The objective of the OFRECE study was to estimate the prevalence of stable angina in Spain. This prevalence is currently unknown, due to a lack of recent studies and to changes in the epidemiology and treatment of ischemic heart disease.

MethodsThis cross-sectional study involved a representative sample of the Spanish population aged 40 years or older, obtained via 2-stage random sampling: in the first stage, primary care physicians were randomly selected from each Spanish province, whereas in the second stage 20 people were selected from the population assigned to each physician. The prevalence was weighted by age, sex, and geographical area. Participants were classified as having angina if they met the “definite angina” criteria of the Rose questionnaire and as having confirmed angina if the angina was confirmed by a cardiologist or if they had a history of acute ischemic heart disease or revascularization.

ResultsOf the 11 831 people invited to participate, 8378 (71%) were analyzed (mean age, 59.2 years). The weighted prevalence of definite angina (Rose) was 2.6% (95% confidence interval, 2.1%-3.1%) and was higher in women (2.9%) than in men (2.2%), whereas that of confirmed angina was 1.4% (95% confidence interval, 1.0%-1.8%), without differences between men (1.5%) and women (1.3%). The prevalence of definite angina (Rose) increased with age (0.7% in patients aged 40 to 49 years and 7.1% in those aged 70 years or older), history of cardiovascular disease, and cardiovascular risk factors, except smoking.

ConclusionsThe prevalence of definite angina (Rose) in the Spanish population aged 40 years or older was 2.6%, whereas that of confirmed angina was 1.4%. Both prevalences increased with age, cardiovascular risk factors, and cardiovascular history.

Keywords

In recent decades, significant advances have been made in the understanding of the pathophysiology and pharmacological and interventional treatment of coronary artery disease. At the same time, developed countries have launched preventive interventions against cardiovascular risk factors (CVRFs). Both aspects should have contributed to improve the epidemiological data and prognosis of ischemic heart disease.1–3 Although the prevalence of stable angina in Spain has been evaluated in various population studies, none has been recent. These studies estimated a 2% to 4% prevalence of stable angina, with marked regional variations.4 In the United States, an analysis of studies of acute coronary syndrome (ACS) led to an estimate of 16.5 million people with angina (prevalence of 5.3%) via analysis of studies of ACS.5 Nonetheless, advances in preventive intervention and treatment should have decreased the incidence of ischemic heart disease and increased the number of asymptomatic patients after diagnosis.6,7 Therefore, the prevalence of stable angina has probably changed.

In Spain, the prevalence of stable angina has been examined in only 2 population studies (PANES8 and REGICOR9). The PANES study showed a high prevalence of stable angina (7.5%), attributable in part to the study methodology, whereas the REGICOR study reported a prevalence of only 3.5%. The latter study was performed in a specific area of Girona province and in individuals aged between 24 and 75 years. The main limitation of both studies is that they were performed more than 15 years ago and probably no longer reflect the current situation. Thus, a new evaluation of the prevalence of stable angina in Spain seems pertinent. The main objective of the OFRECE10 study was to estimate the prevalence of atrial fibrillation and stable angina in the Spanish population aged 40 years or older, stratified by age (decades) and sex. This article provides information on the current prevalence of stable angina.

METHODSDesign and DefinitionsThe present cross-sectional study of the Spanish population aged 40 years or older was conducted in primary care (PC). The OFRECE study was approved by the Ethics Committee for Clinical Research of Hospital Universitario de Basurto. The main characteristics of its methodology have already been described.10 Briefly, to obtain a representative sample of the Spanish population, for each Spanish province one hospital and health care area (2 in Madrid and Barcelona) and one cardiologist were selected. The cardiologists acted as study coordinators. Ultimately, 46 provinces and 47 hospitals and cardiologists participated. Four provinces and the second center in Madrid were excluded or failed to participate due to various logistic problems. The next step was multistage random sampling. All PC physicians of the area assigned to each hospital were identified and 10 physicians from each area were selected by simple random sampling. In total, the participating hospitals contained 7959 PC physicians attending 340 883 persons older than 39 years. Of the 769 physicians invited to participate, 425 (55.2%) accepted (Figure 1). Of the population aged 40 years or older assigned to each participating PC physician, a sufficient number were selected by simple random sampling to obtain 20 individuals per physician. At this stage, 76% of those invited agreed to participate (n=8400). All participants provided informed consent. The study was carried out from March 2010 through October 2012. Only 22 participants had to be withdrawn from the final analysis of the prevalence of angina (4 due to missing key information and 18 for failing to fully complete the form on angina, which included the Rose questionnaire). The final sample for the analysis of the prevalence of stable angina was 8378 people (Figure 1).

Flow diagram of participation in the OFRECE study relative to angina analysis. aMadrid participated with only 1 of the 2 previously selected centers. bBarcelona (2 hospitals participated). cReasons for losses: unreachable after attempted postal and/or telephone contact; participant refusal: lack of interest (personal or work reasons preventing attendance at the center to participate in the study); unknown: unspecified cause.

All participants were examined by their PC physician who, with the clinical history and other information provided by the patient, completed questionnaires/forms on CVRFs and medical history, atrial fibrillation, and angina (Rose questionnaire).8,11,12 The Rose questionnaire has 7 test-type questions (Appendix 2 of the supplementary material) with 4 to 7 possible answers. Based on the answers, the patients were classified as: a) without angina; b) having definite angina; c) having possible angina, and d) having atypical angina. Patients were only considered to have angina if they met all “definite angina” criteria. In addition, all participants underwent an electrocardiogram and measurements of their weight, height, and blood pressure (2 measurements, in accordance with World Health Organization guidelines). If the existence of an unknown heart disease was suspected during a clinic visit, an appointment was made for the patient with the coordinating cardiologist and the patient was informed of the need for a full diagnostic workup. The various clinical variables were defined according to the guidelines of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association for atrial fibrillation13 and are described in the first publication from this study.10 Participants were given a diagnosis of previous ischemic heart disease only if it was documented that they had already had myocardial infarction, unstable angina, or revascularization.

Two definitions of angina were used: a) definite angina: when participants were classified as having definite angina by the Rose questionnaire, and b) confirmed angina: when participants with “definite angina” (Rose questionnaire) also had one of the following conditions:

- •

Diagnosis confirmed by a cardiologist after complete evaluation.

- •

Previous diagnosis of documented myocardial infarction, unstable confirmed angina, or coronary revascularization.

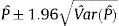

The sampling process gave each individual in the population a different probability of being selected. Therefore, a weight was assigned to each participant in the final sample to reflect the number of people of the Spanish population from the same age group, sex, and geographical area represented by this participant.14 Weighting was performed in 2 phases. As the study used a 2-stage sampling design, the first phase was to calculate the weight of the design as the inverse of the selection probability for each individual in each stage of the sampling process. For the first stage (physician selection), the selection probability for each province was calculated using the number of PC physicians in the province. For the second stage (participant selection), the denominator was the number of people aged ≥ 40 years assigned to each physician. In the second phase, reweighting was performed to adjust the sample distribution to that of the population according to age and sex, variables related to the outcome but not considered in the sampling process. This reweighting applied the procedure proposed by Deville and Särndal15 using the calibrate instruction of the Stata v10.1 statistical software package (all analyses were performed using this program). To adjust or calibrate the sample, the population used was the municipal census of 2011. In the case of definite and confirmed angina, the weighted prevalences were calculated by age and sex according to the population distribution and 95% confidence intervals (95%CIs). In the methodology used to calculate the confidence intervals of the prevalences, the variance of the proportion estimator was approximated using Taylor series linearization and the 95%CI was then obtained using the expression:

To identify cardiovascular risk factors and angina-related history, age- and sex-adjusted odds ratios (ORs) were estimated using logistic regression modeling. Subsequently, a multivariate model was constructed to include those factors with P < .1 in the univariate analysis.

RESULTSThe mean age of the 8378 participants in the analysis of angina prevalence in the OFRECE study was 59.2 (95%CI, 58.6-59.7) years; 52.6% were women. The general characteristics of the studied population are shown in Table 1, as well as comparisons between patients with definite (Rose questionnaire) or confirmed angina and the rest of the population. The overall population showed high prevalences of risk factors and certain antecedents. Notably, 45.3% of the population was hypertensive, 4.9% had a history of ischemc heart disease, and 3.0% had a diagnosis of heart failure. There were high frequencies of obesity (34%) and overweight (42%).

General Characteristics (Demographic Data, Cardiovascular Risk Factors, and History) of the Study Population and of the Patients With Definite Angina (Rose Questionnaire) and Confirmed Angina. Comparison Between Patients With Angina (Definite or Confirmed) and the Rest of the Population

| All | Definite angina (Rose) | Confirmed angina | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | P | Yes | No | P | ||

| Participants, No. | 8378 | 210 | 8168 | 117 | 8261 | ||

| Sex, % | |||||||

| Men | 47.4 | 40.4 | 47.6 | .156 | 53.0 | 45.7 | .448 |

| Women | 52.6 | 59.6 | 52.4 | 47.0 | 54.3 | ||

| Age group, % | |||||||

| 40-49 y | 31.2 | 8.4 | 31.8 | < .001 | 6.4 | 31.6 | < .001 |

| 50-59 y | 24.5 | 16.3 | 24.7 | 18.5 | 24.6 | ||

| 60-69 y | 19.3 | 13.1 | 19.5 | 10.7 | 19.4 | ||

| 70-79 y | 14.9 | 40.7 | 14.2 | 46.9 | 14.5 | ||

| ≥ 80 y | 10.1 | 21.5 | 9.8 | 17.6 | 10.0 | ||

| Cardiovascular risk factors | |||||||

| Obesity, % | 33.7 | 49.7 | 33.3 | < .001 | 47.1 | 33.5 | .035 |

| Overweight, % | 42.0 | 36.1 | 42.2 | .159 | 37.5 | 42.1 | .491 |

| BMI, mean | 28.40 | 30.09 | 28.40 | .011 | 29.80 | 28.40 | < .001 |

| Central obesity, % | 55.6 | 75.0 | 55.1 | < .001 | 76.9 | 55.3 | < .001 |

| Hypercholesterolemia, % | 25.3 | 63.9 | 24.3 | < .001 | 75.6 | 24.6 | < .001 |

| Diabetes mellitus, % | 12.2 | 29.3 | 11.7 | < .001 | 28.9 | 11.9 | < .001 |

| Current smoker, % | 22.2 | 8.5 | 22.6 | < .001 | 11.0 | 22.4 | .012 |

| Hypertension, % | 45.3 | 71.4 | 44.6 | < .001 | 83.5 | 44.8 | < .001 |

| SBP (mmHg), mean | 130.90 | 131.74 | 130.90 | .834 | 131.80 | 130.90 | .564 |

| DBP (mmHg), mean | 77.80 | 76.24 | 77.90 | .012 | 74.20 | 77.9 | .101 |

| History, % | |||||||

| Stroke | 3.8 | 9.5 | 3.6 | < .001 | 14.0 | 3.6 | < .001 |

| Peripheral artery disease | 2.4 | 8.9 | 2.2 | < .001 | 11.3 | 2.2 | < .001 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 6.3 | 14.8 | 6.0 | < .001 | 17.7 | 6.1 | < .001 |

| Thyroid disease | 6.9 | 9.6 | 6.8 | .218 | 8.6 | 6.9 | .581 |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 2.9 | 19.8 | 2.5 | < .001 | 37.4 | 2.5 | < .001 |

| Unstable angina | 2.5 | 33.1 | 1.7 | < .001 | 62.6 | 1.7 | < .001 |

| Surgical revascularization | 1.1 | 15.1 | 0.7 | < .001 | 28.5 | 0.7 | < .001 |

| Percutaneous revascularization | 1.9 | 15.9 | 1.5 | < .001 | 30.0 | 1.5 | < .001 |

| Pacemaker implantation | 0.7 | 2.8 | 0.7 | < .001 | 3.5 | 0.7 | < .001 |

| ICD implantation | 0.7 | 2.8 | 0.7 | < .001 | 3.5 | 0.7 | < .001 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 4.9 | 45.8 | 3.8 | < .001 | 86.4 | 3.8 | < .001 |

| Previous diagnosis of HF | 3.0 | 20.9 | 2.5 | < .001 | 23.2 | 2.7 | < .001 |

95%CI, 95% confidence interval; BMI, body mass index; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; HF, heart failure; ICD, implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

In the studied population, 210 participants met the Rose questionnaire criteria for definite angina, giving an adjusted prevalence of 2.6% (95%CI, 2.1%-3.1%). Most were in functional class II/IV (64.3%) or I/IV (27.6%) of the New York Heart Association, and only 1.4% were in grade IV/IV. A consideration of confirmed angina could be made in 117 participants (19 after complete evaluation by a cardiologist and the rest due to definite angina and confirmed history of unstable angina, myocardial infarction, or coronary revascularization). The adjusted prevalence of confirmed angina was 1.4% (95%CI, 1.1%-1.8%) (Table 2 and Figure 2). Prevalence increased with age, with very low prevalence of definite angina (Rose) in participants between the ages of 40 and 50 years (< 1%) but progressively increasing to reach 7.1% in those between 70 and 80 years. The prevalences of definite (Rose) and confirmed angina by age and sex groups are presented in Table 2 and Figure 2. According to the Rose questionnaire, 125 (1.5%) and 779 (9.3%) participants met the criteria for possible and atypical angina, respectively.

Prevalence of Stable Angina (Definite Angina According to Rose Questionnaire and Confirmed Angina) by Sex and Age Groups

| Men | Women | Total | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | 95%CI | No. | % | 95%CI | No. | % | 95%CI | |

| Definite angina (Rose) | |||||||||

| 40-49 y | 939 | 0.5 | 0.0-1.0 | 1192 | 0.9 | 0.3-1.5 | 2131 | 0.7 | 0.3-1.1 |

| 50-59 y | 912 | 2.2 | 1.2-3.2 | 1090 | 1.2 | 0.5-2.0 | 2002 | 1.7 | 1.1-2.4 |

| 60-69 y | 909 | 1.5 | 0.5-2.5 | 885 | 2.0 | 1.0-3.0 | 1794 | 1.8 | 1.1-2.5 |

| 70-79 y | 706 | 5.2 | 2.3-8.1 | 879 | 8.6 | 4.9-12.3 | 1585 | 7.1 | 4.9-9.3 |

| ≥ 80 y | 373 | 6.1 | 2.1-10.2 | 493 | 5.3 | 2.9-7.7 | 866 | 5.6 | 3.5-7.7 |

| Total | 3839 | 2.2 | 1.6-2.9 | 4539 | 2.9 | 2.2-3.7 | 8378 | 2.6 | 2.1-3.1 |

| Confirmed angina | |||||||||

| 40-49 y | 939 | 0.3 | 0.0-0.8 | 1192 | 0.2 | 0.0-0.5 | 2131 | 0.3 | 0.0-0.6 |

| 50-59 y | 912 | 1.5 | 0.7-2.3 | 1090 | 0.6 | 0.1-1.0 | 2002 | 1.0 | 0.6-1.5 |

| 60-69 y | 909 | 0.8 | 0.1-1.6 | 885 | 0.7 | 0.2-1.2 | 1794 | 0.8 | 0.3-1.2 |

| 70-79 y | 706 | 4.5 | 1.6-7.3 | 879 | 4.2 | 1.9-6.5 | 1585 | 4.3 | 2.6-6.1 |

| ≥ 80 y | 373 | 2.9 | 0.3-5.6 | 493 | 2.1 | 0.5-3.8 | 866 | 2.4 | 1.0-3.8 |

| Total | 3839 | 1.5 | 1.0-2.1 | 4539 | 1.3 | 0.8-1.7 | 8378 | 1.4 | 1.0-1.8 |

95%CI, 95% confidence interval.

With the exception of active smoking, there was a higher frequency of coronary risk factors such as obesity, diabetes mellitus, hypercholesterolemia, and hypertension in patients with angina than in those without angina; patients with angina also showed more comorbidity related to arteriosclerosis (stroke, peripheral artery disease) or possibly caused by it (heart failure) (Tables 3 and 4; Tables 1 and 2 of the supplementary material). The prevalence of definite angina (Rose) tended to be higher in women, but the prevalence of confirmed angina was similar between the sexes (Table 1). In the multivariate analysis (Table 3), definite angina (Rose) was independently associated with age (OR=1.03), female sex (OR=1.84), obesity (OR=1.50), dyslipidemia (OR=2.52), and history of myocardial infarction (OR=2.06), unstable angina (OR=8.71), surgical revascularization (OR=3.23), or a diagnosis of heart failure (OR=2.50). The predictors of confirmed angina were age (OR=1.02), central obesity (OR=1.69), hypercholesterolemia (OR=5.36), hypertension (OR=2.26), peripheral artery disease (OR=2.12), and history of heart failure (OR=4.25), but not sex (Table 4).

Age- and Sex-adjusted Odds Ratios of Having Definite Angina (Rose Questionnaire) for Each Cardiovascular Risk Factor and Antecedent and the Final Multivariate Model

| OR (95%CI) | P | |

|---|---|---|

| CVRF | ||

| Obesity | 1.75 (1.24-2.47) | .001 |

| Overweight | 0.74 (0.52-1.06) | .1 |

| Central obesity | 1.82 (1.22-2.72) | .004 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 4.05 (2.85-5.75) | <.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 2.21 (1.39-3.50) | .001 |

| Current smoker | 0.58 (0.33-1.00) | .05 |

| Hypertension | 1.77 (1.06-2.94) | .028 |

| History | ||

| Stroke | 1.60 (0.90-2.86) | .108 |

| Peripheral artery disease | 2.85 (1.53-5.32) | .001 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 1.87 (1.10-3.16) | .02 |

| Thyroid disease | 1.39 (0.75-2.58) | .292 |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 8.18 (5.09-13.15) | <.001 |

| Unstable angina | 22.40 (13.53-37.07) | <.001 |

| Surgical revascularization | 19.06 (9.37-38.78) | <.001 |

| Percutaneous revascularization | 10.33 (5.46-19.53) | <.001 |

| Pacemaker implantation | 2.26 (0.92-5.58) | .076 |

| ICD implantation | 2.26 (0.92-5.58) | .076 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 19.36 (12.66-29.60) | <.001 |

| Previous diagnosis of HF | 5.26 (3.09-8.96) | <.001 |

| Multivariate model | ||

| Age | 1.03 (1.01-1.04) | <.001 |

| Sex | 1.84 (1.17-2.87) | .008 |

| Obesity | 1.50 (1.05-2.15) | .027 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 2.52 (1.66-3.83) | <.001 |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 2.06 (1.04-4.07) | .039 |

| Unstable angina | 8.71 (4.75-15.96) | <.001 |

| Surgical revascularization | 3.23 (1.20-8.69) | .021 |

| Previous diagnosis of HF | 2.50 (1.27-4.92) | .008 |

95%CI, 95% confidence interval; CVRF, cardiovascular risk factor; HF, heart failure; ICD, implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; OR, odds ratio.

Age- and Sex-adjusted Odds Ratios of Having Confirmed Angina for Each Cardiovascular Risk Factor and Antecedent and the Final Multivariate Model

| OR (95%CI) | P | |

|---|---|---|

| CVRF | ||

| Obesity | 1.59 (0.92-2.76) | .097 |

| Overweight | 0.76 (0.44-1.33) | .337 |

| Central obesity | 2.31 (1.40-3.80) | .001 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 6.90 (4.05-11.78) | <.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 2.00 (1.12-3.57) | .019 |

| Current smoker | 0.75 (0.38-1.46) | .398 |

| Hypertension | 3.81 (2.14-6.81) | <.001 |

| Antecedent | ||

| Stroke | 2.43 (1.21-4.88) | .012 |

| Peripheral artery disease | 3.13 (1.44-6.84) | .004 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 1.98 (1.03-3.82) | .041 |

| Thyroid disease | 1.41 (0.57-3.48) | .456 |

| Pacemaker implantation | 2.56 (0.86-7.64) | .091 |

| ICD implantation | 2.56 (0.86-7.64) | .091 |

| Previous diagnosis of HF | 5.60 (2.71-11.59) | <.001 |

| Multivariate model | ||

| Age | 1.02 (1.00-1.04) | .036 |

| Sex | 0.77 (0.44-1.36) | .369 |

| Central obesity | 1.69 (1.03-2.76) | .037 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 5.36 (3.08-9.34) | <.001 |

| Hypertension | 2.26 (1.22-4.17) | .009 |

| Peripheral artery disease | 2.12 (1.00-4.48) | .049 |

| Previous diagnosis of HF | 4.25 (2.09-8.66) | <.001 |

95%CI, 95% confidence interval; CVRF, cardiovascular risk factor; HF, heart failure; ICD, implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; OR, odds ratio.

Of the total population, 4.9% (413 of the 8378 study participants) had a history of ischemic heart disease (documented ACS or revascularization) (Table 1). Application of these data and the specific prevalences of angina by age and sex groups seen in the OFRECE study to the Spanish population (2011 census: 46 815 916 in-habitants, with 51.1% older than 40 years [23 922 933 inhabitants]), taking into account the study design, yields 1 151 350 (95%CI, 995 962-1 306 737) patients with this history of ischemic heart disease in Spain; only 274 480 (95%CI, 197 783-359 177) of these would show symptoms of angina (23.7%; 95%CI, 19.5%-28.0%).

DISCUSSIONThe prevalence of stable angina is difficult to establish because its diagnosis is eminently clinical4 and complex, expensive population studies are required for a reliable estimation. Most studies have used the Rose questionnaire,11 which, despite its limitations, is recommended by the World Health Organization for epidemiological studies12 and has been validated for use in Spain.8 This questionnaire is useful because it shows a good correlation with cardiovascular morbidity and mortality11,12 and has been validated and used in many countries, allowing comparisons with other historical Spanish series and data from other countries.16,17 As in most studies, angina was only considered diagnosed when patients met the definite angina criteria of the Rose questionnaire. The OFRECE study also used a second, more rigorous, definition of angina (confirmed angina), requiring diagnostic confirmation by a cardiologist or documented history of an ACS or coronary revascularization intervention. Few studies have used such stringent criteria, and those studies have also been quite variable, hindering comparisons.

Until the OFRECE study, no population-based re-evaluation of the prevalence of stable angina in Spain had been undertaken since the publication of the PANES study8 in 1999. The OFRECE study showed a low prevalence of stable angina in Spain in those aged 40 years or older under either of the definitions used (definite angina, Rose questionnaire: 2.6%; confirmed angina: 1.4%); however, the prevalence increased with age and, as would be expected, the frequency of CVRFs or diseases related to arteriosclerosis was significantly higher in patients with angina. Regardless of the definition used, the prevalence of angina seen in the OFRECE study was much lower than that detected in the other large study of the prevalence of angina carried out more than 15 years ago in Spain (the PANES study). Use of the definite angina (Rose) definition, applied in both studies, reduces the prevalence from 7.6% to 2.6%. This striking decrease probably has a multifactorial explanation that combines methodological and epidemiological aspects. On one hand, the design of the PANES study could allow biases that overestimate prevalence. On the other hand, therapeutic advances and more aggressive management strategies of ACS and stable angina mean that fewer and fewer patients end up with residual angina.6,7,17 Undoubtedly, the primary and secondary prevention efforts made by society and health care systems against cardiovascular diseases have also helped to reduce the prevalence of angina. Together, both aspects have probably reduced age-adjusted cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in developed countries.17–21 In the present study, only 24% of revascularized patients or those who have had an ACS event were symptomatic. This decreased prevalence in Spain is also seen when we compare our prevalence results with those of the REGICOR study,9 published in 1998 (2.6% vs 3.5%). The decreased prevalence of stable angina is in accordance with the trends seen in the epidemiology of coronary disease in Spain22,23 and in the rest of the developed world.17–21

This study permitted an estimate of the clinical situation facing patients with chronic coronary disease. For the first time in Spain, the workload can also be estimated: it is clearly high, with more than 1 150 000 patients with history of ischemic heart disease; about 24% of these would have asymptomatic angina. The remainder, more than 850 000, would require health care assistance focused on secondary prevention, which is also a burden for the health care system. Other recent studies24,25 show similar data. In the Spanish cohort of the CLARIFY (ProspeCtive observational LongitudinAl RegIstry oF patients with stable coronary arterY disease) studies,24 comprising 2257 patients with chronic ischemic heart disease, 21.8% had angina. As in the present study, most of these patients were in functional class of the New York Heart Association I/IV or II/IV (33% and 58% of patients, respectively). In the general CLARIFY study,25 22% of the 33 280 patients with ischemic heart disease had some degree of residual angina.

While we are mindful of the limitations inherent to comparisons between studies conducted using different methodologies and at different times, the prevalence of stable angina in Spain obtained in the OFRECE study seems lower, with either of the 2 definitions used, than that typically described in studies from Europe and the United States. The prevalence of definite angina (Rose) of 2.6% in participants older than 39 years is lower than that estimated for Europe4 (2%-4% of the population of all ages) and United States (5%).5 This lower prevalence is in line with the characteristically lower rates of coronary disease morbidity and mortality in Mediterranean countries such as Spain.20,21

The characteristics of the patients with stable angina in the OFRECE study are also generally associated with arteriosclerosis (Tables 1, 3 and 4; Tables 1 and 2 of the Supplementary Material): older age and higher rates of CVRFs and of history of cerebrovascular disease, peripheral artery disease, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The profile of patients with angina in this study is similar to that described in other Spanish and international studies.4,24–26 One controversial aspect is the prevalence according to sex. Classically, angina has been described as being more frequent in women, whereas the general prevalence of ischemic heart disease and ACS is higher in men. In this study, if the Rose questionnaire definition of angina is used, the prevalence is higher in women (OR=1.03; 95%CI, 1.01-1.04; P < .001) (Tables 1 and 3), whereas no clear differences are seen when a more stringent definition (confirmed angina) is used (OR=0.77; 95%CI, 0.44-1.36; P=.369). The 2 large studies16,27 that have analyzed the epidemiological differences in angina between the sexes show similar results to the OFRECE study. Prevalence increased with age, but it was lower in the oldest patients (> 80 years) than in those aged between 70 and 80 years (decreasing from 7.1% to 5.6%) (Table 2 and Figure 2). This drop is probably explained at least in part by the lower survival of patients with ischemic heart disease and the greater limitation of activity due to age-related comorbidity (musculoskeletal system and neurological problems) that avoids reaching the angina threshold.25 The other notable aspect is the negative association between active smoking and angina (definite angina: OR=0.58; 95%CI, 0.33-1.00) (Table 3). This association is distinct from “smoker's paradox”, a phenomenon seen in studies from the 1980s and 1990s of a better prognosis for smokers after an ACS and which remains to be reproduced.28 In the present study, the negative association disappears in the multivariate analysis. Thus, smoking does not appear to be an independent factor and was probably associated with angina because most patients with “definite angina” have received guidance on secondary prevention measures.

LimitationsThe definitions and criteria of angina used in this study have already been described, as well as their limitations. As in many epidemiological studies, the main study limitations are related to sample selection. In this case, the choice of the health care areas analyzed in each province was not random. We believe that this would have a minimal effect, if any, because the prevalence of angina would be unlikely to vary markedly in adjacent areas. More important is the random selection of physicians and, particularly, of participants linked with each physician, a characteristic of the study design that strengthens the results. The high number of sampling points improved the representativeness of the sample, which can be difficult to evaluate. A limitation inherent to this type of general population study is that the participants can differ from those unable to participate. Although it is impossible to completely discard a potential selection bias, the size of the bias would probably be small because the participation was excellent for this type of study (76% of those whom we tried to contact); only one third of the losses during recruitment were individuals who declined participation.

CONCLUSIONSThe prevalence of stable angina in the Spanish population aged 40 years or older was 2.6% using the Rose questionnaire definition of definite angina and 1.4% when history of ACS or revascularization was also required. The data indicate that the prevalence of stable angina in Spain has decreased in the last decade and is lower than the overall rate observed in Europe and the United States. The prevalence increased with age and an association was seen between angina and the main CVRFs and history of arteriosclerotic disease.

FUNDINGThe OFRECE study was supported by the Research Agency of the Spanish Society of Cardiology (Agencia de Investigación de la Sociedad Española de Cardiología). This study has been financed by a grant from the Observatorio de la Mujer of the Agencia de Calidad del Ministerio de Sanidad and by an unconditional grant from SANOFI (which was not involved in the study design, data analysis, or preparation of the final manuscript).

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTSNone declared.

A list of the contributors to the OFRECE (Observación de Fibrilación y Enfermedad Coronaria en España [Observation of Fibrillation and Coronary Disease in Spain]) study is included in Appendix 1 of the supplementary material.