for CRT without implantable cardioverter-defibrillator continued to increase, both in the number of units used (726; 148 more units than in 2010) and units per million population (15.3; an increase of 2.1 units/million population). The greatest increase in the use of CRT was due to units with implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (274 units). Overall, resynchronization devices increased by 422 (56.2 units/million population); this figure is far from the mean reported in European countries19 and from the figures reported to EUCOMED.

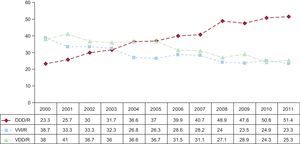

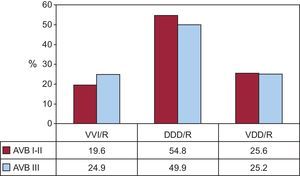

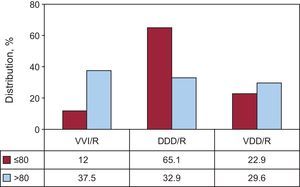

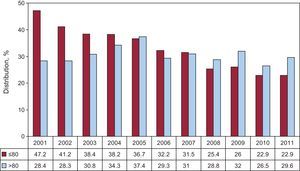

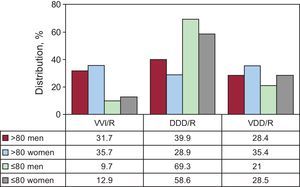

Pacing in Conduction Abnormalities Pacing in Atrioventricular BlockTo accurately evaluate the type of pacing conducted, this study was limited to patients in sinus rhythm and excluded those with atrial arrhythmia in AVB. Thus, we successfully determined the degree of compliance with the most highly recommended pacing modes1, 2 and analyzed potential factors influencing this choice. Synchronized atrial pacing was mainly used (76.7% of cases): 51.4% in DDD/R and 25.3% in VDD/R, with a slight increase in both modes compared with the previous year13 (Figure 14). When comparing the pacing mode according to the degree of block (1 group with first- or second-degree AVB and another with third-degree AVB), it was found that pacing based on atrial synchrony was more commonly used in the first- or second-degree AVB group (80.4%) than in the third-degree AVB group (75.1%). The variations correspond to the greater use of DDD/R mode in the first- or second-degree AVB group, given that use of the VDD/R mode was the same in both groups (25%) (Figure 15). When comparing pacing modes based on atrial synchrony according to the distribution of 2 age ranges using a cutoff of 80 years, a marked difference was observed, reaching 88% in patients aged 80 years or less vs 62.5% in those older than 80. This difference was due to the increased use of DDD/R, since the VDD/R was used more often in the older group (29.6% vs 22.9% in the younger group) (Figure 16). Over time, the use of VDD/R in the group of younger patients has gradually decreased, but has remained steady in the older group (Figure 17). In the same period, the use of DDD/R mode has increased in both age groups, although the percentage is more than double in the younger group (Figure 18). We examined whether sex influenced the choice of pacing mode in these 2 age groups, observing that the use of sequential pacing was somewhat higher in men in both age groups. There was a 4% increase in its use in patients>80 years of age and a 3.2% increase in those<80 years. In both age groups, this was due to the increased use of DDD/R mode, a difference that has already been reported13; the use of VDD/R was more common among women in the same groups (Figure 19). There was still a high percentage of VVI/R pacing in patients with AVB considered to be in sinus rhythm (23.3%). In the last 4 years, the latter figure has ranged between 23% and 24% (Figure 14). This mode was chosen in 12% of patients aged 80 years or less vs 37.5% in those older than 80, a difference that has been maintained over time (Figure 20). It was also used more often in the third-degree AVB group than in the first- or second-degree AVB group (Figure 15) and was used more often in women (Figure 19) in both age groups.

Figure 14. Pacing modes in atrioventricular block, excluding patients with permanent atrial tachyarrhythmia in the period 2000-2011.

Figure 15. Pacing modes according to the degree of atrioventricular block in 2011. AVB, atrioventricular block.

Figure 16. Pacing modes in atrioventricular block by age group (cutoff point 80 years) in 2011.

Figure 17. Changes in the use of VDD/R pacing mode by age (cutoff point 80 years) for the period 2001-2011.

Figure 18. Changes in the use of DDD/R pacing mode by age (cutoff point 80 years) for the period 2001-2011.

Figure 19. Pacing modes in atrioventricular block by age (cutoff point 80 years) and sex in 2011.

Figure 20. Changes in the use of VVI/R pacing mode in atrioventricular block by age (cutoff point 80 years) for the period 2001-2011.

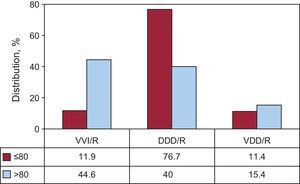

Intraventricular conduction disturbancesThere was little variation in pacing mode in this group. In 2011, there was a noteworthy increase in the pacing mode capable of maintaining atrioventricular synchrony, which reached 76.3% of cases; this improvement was exclusively due to the increased use of DDD/R, which was used in most patients ([63.6%], followed by VVI/R [23.7%]) and VDD/R [12.7%]) (Figure 21). The use of VVI/R was greater in the older group of patients (44.6% vs 11.9% in the younger group) and was shown to be the most common pacing mode in patients older than 80 years. DDD/R was the most commonly used mode in the younger group (76.7% vs 40% in the older group). The use of VDD/R continued to be least affected by age, being employed in 11.4% and 15.4% of patients in the younger and older groups, respectively (Figure 22). Sex had little influence on the use of conventional modes in this group. Thus, VVI/R mode was used in 9.8% of men aged 80 years or younger and in 11.1% of women, with similar percentages in the use of DDD/R. Low-energy CRT devices used for the treatment of ventricular dysfunction associated with dilated cardiomyopathy accounted for 10.7% of all units implanted in this group of electrocardiographic disturbances. As with other devices, there were age- and sex-associated differences; they were used in 17.6% of patients aged 80 years or less and in 4% of patients in the older group. In the younger group they were used more often in women (23.4% vs 13.9% in men).

Figure 21. Pacing modes in intraventricular conduction disturbances for the period 2000-2011.

Figure 22. Pacing modes in intraventricular conduction disturbances by age (cutoff point 80 years).

Pacing in Sick Sinus SyndromeAs in the case of AVB, to assess compliance with the guidelines in the choice of pacing mode,1, 2 we divided our study into 2 parts; 1 dealing with those patients who theoretically are in permanent AFib/AF with bradycardia and the other dealing with patients who are theoretically in sinus rhythm.

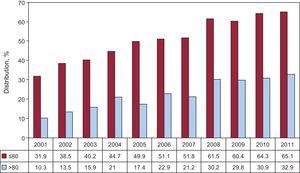

Sinus node pacing in permanent atrial tachycardiaThe pacing mode was expected to be VVI/R in all cases and, in fact, this mode was used in most patients (94.9%). DDD/R units were implanted in 4.6% of patients, as these were patients who had been reverted to or were going to be reverted to sinus rhythm, except for those patients who had been misclassified by group in the European Pacemaker Patient Identification Card. The use of VDD/R mode was minimal (0.5%). This mode is not justified in a patient with SSS except in response to technical problems, a situation we consider extremely unlikely.

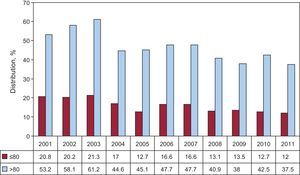

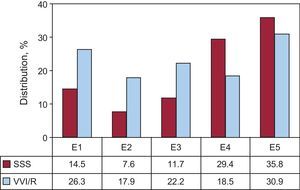

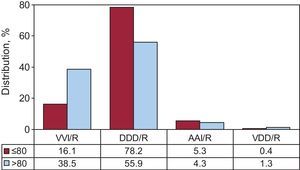

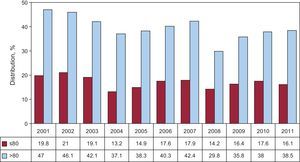

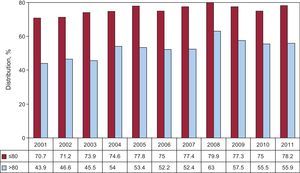

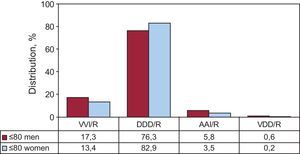

Sinus node pacing in sinus rhythmIn the remaining electrocardiographic abnormalities associated with SSS, in which the atrial rhythm is supposedly stable or intermittent, pacing was performed using devices capable of sensing and pacing the atrium in 75.4% of implantations (reaching 74.4% of all units if replacement is included); these modes are the most widely used for this type of disorder.1, 2 DDD/R mode was used in 69.5% of patients and AAI/R in 5.2%, within the range reported in the last 11 years (Figure 23). Although less suitable for this group of patients, VVI/R mode was chosen in 24.6% and VDD in 0.7%; in fact, neither mode alone is able to produce retrograde conduction symptoms and a higher incidence of AFib involves the potential risk of ventricular dysfunction in the medium term, and so on (Figure 23). We analyzed the type of pacing used in response to the various electrocardiographic signs of SSS to determine whether they could underlie the high rate of VVI/R pacing, excluding the intra-atrial block and chronotropic incompetence groups due to their negligible contribution. The rate of use of VVI/R mode was inappropriate in all of them (ranging from a minimum of 17.9% and a maximum of 30.9%) (Figure 24). In assessing the age factor, in relation to the 2 age groups mentioned, there was a marked difference in the pacing modes used in SSS. Thus, atrial-based modes were used in 83.5% of patients (DDD/R in 78.2% and AAI/R in 5.3%) in the younger group and in 60.2% in the older group (DDD/R in 55.9% and AAI/R in 4.3%) (Figure 25). VVI/R was used in 16.1% of cases in the younger group and in 38.5% in the older group, as in previous analyses (Figure 26). Age continues to be a factor that influences the choice of mode (Figure 27). There was also a small percentage in which VDD was used in both age groups (0.4% and 1.3% in the younger and older groups, respectively). Few sex-associated differences were observed in the choice of pacing mode in SSS; VVI/R was chosen in equal percentages in the older group (38%). However, in the younger group, it was used more often in women (VVI/R in 13.4%) than in men (17.3%) (Figure 28). AAI/R was used more often in women in the older group (5.5%), although overall its use was limited.

Figure 23. Pacing modes in sick sinus syndrome, excluding patients in permanent atrial tachycardia for the period 2000-2011.

Figure 24. Distribution of the incidence of the use of VVI/R in 2011, according to the electrocardiographic code indicated for sick sinus syndrome on the European Pacemaker Patient Identification Card. E1, not specified; E2, exit block; E3, sinoatrial arrest; E4, bradycardia; E5, bradycardia-tachycardia; SSS, sick sinus syndrome.

Figure 25. Pacing modes in sick sinus syndrome by age (cutoff point 80 years) in 2011.

Figure 26. Use of VVI/R pacing mode in sick sinus syndrome by age (cut off point 80 years) for the period 2001-2011.

Figure 27. Changes in the use of DDD/R pacing mode in sick sinus syndrome by age (cutoff point 80 years) for the period 2001-2011.

Figure 28. Pacing modes in sick sinus syndrome in patients aged 80 years or less by sex for the period 2001-2011.

DiscussionAlthough there was a slight increase in the use all generators in 2011 compared with 2010, this was the first year for which data are available in which the number of units used per million population did not increase and is the first time that number of implantations per million population decreased (Figure 1). The cause of these findings remains unknown; according to the National Institute of Statistics’ report, the population has not decreased, and thus a possible reduction in class II indications1, 2 due to the current economic situation cannot be discarded.

In general, more implantation procedures were conducted in the autonomous regions of northern Spain, due to the aging of their populations, as shown by analyzing the percentage of the population>75 years of age.9 International differences were also reported in the rate of implantations recorded in other registries, e.g. in Sweden19 and other countries.20

There was a higher rate of pacemaker implantations in men and at a younger age, which is explained by the greater prevalence of degeneration of the conduction system among them.

The active fixation system was more widely used, both in the atrium and ventricle. There may be various reasons for this, including lead displacement from the right ventricular apex to the outflow tract septum, and from the atrial appendage to the atrial septum; these areas are unsuitable for passive fixation due to the lack of the trabecular structures required. Moreover, active fixation has electrical characteristics similar to those of passive fixation, and lead extraction, if necessary, is usually easier as the lead is isodiametric. The use of active fixation has also proven very useful, or even essential, for the stabilization of the lead in other special settings or adverse hemodynamic and anatomic situations, such as His- or para-Hisian pacing or in the region of the sinus node or in severe tricuspid valve insufficiency, greatly dilated valvular cavities, etc.

The use of AAI/R pacing in SSS remains low, as in other countries,21 possibly because of potential progression to AVB (although the annual incidence is low and generally predictable at follow-up); dual-chamber devices with new pacing modes that effectively prevent unwanted ventricular stimulation are also in use in SSS, but are less efficient systems than AAI/R units, due to their increased cost and potential complications.

The use of VDD/R units (about 4800) per year remained steady, but with a marked difference in use between first implantations (11.4%) and replacements (21.1%), thus confirming their increased use in previous years, accounting for 25% of all generators implanted (1999); however, there is still some interest in this pacing mode for conduction disorders.22

The use of VVI/R pacing in patients in sinus rhythm continues to be high. In AVB, the choice of this mode is influenced by the type of block—less often in first- and second-degree AVB—age (Figure 20) and, to a certain extent, sex (Figure 19). Sex-based differences have also been observed in other studies.23 The use of VVI/R units in SSS is also determined in part by the patient's age, as in AVB, and is probably based on studies that report no effect on survival in elderly patients, in relation to both the class of indication and to the various pacing modes, although quality of life, the incidence of AFib or hospital readmissions for heart failure were not taken into account.24

VVI/R was extensively used in bradycardia-tachycardia syndrome (Figure 24) compared with other signs of SSS. This could be due to a classification problem or confusion regarding this code, which should only include patients with atrial tachyarrhythmia episodes alternating with sinus bradycardia; some patients with permanent AFib episodes and slow-rapid ventricular response episodes may have been mistakenly included, instead of being correctly included in the AFib/AF with bradycardia group.

ConclusionsIn 2011, for the first time, there was a decrease in first conventional pacemaker implantations per million population, although the number of generators used per million population remained the same; however, the number of resynchronization devices with and without defibrillation capability (56.8 units/million population) continued to increase.

Endocardial pacing was performed using bipolar leads and the active fixation system was used in over 60% of cases.

The prevalence of conduction disturbances and the number of pacemaker implantations continued to be greater in men, thus maintaining the trend observed over the years studied.

In relation to all electrocardiographic indications, age, type of AVB and, to a lesser extent, sex were determining factors in the choice of pacing mode. DDD/R pacing was used more in 2011 than in any other year studied.

Conflicts of interestNone declared.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank nurses Pilar Gómez Pérez and Brígida Martínez Noriega and Mr Gonzalo Justes Toha, a specialist in information technology of the Spanish Society of Cardiology, for their continued help in maintaining the registry and its analysis. We woul d also like to thank all the health professionals and the pacemaker manufacturers associated with implantation in Spain who cooperated in providing all the data analyzed.

Corresponding author: Arturo Soria 184, 28043 Madrid, Spain. coma@vitanet.nu