The Working Group on Cardiac Catheterization and Interventional Cardiology presents the yearly report on the data collected for the Spanish registry.

MethodsInstitutions provided their data voluntarily (online) and the information was analyzed by the Working Group's Steering Committee.

ResultsData were provided by 109 hospitals (71 public and 38 private) that mainly treat adults. There were 136 912 diagnostic procedures, 120 441 of which were coronary angiograms, slightly fewer than the year before, with a rate of 2979 diagnostic studies per million population. Percutaneous coronary interventions increased slightly to 65 909 procedures, for a rate of 1434 interventions per million population. Of the 99 110 stents implanted, 62% were drug-eluting stents. In all, 17 125 coronary interventions were carried out during the acute phase of myocardial infarction, 10.5% more than in 2011, representing 25.9% of the total number of coronary interventions. The most frequently performed intervention for adult congenital heart disease was atrial septal defect closure (292 procedures). The use of percutaneous mitral valvuloplasty continued to decline (258 procedures) and percutaneous aortic valve implantations increased by only 10% in 2012.

ConclusionsIn 2012, the only increase in hemodynamic activity occurred in the field of ST-elevation myocardial infarction, and the increasing trend had slowed for percutaneous aortic valve implantation and other procedures affecting structure.

Keywords

This year, in keeping with the custom repeated annually since 1990, one of the most important tasks of the Steering Committee of the Working Group on Cardiac Catheterization and Interventional Cardiology is the collection of data on the activity of the largest possible number of catheterization laboratories for the purpose of preparing the annual registry. In recent years, the data collection has gradually improved1–21 because of online data entry, available in 100% of the centers for the past 2 years, and the data cleaning carried out by members of the steering committee and by working group members. The preliminary data were presented at the annual meeting of this group, which this year was held on June 14 and 15 in A Coruña, in northwestern Spain.

The existence of an annual report of the activity in this area primarily enables the analysis of changes introduced over time, an important aspect that indicates the extent to which percutaneous techniques are being implemented in Spain. The analysis by hospital and by autonomous community establishes a framework for the comparison of the differences in the activity in absolute and relative numbers, as it is corrected for the size of the population in each autonomous community. While we recognize the limitations of voluntary reporting, the information obtained provides us with a view of the true situation in Spain and enables us to relate it to that of other countries and to evaluate the development of interventional cardiology in the different Spanish autonomous communities. Free access to these data helps in understanding the distribution of resources and aids in the evaluation of the different trends in the use of diagnostic and therapeutic procedures.

Although the performance of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), in general, has leveled off in recent years, there have been modifications in some of the variables included in the data collection. The change that stands out from the rest is the marked increase, after two years on the rise, in procedures performed in the setting of acute myocardial infarction (AMI), in which the European initiative, Stent 4 Life,22 may have played a role. The aim of this program is to improve care in myocardial infarction, and Spain is one of its “target” countries.23 Finally, there is evident stagnation in recent years in the number of percutaneous aortic valve implantation procedures observed, both in the number of units implanted and the number of centers at which this technique is carried out.

This article presents the 22nd report on interventional activity in Spain and compiles the data from all the public hospitals and a significant number of private centers.

METHODSWe collected data on the diagnostic and cardiac interventional activities of the majority of Spanish hospitals. Data collection was voluntary and was not audited. In the case of conflicting data or values outside the observed trend in recent years in a given hospital, the researcher responsible for that hospital was consulted for the reassessment of those findings. Data were collected using a standard electronic questionnaire, which was accessed through the website of the Spanish Society of Cardiology Working Group on Cardiac Catheterization and Interventional Cardiology and completed online.24 With the collaboration of Persei Consulting, the working group's steering committee analyzed the data obtained. The results are made public in this article, although a preliminary outline was presented as a slideshow at the working group's annual meeting.

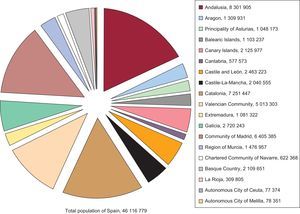

Calculations involving the population of Spain and of each of its autonomous communities were based on the size of the population estimated by the Spanish National Institute of Statistics up to December 31, 2012, as published on its website.25 The Spanish population was estimated at 46 116 779 inhabitants (Fig. 1). As in 2010 and 2011, the procedures per million population for the country as a whole were calculated on the basis of the overall population. In previous years, these rates were calculated from averages in the different provinces where interventional cardiology was carried out, rather than on the overall population. Although the differences may be small compared to previous years, the final result is closer to reality. This year, in contrast to previous years, the true number of coronary arteriograms per million population was calculated, taking into account the total number of diagnostic coronary arteriograms.

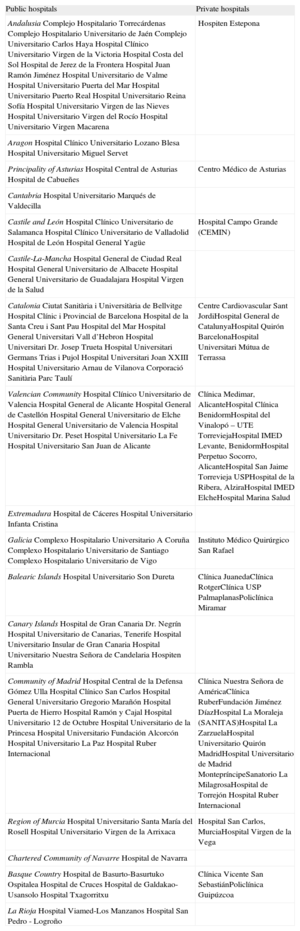

RESULTSInfrastructure and ResourcesA total of 109 hospitals that performed interventional procedures in adults participated in the present registry (1 more than the preceding year); of these, 14 (2 more than in 2011) also carry out these techniques in pediatric patients (Appendix). In all, 98.6% of the public hospitals (71 of the 72 public centers) and 25.7% of private hospitals (38 of 148 private centers) provided their data. This represents nearly all of the hospitals in which interventional procedures are performed in Spain. There were 177 cardiac catheterization laboratories, 132 (75%) of which were located in public hospitals; 29 centers had 2 laboratories, and 12 had 3 or more. A 24-h emergency team was available in 71% of the hospitals and cardiac surgery was performed in 64%.

With regard to personnel, the 109 hospitals reported a total of 430 physicians (351 of them accredited) who performed interventional procedures in the year 2012. There were 2.47 physicians per laboratory in the public hospitals (328 physicians), and 2.32 per laboratory in the private centers. There were 576 registered nurses and 93 radiology technicians, an overall average of 3.82 per public hospital and 3.66 per private hospital.

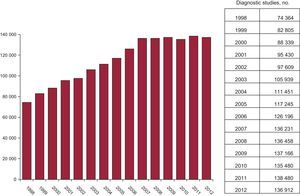

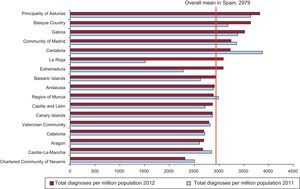

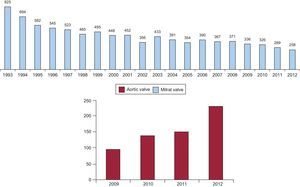

Diagnostic ProceduresIn 2012, 136912 diagnostic tests were carried out, representing a 1.13% decrease from the previous year. Of those tests, 123746 were coronary angiograms, 2.6% fewer than in 2011. Of these procedures, 28.5% were performed in women and 28.7% in patients over 75 years of age, figures that remain very stable from one year to the next. The Spanish national average for diagnostic tests was 2979 procedures per million population, slightly lower than that of previous years (3008 procedures per million population in 2011), when this was always reported as coronary angiograms per million population. Counting only the coronary angiograms, this figure is actually 2621 procedures per million population in 2012, much lower than the European estimates as far back as 2006.26Figure 2 shows the changes in the numbers of diagnostic procedures since 1998.

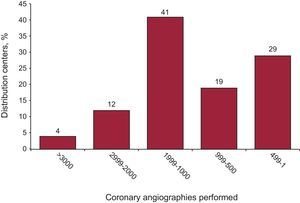

With respect to the diagnostic activity by centers, 57 performed more than 1000 coronary angiograms (3 more than in 2011), and only 16 undertook more than 2000 (4 centers more than in the preceding year) (Fig. 3). An average of 1256 diagnostic procedures were carried out per hospital, a figure very similar to that reported in recent registries.18–21 It should be pointed out that 59.76% of the diagnostic procedures involved radial artery access, representing a significant increase from 2011 (51.74%).

Figure 4 shows the distribution of diagnostic tests per million population according to autonomous community. The average per million population was 2979, slightly lower than that recorded in 2011 (3008 diagnostic studies per million population).

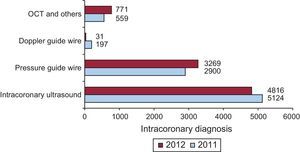

With respect to intracoronary diagnostic techniques, the use of intravascular ultrasound declined for the second consecutive year, with a cumulative decrease of 21% over the past two years, although it remains the most widely employed technique. The use of the pressure guide wire continues to increase steadily, although not at the same pace, as the increment was 22% in 2011 and 12.7% in 2012. Optical coherence tomography also exhibited a considerable 37.9% growth in 2012. Figure 5 shows the changes in the rates of utilization of the different intracoronary diagnostic techniques with respect to 2011.

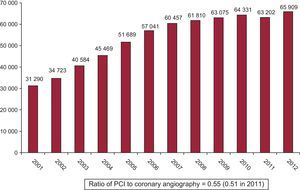

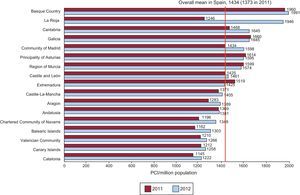

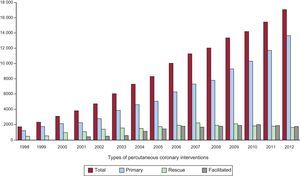

Percutaneous Coronary InterventionIn contrast to the previous registry, where a decrease in PCI procedures was recorded for the first time, the number of these procedures increased by 2707 (1.04%) in 2012, for a total of 65909. The changes in the use of PCI over the years is shown in Figure 6. In 2012, the number of PCI per million population was 1434 (vs 1373 in 2011). All the hospitals that performed diagnostic procedures also performed PCI.

The ratio of PCI to coronary angiography (Fig. 6) was 0.55 (0.51 in 2011). The number of procedures performed for multivessel disease in 2012 decreased by 1% with respect to the previous year and corresponds to 24.8% of all PCI; there were no differences in the number of ad hoc procedures carried out during diagnosis (74%).

As in 2011, the PCI distribution according to sex and age group showed a rate of 21.5% in women and of 24.8% in patients over 75 years of age of either sex. Restenosis was reported in 4.9% of the cases (5% in 2011 and 5.3% in 2010), and a trend toward a reduction in its use has been detected.

Although the number of procedures involving unprotected left main coronary artery is similar to 2011 (1810 interventions vs 1828, respectively), representing 2.75% of all PCI (2.89% in 2011), there has been a modest decrease since 2010 (2271 procedures and 3.53% of all PCI).

With respect to the use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIb inhibitors and bivalirudin as adjuvant drug therapy, the continuous and marked decrease in the administration of these agents is worthy of note; they were utilized in only 10952 procedures, 16.6% of all PCI (0.9% less than in the preceding year).

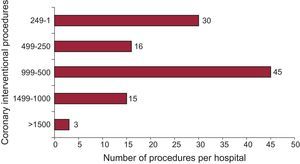

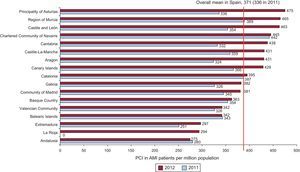

The distribution of the 1434 PCI per million population according to autonomous community is shown in Figure 7. With regard to the distribution by hospital (Fig. 8), 46 hospitals (42%) performed fewer than 500 PCI in 2012, compared to 50 centers in 2011; this category includes a large number of the private hospitals. There were 18 high-volume centers (>1000 procedures), 1 more than in 2010 and 2011.

There was a clear difference in the use of intracoronary diagnostic techniques (intravascular ultrasound and pressure guide wire), which are mainly employed to evaluate the severity of intermediate lesions or the results of the intervention. The use of intravascular ultrasound continued to decline, to 7.3% of the interventions (0.8% less than in 2011). In contrast, the use of the pressure guide wire rose to 4.9%. Once again, there was an upsurge in the use of radial access to perform PCI, which increased by 4.6%, reaching a rate of 60.15% and surpassing femoral access in this intervention.

StentsStents were implanted in 83.66% of all PCI (5.34% less than in 2011), totaling 99110 units in 55140 PCI in 2012, 4409 more units than in 2011 and 1261 fewer than in 2010. The ratio of stents per patient continued to be 1.5 (1.56 in 2010 and 1.63 in 2009). The use of drug-eluting stents remained nearly unchanged at 61.82%, corresponding to 61274 units. Whether one type of stent or the other, or both, were employed depended on the characteristics of the patient and the target lesions; in 2012, drug-eluting stents alone were placed in 35% of the procedures, the same proportion as in 2011 and very similar to that reported for 2009 and 2010 (but nearly 20% fewer than in 2008).

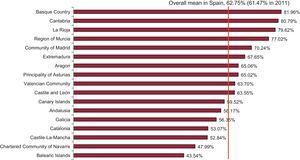

The use of drug-eluting stents continued to vary considerably from one autonomous community to another and, once again, the rate of utilization was highest in the Basque Country (81.96%), whereas the lowest rate (43.54%) was recorded in the Balearic Islands (Fig. 9).

The first implantations of the so-called “scaffolds”, or fully biodegradable coronary devices, were documented in 375 procedures. For the first time, we decided to analyze the use of intracoronary self-expanding devices (97 procedures) and those employed specifically in the treatment of bifurcations (267 procedures).

Other Devices and Procedures Employed in Percutaneous Coronary InterventionsThe use of rotational atherectomy has declined slightly, with 1194 cases compared to 1225 in 2011. It seems to have leveled off since 2010. There are no records of the performance of directional atherectomy or intracoronary brachytherapy. There was an increase in the utilization of coronary laser, with 14 cases (6 in 2011). The cutting balloon somewhat recovered its former level of use, with 1982 cases (1916 in 2011 and 2092 in 2010), as have special balloons with protrusions or guide wires, with 571 cases compared to 492 in 2011. Drug-eluting balloons were used in 1675 cases, for an increase of 9% with respect to 2011. With regard to thrombectomy catheters, the spectacular increase in their use continued, with 9041 cases in 2012, 10% more than in 2011. The figures indicate that these devices were employed in 66% of primary PCI procedures.

Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in Acute Myocardial InfarctionThe 17125 PCI procedures performed in AMI patients represented a 10.5% increase over 2011, in which there was a 9.4% increase over 2010, and correspond to 25.9% of all PCI. Of all these procedures, 56% (n=9626) involved radial access, compared to 49% in 2011.

Within the scope of PCI procedures carried out during the acute phase of AMI, primary angioplasty continued to increase; it was the only modality to do so, at rates that have gone from 9334 in 2009 to 10339 in 2010, 11766 in 2011, and 13690 in 2012. Primary PCI procedures represented 20.7% of all angioplasties and 80% of all the PCI procedures performed in association with myocardial infarction; the use of facilitated angioplasty remained the same, whereas the performance of rescue angioplasty continued to decline somewhat (Fig. 10).

The distribution of PCI in AMI cases throughout Spain was similar to that of previous years; the best data were provided by those autonomous communities that had established a program of continuous care in AMI (Fig. 11).

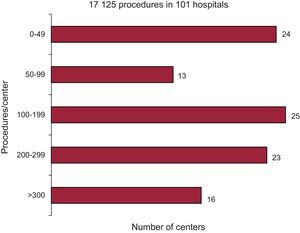

With regard to the number of procedures per center, 39 performed more than 200 PCI in AMI patients in 2012 (12 more hospitals than in 2010), whereas 24 carried out fewer than 50 (16 fewer centers than in 2010) (Fig. 12).

Noncoronary Interventions in AdultsFor the first time since this registry began to be published, the use of aortic valvuloplasty (258 cases) surpassed that of mitral valvuloplasty (254 cases), undoubtedly owing to the new surge in aortic valve replacement from the increasing use of transcatheter aortic valve implantation (Fig. 13). The growth in this percutaneous technique slowed, but continued to increase appreciably, with 426 procedures in 2009, 655 in 2010, 770 in 2011, and 845 in 2012. Of the latter group, 425 interventions were performed with self-expanding prostheses and 420 with balloon-expandable prostheses.

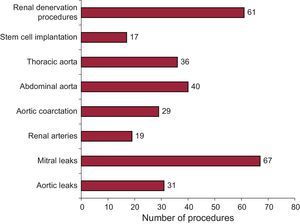

The treatment of adult congenital heart disease has remained stable over the last 4 years with regard to atrial septal defect closure (292 cases), whereas patent foramen ovale closure was performed in only 188 patients (265 in 2010 and 195 in 2011). Other noncoronary procedures included the treatment of 29 cases of aortic coarctation and 98 cases of paravalvular leak, and the performance of renal denervation in 61 cases (Fig. 14).

DISCUSSIONThe data collected on PCI activity in 2012 show that usage has clearly leveled off for most percutaneous techniques, both diagnostic and interventional. A sustained increase was observed only in the area of primary angioplasty, probably related to the implementation and stabilization of treatment protocols in different hospitals and autonomous communities. While the upward trend in transcatheter aortic valve implantation has continued, it slowed markedly in comparison with recent years.

With respect to European standards, Spain continues to rank below average in the performance of many techniques, but this is especially striking in the case of transcatheter aortic valve implantation, which has leveled off at rates per patient that are markedly lower than in the rest of Europe.27 We consider that this last finding should be analyzed in the context of the current Spanish and European economic situation, which may have an impact on recently introduced, costly techniques.

Diagnostic activity has decreased slightly and, perhaps more striking, if we analyze the true rate of coronary angiographies per million population (until now, the number of diagnostic cardiac catheterizations had been used to represent the number of coronary angiographies), it is 2621 coronary angiographies per million. This is clearly far below that of the most recently published European data referring to 2005, which sets this rate at 4030 coronary angiographies per million population,28 or the data presented for 2009 at the 2011 EuroPCR congress, in which the mean was estimated to be over 5500 coronary angiographies per million population.29

With respect to interventional activity, the slight increase recorded during the years prior to 2011 (when there was a slight decline) has again been observed, but this is due to the sustained growth in the number of interventional procedures in AMI which, in 2012, was more than 10% higher than that of 2011. There is a persistent perception that the cases of “complex” percutaneous coronary revascularization have clearly leveled off since 2009, as have the number of stents implanted, the ratio of stents per patient, and the number of special devices used in cases of this type, such as those designed for rotational atherectomy or the cutting balloon. The publication of the FREEDOM trial in diabetics30 and the long-term results of the SYNTAX trial31 that were published in 201332 have probably constituted a setback to this treatment in patients with multivessel disease and complex anatomies, especially in diabetics. There has also been a greater use of the pressure guide wire, probably for decision making as recommended by the FAME study,33 which can reduce both the number of PCI procedures and the numbers of lesions treated and stents. The implementation of long stents (over 30 mm) in cardiac catheterization laboratories may also have contributed to maintaining a low ratio of stents per patient. In contrast, it is difficult to understand the stagnation in the percutaneous treatment of unprotected left main coronary artery, which has been shown in recent studies to have highly promising results.34,35

Despite the increase in emergency interventional procedures in myocardial infarction in Spain, we continue to be far from the rest of Europe in terms of intervention rates. Our rate of 1434 PCI procedures per million population was far below the latest published European data reporting 1601 PCI per million population in 200528 or the nearly 2000 per million in 2009.29

Perhaps one of the most encouraging findings from the registries in recent years, especially 2012, is the increase in the number of primary PCI procedures, which is clearly related to the implementation of the Stent 4 Life initiative of the European Society of Cardiology.22 In fact, the recent article by Kristensen et al.36 cites Spain as one of the countries that responded well to the initiative. Nevertheless, if there are an estimated 45000 AMI a year in Spain,37,38 primary PCI would have been performed in less than 40% of the AMI patients, whereas the Stent 4 Life initiative proposes a target of primary PCI in 70% of AMI cases.22 We should point out that emergency interventional procedures involve radial access, in more than 50% of AMI patients in Spain.

The increase in the use of transcatheter aortic valve implantation was much less marked, failing to reach a 10% growth, compared to much greater increases in previous years.

CONCLUSIONSThe data for 2012 continued to show a leveling off or a slight decrease in the upward trend in both diagnostic and therapeutic procedures. The progressive increase in the use of angioplasty in the setting of AMI, particularly primary PCI, continued, due to both the incorporation of new autonomous communities into primary PCI programs and the marked increase in the number of procedures performed in certain centers. The Stent 4 Life program, the priority objective of both the European Society of Cardiology and the Spanish Society of Cardiology, as well as our own working group, seems to be helping to increase the awareness of both the administration and of physicians as a group of the need to improve care in myocardial infarction in Spain as a way of increasing both the life expectancy and quality of life of patients with coronary artery disease.

Differences between autonomous communities persist in coronary interventional procedures in general and, in particular, those performed in myocardial infarction.

We wish to emphasize that, although the use of transcatheter aortic valve implantation increased by 10%, the rate remains far below those reported for Europe.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTNone declared.

The Steering Committee of the Working Group on Cardiac Catheterization and Interventional Cardiology would like to thank the directors and staff of Spain's catheterization laboratories, as well as those responsible for data collection, for contributing their work to make this registry possible.

| Public hospitals | Private hospitals |

| AndalusiaComplejo Hospitalario TorrecárdenasComplejo Hospitalario Universitario de JaénComplejo Universitario Carlos HayaHospital Clínico Universitario Virgen de la VictoriaHospital Costa del SolHospital de Jerez de la FronteraHospital Juan Ramón JiménezHospital Universitario de ValmeHospital Universitario Puerta del MarHospital Universitario Puerto RealHospital Universitario Reina SofíaHospital Universitario Virgen de las NievesHospital Universitario Virgen del RocíoHospital Universitario Virgen Macarena | Hospiten Estepona |

| AragonHospital Clínico Universitario Lozano BlesaHospital Universitario Miguel Servet | |

| Principality of AsturiasHospital Central de AsturiasHospital de Cabueñes | Centro Médico de Asturias |

| CantabriaHospital Universitario Marqués de Valdecilla | |

| Castile and LeónHospital Clínico Universitario de SalamancaHospital Clínico Universitario de ValladolidHospital de LeónHospital General Yagüe | Hospital Campo Grande (CEMIN) |

| Castile-La-ManchaHospital General de Ciudad RealHospital General Universitario de AlbaceteHospital General Universitario de GuadalajaraHospital Virgen de la Salud | |

| CataloniaCiutat Sanitària i Universitària de BellvitgeHospital Clínic i Provincial de BarcelonaHospital de la Santa Creu i Sant PauHospital del MarHospital General Universitari Vall d’HebronHospital Universitari Dr. Josep TruetaHospital Universitari Germans Trias i PujolHospital Universitari Joan XXIIIHospital Universitario Arnau de VilanovaCorporació Sanitària Parc Taulí | Centre Cardiovascular Sant JordiHospital General de CatalunyaHospital Quirón BarcelonaHospital Universitari Mútua de Terrassa |

| Valencian CommunityHospital Clínico Universitario de ValenciaHospital General de AlicanteHospital General de CastellónHospital General Universitario de ElcheHospital General Universitario de ValenciaHospital Universitario Dr. PesetHospital Universitario La FeHospital Universitario San Juan de Alicante | Clínica Medimar, AlicanteHospital Clínica BenidormHospital del Vinalopó – UTE TorreviejaHospital IMED Levante, BenidormHospital Perpetuo Socorro, AlicanteHospital San Jaime Torrevieja USPHospital de la Ribera, AlziraHospital IMED ElcheHospital Marina Salud |

| ExtremaduraHospital de CáceresHospital Universitario Infanta Cristina | |

| GaliciaComplexo Hospitalario Universitario A CoruñaComplexo Hospitalario Universitario de SantiagoComplexo Hospitalario Universitario de Vigo | Instituto Médico Quirúrgico San Rafael |

| Balearic IslandsHospital Universitario Son Dureta | Clínica JuanedaClínica RotgerClínica USP PalmaplanasPoliclínica Miramar |

| Canary IslandsHospital de Gran Canaria Dr. NegrínHospital Universitario de Canarias, TenerifeHospital Universitario Insular de Gran CanariaHospital Universitario Nuestra Señora de CandelariaHospiten Rambla | |

| Community of MadridHospital Central de la Defensa Gómez UllaHospital Clínico San CarlosHospital General Universitario Gregorio MarañónHospital Puerta de HierroHospital Ramón y CajalHospital Universitario 12 de OctubreHospital Universitario de la PrincesaHospital Universitario Fundación AlcorcónHospital Universitario La PazHospital Ruber Internacional | Clínica Nuestra Señora de AméricaClínica RuberFundación Jiménez DíazHospital La Moraleja (SANITAS)Hospital La ZarzuelaHospital Universitario Quirón MadridHospital Universitario de Madrid MontepríncipeSanatorio La MilagrosaHospital de Torrejón Hospital Ruber Internacional |

| Region of MurciaHospital Universitario Santa María del RosellHospital Universitario Virgen de la Arrixaca | Hospital San Carlos, MurciaHospital Virgen de la Vega |

| Chartered Community of NavarreHospital de Navarra | |

| Basque CountryHospital de Basurto-Basurtuko OspitaleaHospital de CrucesHospital de Galdakao-UsansoloHospital Txagorritxu | Clínica Vicente San SebastiánPoliclínica Guipúzcoa |

| La RiojaHospital Viamed-Los ManzanosHospital San Pedro - Logroño |