Heart transplant (HT) remains the best therapeutic option for patients with advanced heart failure (HF). The allocation criteria aim to guarantee equitable access to HT and prioritize patients with a worse clinical status. To review the HT allocation criteria, the Heart Failure Association of the Spanish Society of Cardiology (HFA-SEC), the Spanish Society of Cardiovascular and Endovascular Surgery (SECCE) and the National Transplant Organization (ONT), organized a consensus conference involving adult and pediatric cardiologists, adult and pediatric cardiac surgeons, transplant coordinators from all over Spain, and physicians and nurses from the ONT. The aims of the consensus conference were as follows: a) to analyze the organization and management of patients with advanced HF and cardiogenic shock in Spain; b) to critically review heart allocation and priority criteria in other transplant organizations; c) to analyze the outcomes of patients listed and transplanted before and after the modification of the heart allocation criteria in 2017; and d) to propose new heart allocation criteria in Spain after an analysis of the available evidence and multidisciplinary discussion. In this article, by the HFA-SEC, SECCE and the ONT we present the results of the analysis performed in the consensus conference and the rationale for the new heart allocation criteria in Spain.

Keywords

Heart transplant (HTx) remains the best therapeutic option for patients with advanced heart failure (HF) who fail to respond to conventional medical therapy.1,2 However, HTx availability is limited by the number of donors, which averages about 300 per year in Spain.3 Accordingly, allocation criteria are required to guarantee equitable access to HTx, prioritizing patients with worse clinical status while avoiding futility.

On June 27, 2022, a consensus conference was held in Madrid, organized by the Heart Failure Association of the Spanish Society of Cardiology (HFA-SEC), the Spanish Society of Cardiovascular and Endovascular Surgery (SECCE), and the Spanish National Transplant Organization (ONT). This conference gathered all HTx teams in Spain, as well as transplant coordinators and members of the National Transplant Organization. The aims were to review HTx outcomes in Spain after the 2017 modification of the allocation criteria and to suggest new criteria. Working groups were created to propose new allocation criteria, which were presented in a subsequent meeting in February 2023 to all active HTx teams in Spain. After discussion, the new heart allocation criteria were finally approved. In March 2023, the implementation of these criteria in Spain was ratified by the Permanent Transplant Commission of the Interterritorial Council of the Spanish National Health System. In the current HFA-SEC/ONT/SECCE document, we present the analyses performed, summarize the deliberations held, and explain the new heart allocation criteria for Spain.

ORGANIZATION OF CARE FOR ADVANCED HEART FAILURE IN SPAIN: HEART TRANSPLANTATION AND CARDIOGENIC SHOCK. “HUB AND SPOKE” MODELThe complex management of HF explains the need for HF units, which permit systematic clinical management via a structure that coordinates the actions of the diverse entities and personnel involved in patient care.1 According to the level of each hospital, there are 3 types of HF units, linked by agile referral pathways: community, specialized, and advanced.4

Patients with HF must be regularly followed up to detect disease progression. When advanced HF criteria are met, patients must be referred to an advanced center for HF treatment with HTx or durable ventricular assist device (dVAD) availability.2 In the “Hub and Spoke” care organizational model, the central hub (a hospital center with HTx/dVAD) is closely linked to its spoke centers (referral hospitals). This model provides these patients with excellent care, as long as there is fluid 2-way communication and specific referral protocols that consider the geographical characteristics and resources of each center. Figure 1 shows the HTx and dVAD centers for adults and children in Spain.

Geographical distribution of heart transplant centers and those with durable ventricular assist device (dVAD) availability in Spain. Overall, 18 centers have a heart transplant and adult dVAD program, 10 centers have an adult dVAD program, and 6 centers have a heart transplant and pediatric dVAD program.

The most severe form of HF is cardiogenic shock. The process can be halted by the emergency use of short-term mechanical circulatory support (MCS), which can allow recovery from the multiorgan damage. Cardiogenic shock is an example of a condition that benefits from an organized network facilitating the rapid identification, initial treatment, transfer, and subsequent definitive treatment of these patients.

In Spain, the use of MCS in patients with cardiogenic shock is widespread, and some centers have shock teams and even organized and autonomous “shock code” strategies. However, official recognition and planning are generally poor in this setting. The preferential attention received by this topic in the recently published Cardiovascular Health Strategy of the Spanish National Health System,5 together with initiatives of autonomous communities and the scientific community, may be a starting point for change.6

REVIEW OF HEART ALLOCATION CRITERIA IN OTHER ORGANIZATIONS: COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS WITH SPAINTable 1 summarizes the heart allocation criteria applied by various transplant organizations.

Heart allocation criteria in different transplant organizations

| Spain (2022 criteria) | Eurotransplant | France | United Kingdom | United States |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urgency status 0 (national)• Total ST-VAD support, without multiorgan failure• VA-ECMO or partial ST-VAD support, more than 2 days after implantation and less than 7 days on the waiting list, extendable to 10 days if the patient is extubated• Patients with malfunctioning dVAD due to mechanical dysfunction or thrombosisPediatric patients: any type of circulatory support (including VA-ECMO)Urgency status 1 (regional)• Patients with a properly functioning external dVAD• Patients with a malfunctioning implanted dVAD due to driveline infection, gastrointestinal bleeding, or severe right ventricular failure• Hyperimmunized patients responding to desensitization therapyPediatric patients:• Patients requiring intravenous inotropic support• Fontan circulation with severe protein-losing enteropathy• Restrictive cardiomyopathy with a pulmonary vascular resistance index ≥ 6 WU/m2Regional priority (after urgency status 1)• Patients with a cPRA ≥ 50% and possibility of virtual crossmatch | International priority• Signs of hypoperfusion with inotropic dependence or temporary MCS• Intractable ventricular arrhythmias• Amyloidosis or restrictive cardiomyopathy• Severe congenital heart disease• Severe primary graft failure• dVAD with complications: dVAD dysfunction, thromboembolism, intractable bleeding, aortic regurgitation, systemic infection, chronic right heart failureNational priority (own national criteria) | Individual score including:1. Recipient risk score based on VA-ECMO presence and duration of support, natriuretic peptides, glomerular filtration rate, and bilirubin2. Exception (additional points):• Complications from dVAD (thrombosis, bleeding, infection, dysfunction)• Arrhythmic storm• TAH and BVS without complications• Contraindication to MCS3. Transplant risk score: based on 7 recipient variables (age, indication, previous cardiac surgery, diabetes mellitus, mechanical ventilation, glomerular filtration rate, and bilirubin) and 2 donor variables (age and sex). This criterion is Yes/No and means that a heart is not offered if the mortality risk is ≥ 50%4. The total score is adjusted to the predicted travel time | Superurgent:• VA-ECMO• Temporary MCS• Accepted by a panel of experts and 1 of the following: IABP, imminent risk of death and/or complications without possibility of MCS implantation, pediatric patients on VA-ECMOUrgent:• Inotropic agent/IABP dependency• TAH or dVAD with RV failure and inotropic agent dependency or recurrent infection or thrombosis• High risk of death or irreversible complications• Refractory arrhythmia• Not candidate for MCS or inotropic agents and 1 MOF criterion*Pediatric patients:• Short-term MCS or Berlin Heart• dVAD with complications• >15kg with high-dose inotropic agents• <15kg, ventilated with inotropic agents• Exception | Status 1• VA-ECMO• Unstable surgically implanted biventricular MCS• Ventricular arrhythmia with MCSStatus 2• Nondischargeable MCS, surgically implanted, not endovascular• IABP• Ventricular arrhythmias without MCS• MCS dysfunction• Endovascular MCS• TAH, BVS, univentricular support in patients with a single ventricleStatus 3• Dischargeable dVAD, less than 30 days• High-dose inotropic agents with hemodynamic monitoring• VA-ECMO after 7 days, percutaneous ventricular support or IABP> 14 days• dVAD with a complication: infection, hemolysis, thrombosis, RV failure, mucosal bleeding, aortic regurgitationStatus 4• Dischargeable dVAD, after 30 days• Inotropic agents without hemodynamic monitoring• Retransplantation• Congenital heart disease• Intractable angina• Hypertrophic or restrictive cardiomyopathy/amyloidosisStatus 5On the waiting list for another organ in the same hospital |

BVS, biventricular support; cPRA, Calculated Panel Reactive Antibody; dVAD, durable ventricular assist device; IABP, intra-aortic balloon pump; MCS, mechanical circulatory support; MOF, multiorgan failure; RV, right ventricle; ST-VAD, short-term ventricular assist device; TAH, total artificial heart; VA-ECMO, venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; WU, Wood units.

Most organizations prioritize patients based on need for short-term MCS, whether venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VA-ECMO) or univentricular or biventricular assistance. Spain7 and the United Kingdom8,9 do not differentiate between univentricular and biventricular MCS while the United States10 prioritizes patients on biventricular MCS. France prioritizes patients according to a recipient risk score comprising analytical parameters of HF severity and multiorgan failure parameters but the greatest weight is given to VA-ECMO use.11

The next prioritization level includes dVAD with complications. Depending on the organization, driveline infection of the device has the same level of urgency as thrombosis/pump dysfunction, such as in the United Kingdom8,9 and United States.10 In contrast, infection is of lower priority in Spain. In France, any dVAD complication can add a score exception to the risk score.11 Biventricular MCS without complications can also add to this score exception. Intra-aortic balloon pumps and inotrope use as a definition of a severe status requiring prioritization was discontinued in Spain in 2017 3 but was maintained in Eurotransplant,12 the United Kingdom (after expert committee assessment),8 and the United States (priority 3, of 5 levels).10

Because patients who undergo transplantation while on VA-ECMO have higher mortality,13,14 several countries limit the number of days in which patients on VA-ECMO have national priority. The French system additionally includes a score predicting the risk of mortality after HTx based on recipient and donor variables and blocks heart offers if the predicted 1-year mortality risk after HTx is ≥ 50%.11

France, Eurotransplant, and the United States also prioritize patients with arrhythmic storm or those who cannot receive MCS due to restrictive cardiomyopathy/amyloidosis.10–12 Spain and Canada are the only countries to prioritize sensitized patients.13

Most transplant systems prioritize pediatric patients due to a lower probability of transplant vs adults and due to the ethical principles of distributive justice.7,8,12

ANALYSIS OF PATIENTS ON THE HEART TRANSPLANT WAITING LIST AND OF DONORS IN SPAIN BEFORE AND AFTER THE 2017 CRITERIA MODIFICATIONIn 2017, the priority listing criteria for HTx were modified in Spain. The main changes comprised removal of intra-aortic balloon pump3,7,14,16 as a priority listing criterion and the limiting of the time in status 0 to a maximum of 7 to 10 days for patients on VA-ECMO or Impella (Abiomed, United States). Until 2017, patients with dVAD were prioritized in status 1 and moved to status 0 with the development of any type of complication. From 2017, patients with a properly functioning implantable dVAD ceased to have priority and the degree of prioritization differed by the type of complication (table 1).

MethodologyA retrospective observational study was performed using data from the Spanish National Transplant Organization (April 2012 to March 2022), the National Transplant Registry (October 2013 to December 2020), and the ASIS-TxC Registry (January 2010 to December 2020) and by comparing the period before modification of the criteria (period 1 [before June 2017]) with the subsequent period (period 2 [after July 2017]). All registries adhered to the recommendations of the Declaration of Helsinki and were approved by local ethics committees, and all patients consented to the anonymized use of their data for research purposes by being placed on the waiting list. Quantitative variables are expressed as median [interquartile range] and categorical variables as No. (%). According to the normality of the data, differences between periods were analyzed with a chi-square test or Fisher exact test for categorical variables or with a t test or Mann-Whitney U-test for quantitative variables. Survival curves were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method and were compared using a log-rank test. The hazard ratio (HR) for mortality according to period was determined using a Cox regression model adjusted by variables associated with mortality at P <.10 in univariate analysis.

Impact on urgent heart transplantationIn total, 46.2% of patients were urgent transplant recipients in period 1 vs 37.1% in period 2 (P <.01). Particularly in period 2, a major decrease was recorded in urgency status 1 patients (46.2% vs 12.8%; P <.001) due to the exclusion of intra-aortic balloon pump and properly functioning implanted dVADs from this urgency status.16

HTx probability in urgency status 0 increased significantly in period 2 (79% vs 85%; P=.01). In addition, in period 2, time on the urgent waiting list fell (median, 23 days vs 11 days; P <.001), as well as waiting list mortality and urgent waiting list exclusion.

In period 2, 70% of patients on the urgent list received some type of MCS vs 40% in period 1 (P <.001). VA-ECMO and the CentriMag (Abbott, United States) were the most commonly used MCS devices in urgency status 0. Moreover, period 2 exhibited lower use of VA-ECMO (28.4% vs 24.2%) and significantly higher use of the CentriMag (6.6% vs 31.5%) and Impella (1% vs 10%).14 The incremental use of dVADs in period 2 led to an increase in urgent inclusions due to dysfunction or associated complications (0.4% in period 1 vs 2.8% in period 2). Although the difference was significant, this indication represented just 0.9% of all urgent transplants.

Recipients’ baseline characteristics were similar in the 2 periods. The data revealed lower prevalences of infection and mechanical ventilation and a higher prevalence of cardiac surgery before transplant in recipients in period 2 (table 1 of the supplementary data).

The median age of donors was 47 years, without differences between periods. Period 2 showed a higher percentage of donors with cardiorespiratory arrest and higher weight. In addition, the percentages of female donors and male recipient-female donor mismatching were lower in period 2, although the ischemia time was longer. The percentage of donors older than 60 years was lower for urgent transplants vs elective transplants in period 2 (5.3% vs 10%; P=.018), whereas the percentage of men was higher for urgent vs elective transplants in period 2 (74.5% vs 54.5%; P <.001) (tables 2-4 of the supplementary data).

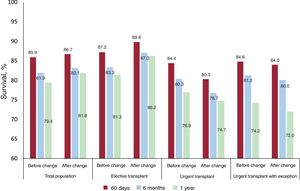

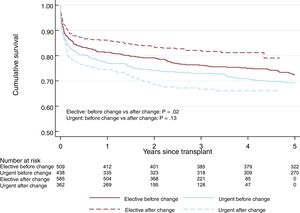

No significant differences were observed in 1-year survival after urgent HTx between the 2 periods: 76.4% in period 1 vs 74.7% in period 2 (P=.13) (figure 1). This tendency for shorter survival in period 2 was not significant in the multivariate-adjusted comparison (HR=1.14; 95% confidence interval [95%CI], 0.84-1.56). Table 5 of the supplementary data shows the variables included in the multivariate analysis. The incidence of primary graft failure was not significantly different between the 2 periods (21.2% in period 1 vs 18.9% in period 2).

Impact on elective heart transplantationThe percentage of patients undergoing an elective transplant was significantly higher in period 2 than in period 1 (79% vs 73%; P <.001), as was transplant probability (50% vs 42%; P <.001). Waiting list time for elective HTx did not vary between the 2 periods. However, waiting list mortality, waiting list exclusion, and expanded mortality (encompassing deaths and exclusions due to clinical deterioration) were significantly worse in period 2 (2.9% vs 4.4% [P <.02]; 10.2% vs 14.4% [P <.001]; and 5.7% vs 9.7% [P <.001]).

Recipient age was similar in the 2 periods. A higher proportion of women was seen in period 2. This increment was probably related to the significant increases in period 2 in congenital heart diseases and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy as underlying heart diseases (table 6 of the supplementary data).

In relation to the donors used for elective transplantation, no significant differences were detected in age, sex, or weight. Ischemia times and male recipient-female donor mismatching were lower in period 2 (tables 7-9 of the supplementary data).

Elective HTx survival was better in period 2 and was 86.2% at 1 year after the HTx (figure 2 and figure 3). This trend for longer survival in elective HTx was not statistically significant after multivariate adjustment (HR=0.82; 95%CI, 0.62-1.08). Table 10 of the supplementary data shows the variables included in the multivariate analysis.

We additionally analyzed LEVO-T registry data, which included patients on the elective HTx waiting list with and without intermittent levosimendan therapy (504 patients in period 1 and 511 patients in period 2) between January 2015 and September 2020.17 Patients who died on the waiting list or were excluded from the list fell from 8.6% in period 1 to 5.6% in period 2 (P=.07). The percentage of patients who ultimately underwent transplantation was similar in the 2 periods (91.3% in period 1 and 93.0% in period 2), with a highly significant decrease in waiting list time from 230.8 days to 142.3 days (P <.001). These differences were observed for both elective transplants (from 241.0 days to 145.7 days) and urgent transplants (from 197.1 days to 119.5 days). Survival times from time of waiting list inclusion and after transplantation were similar in the 2 study periods.

Impact on patients receiving long-term mechanical circulatory supportThe REGALAD registry includes all patients implanted with a dVAD in 25 Spanish hospitals from 2007 to December 2021.18 The increased use of dVADs in Spain in recent years is due to technical advances and improvements in dVAD outcomes,19 more than the influence of the changes to urgency criteria. Regarding the 133 devices implanted prior to 2017, the 170 devices implanted between 2017 and 2021 were associated with an increase in the mean patient age (from 56 to 61 years; P <.01) and a significant increase in continuous-flow devices (from 4% to 94%; P <.001), left-sided devices (from 86% to 97%; P <.01), and devices implanted as destination therapy (from 19% to 41%; P <.01) or as a bridge to candidacy (from 36% to 45%; P <.01). In the entire series, 114 patients underwent transplantation while on a dVAD—83 were urgent and 31 were elective—and 1-year survival was 75%, with no significant differences between the 2 periods (table 11 of the supplementary data). A comparison of periods 1 and 2 revealed an increase in elective HTx in patients with a dVAD (8% vs 51%) (figure 1 of the supplementary data). Although there were no differences in mortality between urgent and elective HTx in patients with a dVAD in period 1, survival after elective HTx was better in period 2 (figure 2 of the supplementary data).

Impact on pediatric patients undergoing heart transplantationIn pediatric patients (age <18 years at time of HTx), a nonsignificant increase was seen in urgent transplantation in period 2 (62.2% vs 74.5%). In period 2, more female patients underwent transplantation and more patients with dilated cardiomyopathy. There were no changes in the use of MCS before HTx: it was mainly applied in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy (59.7%) rather than congenital cardiomyopathy (25.7%). In addition, no significant differences were seen in post-HTx survival between the 2 periods.

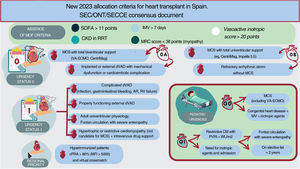

NEW ALLOCATION CRITERIA FOR HEART TRANSPLANT ESTABLISHED IN SPAIN IN 2023The new allocation criteria are summarized in figure 4 and table 2 and are detailed in full in document 2 of the supplementary data.

Central illustration. AR, aortic regurgitation; CKD, chronic kidney disease; cPRA, calculated panel reactive antibody; dVAD, durable ventricular assist device; IMV, invasive mechanical ventilation; MCS, mechanical circulatory support; MFI, median fluorescence intensity; MOF, multiorgan failure; MRC, medical research council; MV, mechanical ventilation; ONT, National Transplant Organization; PVRI, pulmonary vascular resistance index; RRT, renal replacement therapy; SEC, Spanish Society of Cardiology; SECCE, Spanish Society of Cardiovascular and Endovascular Surgery; SOFA, sepsis-related organ failure assessment; VA-ECMO, venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

New allocation criteria for heart transplant in Spain (2023)

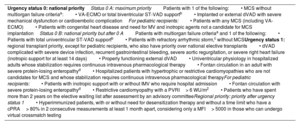

| Urgency status 0: national priorityStatus 0 A: maximum priorityPatients with 1 of the following:• MCS without multiorgan failure criteriaa:• VA-ECMO or total biventricular ST-VAD supportb• Implanted or external dVAD with severe mechanical dysfunction or cardioembolic complicationFor pediatric recipients:• Patients with any MCS (including VA-ECMO)• Patients with congenital heart disease and need for MV and inotropic agents not a candidate for MCS implantationStatus 0 B: national priority but after 0 APatients with multiorgan failure criteriaa and 1 of the following:• Patients with total univentricular ST-VAD supportb• Patients with refractory arrhythmic storm,c without MCSUrgency status 1: regional transplant priority, except for pediatric recipients, who also have priority over national elective transplants• dVAD complicated with severe device infection, recurrent gastrointestinal bleeding, severe aortic regurgitation, or severe right heart failure (inotropic support for at least 14 days)• Properly functioning external dVAD• Univentricular physiology in hospitalized adults whose stabilization requires continuous intravenous pharmacological therapy• Fontan circulation in an adult with severe protein-losing enteropathyd• Hospitalized patients with hypertrophic or restrictive cardiomyopathies who are not candidates for MCS and whose stabilization requires continuous intravenous pharmacological therapyFor pediatric recipients:• Patients with inotropic support with or without IMV who require hospital admission• Fontan circulation with severe protein-losing enteropathyd• Restrictive cardiomyopathy with a PVRI> 6 WU/m2• Patients who have spent more than 2 years on the elective waiting list after assessment by an advisory committeeRegional priority: priority after urgency status 1• Hyperimmunized patients, with or without need for desensitization therapy and without a time limit who have a cPRA> 80% in 2 consecutive measurements at least 1 month apart, considering only a MFI> 5000 in those who can undergo virtual crossmatch testing |

cPRA, Calculated Panel Reactive Antibody; dVAD, durable ventricular assist device; MCS, mechanical circulatory support; MFI, mean fluorescence intensity; MV, mechanical ventilation; PVRI, pulmonary vascular resistance index; ST-VAD, short-term ventricular assist device; VA-ECMO, venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

Including CentriMag with or without membrane oxygenation and Impella 5.0, Impella 5.5, Impella RP, and Impella CP in patients with a body surface area <1.70 m2.

One of the main novelties of the new criteria is the subdivision of urgency status 0 into 0 A and 0 B based on whether the short-term MCS is biventricular or univentricular. To avoid futile HTx, it has been agreed to temporarily exclude from the waiting list patients in multiorgan failure due to its association with worse outcomes after HTx.13 In addition, because patients on VA-ECMO have a short window of opportunity before complications develop, their waiting time in urgent status 0 has been limited. All of these factors lead us to the following actions:

- 1.

Definition of multiorgan failure criteria that cannot be present at the time of patient inclusion or during waiting list stay. Multiorgan failure is defined as the presence of at least 1 of the following:

- a)

A Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment score> 11 points for 48hours. This cutoff point was chosen because a score of 12 or more points in the first 48hours of admission in a critical care unit predicts a risk of mortality exceeding 49%.20

- b)

Renal failure requiring renal replacement therapy, except when the patient is a candidate for heart-kidney transplantation, based on worse outcomes after HTx in these patients.13 Notably, ultrafiltration for fluid removal is not considered renal replacement therapy.

- c)

Patients who have been receiving invasive mechanical ventilation for a maximum of 7 consecutive days, based on worse outcomes in transplant recipients who are on mechanical ventilation.13,21 The sole exception is patients with arrhythmic storm.

- d)

Patients who have been receiving mechanical ventilation for more than 5 days and, after extubation, have critical myopathy with a Medical Research Council muscle strength score <36. Although the literature indicates that values <55 are associated with worse prognosis,22 we decided to apply a lower cutoff point to avoid being too restrictive, due to the lack of data in the HTx setting.

- e)

Patients on MCS and with a need for high-dose vasoactive drugs, defined by a Vasoactive Inotropic Score> 20 because this cutoff point has been shown to predict worse prognosis, particularly in patients on MCS. This criterion is not applied to patients not on MCS but it must be remembered that this cutoff point is also associated with worse prognosis in general after HTx.23

- a)

- 2.

Prioritization as urgency status 0 A patients with total biventricular short-term MCS, including VA-ECMO, over those with total univentricular short-term MCS, who would be prioritized as urgency status 0 B. The devices providing total support are listed in document 2 of the supplementary data. It must be noted that the Impella CP (Abiomed) is only considered to provide total support in patients with a low body surface area. Unlike previously, no specific time limit is set for VA-ECMO because we consider that stricter criteria in the absence of multiorgan failure would limit the inclusion of patients with an elevated risk of mortality after HTx, independently of time on MCS.

- 3.

Additional prioritization of patients with refractory arrhythmic storm defined as persistent despite optimal treatment for at least 4 days and without MCS. For listing as urgency status 0 B, all of the following requirements must be met:

- a)

Deep sedation defined by a Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale <–3 or requiring invasive mechanical ventilation.

- b)

Optimal electrophysiological treatment that includes ineffective ablation or nonablatable arrhythmia.

- c)

Absence of multiorgan failure criteria.

- d)

Absence of arrhythmias secondary to specific causes with possibility of recovery.

- a)

- 4.

Continued consideration of patients with a dVAD with severe mechanical dysfunction or thromboembolic complications in urgency status 0 A.

This urgency status prioritizes patients ahead of elective HTx candidates within the corresponding geographical area for organ transplant allocation. This priority grading includes patients with specific congenital heart diseases, as in pediatric HTx, and newly includes hypertrophic or restrictive cardiomyopathies not requiring MCS but dependent on continuous intravenous infusion because these patients already need a biventricular MCS and preferably VA-ECMO, which has been associated with worse prognosis.14

REGIONAL PRIORITYWith the aim of simplifying the prioritization of sensitized patients, we decided to increase the Calculated Panel Reactive Antibody cutoff to ≥ 80%, without the need for desensitization therapy (similar to the Canadian criteria).15 Because the prioritization of hyperimmunized patients is not based on the clinical severity of the patient but on the difficulty of obtaining an appropriate donor, it was decided that these patients would be prioritized, within the region, after patients in urgency status 1.

PEDIATRIC HEART TRANSPLANTATIONAs a consequence of the prioritization of patients with MCS, the evidence shows a progressive increase in patients undergoing urgent HTx while on MCS (currently 33.5%) and a significant decrease in such patients undergoing elective transplantation (table 12 of the supplementary data). This trend would be unsurprising if the patients on MCS (urgency status 0) were all patients with worse clinical status. However, most patients with MCS have dilated cardiomyopathy (66.9%) rather than congenital heart disease (23.3%): just 42.3% of these patients can avail of VA-ECMO, which has very short durability and highly elevated mortality (figure 3 of the supplementary data and table 13 of the supplementary data). Consequently, 27.7% of patients with dilated cardiomyopathy undergo urgent transplantation on a MCS; this figure is 11.9% for those with congenital heart disease (P <.001).

For this reason, we propose prioritization in urgency status 0 A patients with congenital heart disease experiencing clinical deterioration (judged by need for mechanical ventilation and inotropic support) who do not respond to stabilization via implantation of a ventricular assist system.

PRIORITIZATION PROCEDUREIn all cases, for prioritization on the HTx waiting list, a clinical report must be submitted with a correctly completed waiting list inclusion form (document 2 of the supplementary data). For patients who do not meet the established urgency criteria but who should be prioritized according to transplant team judgment, the National Transplant Organization will, on a case-by-case basis, consult the advisory committee to assess the request and reach a resolution (document 2 of the supplementary data).

DISCUSSIONThe 2017 modification of the allocation criteria was accompanied by a significant decrease in the number of patients placed on the urgent waiting list and in the percentage of patients receiving an urgent transplant due to a temporary restriction in the length of VA-ECMO or Impella use and the removal of intra-aortic balloon pump as a priority listing criterion. This has resulted in a more effective resolution of urgent transplants that are largely represented by urgency status 0, with a reduction in urgent waiting list times. The type of MCS at transplantation (less VA-ECMO and more CentriMag), the optimization of the recipients’ clinical status, and the short waiting times in our system have permitted acceptable survival, despite the severe clinical status of patients who undergo urgent transplants.

The fall in urgent transplants after 2017 has been accompanied by an increased probability of elective transplantation, without changes in the elective transplant waiting times and with a tendency for improved survival after HTx. This tendency could be due to improved patient selection, shorter ischemia times, and less male recipient-female donor mismatching. The second period may also have been influenced by greater use of the HeartMate 3 continuous-flow dVAD (Abbott) as a bridge to HTx or candidacy,18 due to its better durability and lower rate of associated complications.19 Together, these factors mean that patients undergo HTx in better conditions.

The new allocation criteria prioritize more severe patients, defined as those with biventricular MCS rather than univentricular support, similar to the United States.10 To avoid futility, we have defined strict criteria for multiorgan failure that, once met, exclude patients from the urgent waiting list, similar to the risk score used in France.11 The time criteria for MCS has been removed, which could penalize patients who did not develop complications with the initial MCS. This avoids the possibility of a new surgery being conducted for the patient to remain in urgency status 0. Given the excellent durability of current dVADs,19 it seem reasonable to prioritize these patients only when certain complications develop, as in most of our neighboring countries.8,9,11,12,19

With these criteria, the following are now considered urgent listing conditions: refractory arrhythmic storm without MCS, hyperimmunization, congenital heart disease, and hypertrophic or restrictive cardiomyopathy. The latter are also prioritized in other HTx systems.10–12 The reason for this prioritization is that these patients cannot undergo inotropic therapy and, for both these patients and those with congenital heart disease, the MCS is restricted to VA-ECMO, which is independently associated with higher post-HTx mortality.14

Within the pediatric priority listing criteria, an urgent priority listing is established for those with congenital heart disease with a severe clinical status not requiring MCS to promote early transplantation and a better clinical status at transplant. The 2018 implementation of ABO-incompatible HTx in Spain has significantly reduced waiting list times for the youngest recipients.

LimitationsThe comparative analysis of the periods before and after the 2017 changes to the allocation criteria included data from different registries, which means that there are some differences in the total population and inclusion/follow-up times.

CONCLUSIONHTx remains the best therapeutic option for patients with advanced HF in Spain. After the 2017 revision of the allocation criteria, the evidence shows a reduction in urgent transplants and shorter urgent waiting list times but no improvements in post-HTx mortality. An increase was seen in elective HTx, with a tendency for improved survival in this group of patients. The new allocation criteria for 2023 attempt to prioritize patients with more severe clinical status while improving post-HTx survival and to facilitate HTx access in patients not needing a dVAD. The clinical outcomes of these new criteria must be assessed 3 years after their implementation.

FUNDINGAbbott sponsored the catering and travel of the researchers to Madrid for the consensus conference on June 27, 2022, but the scientific program of the conference and this manuscript were independently designed and written by the authors.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONSJ. González-Costello, A. Pérez-Blanco, J. Delgado-Jiménez, and B. Domínguez-Gil conceived and designed the manuscript. All authors participated in the data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation. F. González-Vílchez, S. Mirabet, E. Sandoval, J. Cuenca-Castillo, M. Camino, J. Segovia-Cubero, J.C. Sánchez-Salado, E. Pérez de la Sota, L. Almenar-Bonet, M. Farrero, E. Zataraín, M.D. García-Cosío, I. Garrido, E. Barge-Caballero, M. Gómez-Bueno, J. de Juan Bagudá, N. Manito-Lorite, A. López-Granados, L. García-Guereta, T. Blasco-Peiró, J.A. Sarralde-Aguayo, M. Sobrino-Márquez, L. de la Fuente-Galán, and M.G. Crespo-Leiro contributed to the manuscript drafting. The remaining authors performed a critical revision. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript and take responsibility for all of its aspects. Document 3 of the supplementary data includes a list of attendees of the consensus conference of June 27, 2022.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTJ. González-Costello has received fees for educational presentations and consultancy work from Abbott and Chiesi and grants for travel to conferences from Abbott and is an ex-president of the Heart Failure Association of the Spanish Society of Cardiology. E. Sandoval has received fees for consultancy work from Abbott and for educational presentations from Medtronic and Edwards. E. Zataraín has received fees for consultancy work from AstraZeneca and Bayer and grants for travel to conferences from Bayer and is a member of the Committee for the Defense and Promotion of the International Cardio-Oncology Society. M.G. Crespo-Leiro has receiving grants for travel to conferences from Abbott. L. Doñate has received fees for expert testimony from Palex and grants for travel to conferences from Palex and Edwards. J. Hernández-Monfort has received fees for consultancy work and for educational presentations from Abbott and Abiomed. A. García-Quintana has received fees for presentations from Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Bayer, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Vifor, and Daichii Sankyo and grants for travel to conferences from Novartis, and fees for consultancy work from Bayer, Novartis, Daichii Sankyo, and Novo Nordisk and is ex-president of the Canarian Society of Cardiology. The remaining authors have no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rec.2023.11.001