Malignant pericardial effusion has a high recurrence rate after pericardiocentesis. We sought to confirm the efficacy of percutaneous balloon pericardiotomy as the initial treatment of choice for these effusions.

MethodsRetrospective analysis of the clinical, echocardiographic, and follow-up characteristics of a consecutive series of percutaneous balloon pericardiotomies carried out in a single center in patients with advanced cancer.

ResultsSeventeen percutaneous balloon pericardiotomies were performed in 16 patients with a mean age of 66.2 (15.2) years. Fourteen patients had pathologically confirmed metastatic neoplastic disease, 3 had previously required pericardiocentesis, and in the remaining patients percutaneous balloon pericardiotomy was the first treatment for the effusion. All patients had a severe circumferential effusion, and most presented evidence of hemodynamic compromise on echocardiography. In all cases, the procedure was successful, there were no acute complications, and it was well tolerated at the first attempt. There were no infectious complications during follow-up (median, 44 [interquartile range, 36-225] days). One patient developed a large pleural effusion that did not require treatment. Three patients needed a new pericardial procedure: 2 had elective pericardial window surgeries and 1 had a second percutaneous balloon pericardiotomy.

ConclusionsPercutaneous balloon pericardiotomy is a simple, safe technique that can be effective in the prevention of recurrence in many patients with severe malignant pericardial effusion. The characteristics of this procedure make it particularly useful in this group of patients to avoid more aggressive, poorly tolerated approaches.

Keywords

.

INTRODUCTIONThe development of malignant pericardial effusion (MPE) over the course of an oncologic disease is a complication that significantly worsens the prognosis1,2 and can be ultimately fatal. In general, the mean survival time of these patients does not exceed 5 months;1–4 hence, in most cases it seems reasonable to focus management of the effusion on the relief of symptoms and prevention of recurrence.

For decades, pericardiocentesis has been the standard treatment for MPE5 and currently, 25% to 44% of in-hospital pericardiocentesis procedures are performed in patients with this type of effusion.1,2 Nonetheless, it is known that a neoplastic cause is an independent risk factor for recurrent effusion following pericardiocentesis,2,6 with reported recurrence rates reaching 36% to 62% in this population.7,8 This implies that patients with MPE have a 5-fold greater probability of requiring a new pericardiocentesis than patients with effusions having a non-neoplastic cause.1

In 1991, Palacios et al.9 described a new percutaneous technique to avoid recurrent effusion, consisting in creation of a pericardial window by balloon inflation. Over the years this technique has proven to be safe and effective,10–19 and recently it has been suggested that percutaneous balloon pericardiotomy (PBP) could be the initial treatment of choice in patients with symptomatic MPE.19

METHODSA retrospective review was performed of the medical histories and echocardiographic and fluoroscopic images of patients with suspected or previously confirmed MPE undergoing PBP in our center. Clinical cardiologic and oncologic variables were recorded, as well as the short- and medium-term outcome of the procedure, the acute complications, the rate of recurrent effusions, and the need for a new procedure.

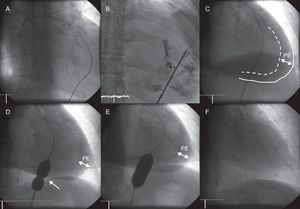

ProcedureThe procedure is done under conscious sedation and analgesia (midazolam 1-2 mg iv and morphine 2.5 mg i.v., repeating the dose of both agents before balloon inflation if required), antibiotic prophylaxis (cefazolin 1 g/8 h i.v., starting before the procedure, with a total of 3 doses), and fluoroscopic guidance. The pericardial effusion is reached through a percutaneous subxiphoid approach, in accordance with the conventional technique for pericardiocentesis. Initially, after extracting a small amount of effusion, a few milliliters of iodated contrast material is injected through the drainage catheter to better delineate the pericardial space. Subsequently, with the help of a 0.035-inch exchange guidewire and a 10 F to 12 F introducer, a dilatation balloon is placed through the parietal pericardium and various manual inflations are carried out until the indentation in the balloon created by the pericardium completely disappears. The procedure is completed by manual aspiration of the pericardial fluid, achieved by withdrawing the dilatation balloon over the exchange guidewire and reintroducing the drainage catheter, using fluoroscopy to guide the catheter to the remaining areas of effusion. Before the patient leaves the catheterization laboratory, transthoracic echocardiography is performed to confirm the absence of complications and disappearance of the pericardial effusion (Fig. 1). In most cases, the drainage catheter is removed at this time. Radiologic follow-up is recommended at 24 to 48 h, and echocardiographic follow-up at 48 to 72 h to rule out the development of significant pleural effusion and recurrent pericardial effusion.

Percutaneous balloon pericardiotomy. A: Subxiphoid percutaneous access to the pericardial space. B: Injection of 10-15 mL iodated contrast material. C: Visualization of pericardial effusion, cardiac silhouette (discontinuous line), and parietal pericardium (continuous line). D and E: Repeated balloon inflations to achieve gradual reduction of the indentation in the balloon created by the pericardium (arrow), until total disappearance. F: Final result after balloon pericardiotomy and complete pericardial fluid drainage. PE, pericardial effusion.

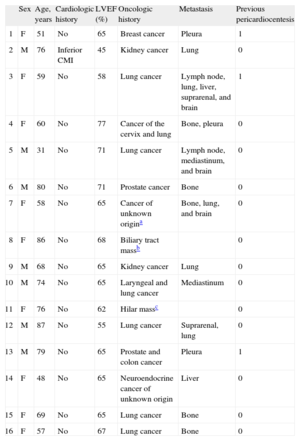

Since April 2008, 17 PBPs have been performed in 16 patients with suspected or previously confirmed MPE. The demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 1. The mean age of the series was 66.2 (15.2) [31-87] years, and there were 9 women. Only 1 patient had a known cardiologic history, 13 patients had previous pathologic confirmation of oncologic disease, in another patient the study of pericardial fluid obtained during PBP was confirmatory, and additional studies were not performed in 2 others because of the presence of biliary and hilar masses of unknown origin, which radiologic study indicated were neoplastic disease. The 14 patients with a diagnosis of pathology had advanced cancer, with metastasis in various organs in addition to the pericardium. Three patients had previously required pericardiocentesis to treat cardiac tamponade, and in these cases PBP was carried out in a second procedure because of recurrent effusion, whereas in the remaining 13 patients PBP was the first procedure used to treat their pericardial effusion.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of the Patients

| Sex | Age, years | Cardiologic history | LVEF (%) | Oncologic history | Metastasis | Previous pericardiocentesis | |

| 1 | F | 51 | No | 65 | Breast cancer | Pleura | 1 |

| 2 | M | 76 | Inferior CMI | 45 | Kidney cancer | Lung | 0 |

| 3 | F | 59 | No | 58 | Lung cancer | Lymph node, lung, liver, suprarenal, and brain | 1 |

| 4 | F | 60 | No | 77 | Cancer of the cervix and lung | Bone, pleura | 0 |

| 5 | M | 31 | No | 71 | Lung cancer | Lymph node, mediastinum, and brain | 0 |

| 6 | M | 80 | No | 71 | Prostate cancer | Bone | 0 |

| 7 | F | 58 | No | 65 | Cancer of unknown origina | Bone, lung, and brain | 0 |

| 8 | F | 86 | No | 68 | Biliary tract massb | 0 | |

| 9 | M | 68 | No | 65 | Kidney cancer | Lung | 0 |

| 10 | M | 74 | No | 65 | Laryngeal and lung cancer | Mediastinum | 0 |

| 11 | F | 76 | No | 62 | Hilar massc | 0 | |

| 12 | M | 87 | No | 55 | Lung cancer | Suprarenal, lung | 0 |

| 13 | M | 79 | No | 65 | Prostate and colon cancer | Pleura | 1 |

| 14 | F | 48 | No | 65 | Neuroendocrine cancer of unknown origin | Liver | 0 |

| 15 | F | 69 | No | 65 | Lung cancer | Bone | 0 |

| 16 | F | 57 | No | 67 | Lung cancer | Bone | 0 |

CMI, chronic myocardial infarction; F, female; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; M, male.

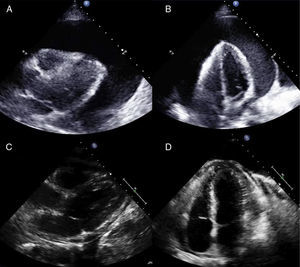

The indication for PBP in all cases was a severe (≥20 mm) circumferential pericardial effusion (Fig. 2). Most patients additionally showed various echocardiographic signs of hemodynamic compromise. Five of the available follow-up echocardiograms performed in the first 72 h showed moderate or severe recurrence of pericardial effusion, although signs of hemodynamic compromise were only observed in 2 cases. In 2 of these 5 patients the recurrent effusion was localized and not circumferential (Table 2).

Example of a severe circumferential malignant pericardial effusion treated by percutaneous balloon pericardiotomy (patient 5) and follow-up at 8 months with no new procedures. A and B: Parasternal and apical views showing the severe malignant effusion (40 mm) before treatment with percutaneous balloon pericardiotomy. C and D: Parasternal and apical views at 8 months, in which only a very small pericardial effusion is seen.

Echocardiographic Characteristics of Malignant Effusions Treated With Percutaneous Balloon Pericardiotomy

| pre-PBP effusion, mm | Echocardiographic evidence of hemodynamic compromise | Echocardiogram<72 h post-PBP | |

| 1 | 30 | RA and RV collapse | Moderate posterolateral effusion, no hemodynamic compromise |

| 2 | 35 | Respiratory-induced changes in transmitral flow | No effusion |

| 3 | 35 | RA and RV collapse, respiratory changes in transmitral flow | Very small effusion |

| 4 | 25 | RA, RV, and LA collapse | Very small effusion |

| 5 | 40 | RA and RV collapse, respiratory changes in transmitral and transtricuspid flow | Not availablea |

| 6 | 34 | RA and RV collapse, respiratory changes in transmitral and transaortic flow | No effusion |

| 7 | 25 | RA, RV, and LA collapse | Small circumferential effusion |

| 8 | 30 | Not present | Severe circumferential effusion, no hemodynamic compromise |

| 9 | 35 | RA collapse respiratory changes in transmitral flow | Severe anterolateral organized effusion, with RA collapse and less marked respiratory changes in transmitral flow |

| 10 | 27 | Respiratory changes in transmitral and transtricuspid flow | Small circumferential effusion |

| 11 | 24 | RA and RV collapse, respiratory changes in transmitral and transaortic flow | Not available |

| 12 | 25 | RA and RV collapse | Very small effusion |

| 13 | 39 | RA and RV collapse | Not available |

| 14 | 50 | RA, RV, and LA collapse | Severe circumferential effusion (30 mm), no hemodynamic compromise |

| 15 | 22 | RA and RV collapse | Small circumferential effusion |

| 16 | 20 | RA and RV collapse | Moderate circumferential effusion (17 mm) with partial collapse of right chambersb |

LA, left atrium; PBP, percutaneous balloon pericardiocentesis; RA, right atrium; RV, right ventricle.

In all cases, PBP was carried out as an elective procedure. Procedure success, defined as total disappearance of the indentation on balloon inflation and an absence of significant pericardial effusion at completion of the intervention, was achieved at the first attempt in all patients. The type, amount, and pathology findings of the drained pericardial effusion, and the size of the dilatation balloon used in each case are shown in Table 3. No acute PBP-related complications occurred in the catheterization laboratory, and the procedure was well tolerated in all patients with the sedation and analgesia administered.

Characteristics of Pericardial Fluid and the Dilatation Balloons Used

| Amount of pericardial fluid extracted, mL | Type of pericardial fluid extracted | Pathologic study of extracted pericardial fluid | Dilatation balloon, width×length | |

| 1 | 750 | Sanguineous | Breast tumor cells | 18 mm×3 cma |

| 2 | 1400 | Serosanguineous | Kidney tumor cells | 16 mm×3 cma |

| 3 | 1000 | Serosanguineous | Lung tumor cells | 18 mm×4 cmb |

| 4 | 550 | Sanguineous | Lung tumor cells | 20 mm×4 cmb |

| 5 | 1500 | Sanguineous | Lung tumor cells | 22 mm×4 cmb |

| 6 | 950 | Sanguineous | No tumor cells | 20 mm×4 cmb |

| 7 | 220 | Serosanguineous | Lung tumor cells | 18 mm×4 cmb |

| 8 | 850 | Sanguineous | Sample not available | 16 mm×4 cmb |

| 9 | 650 | Sanguineous | Sample not availablec | 18 mm×3 cmd |

| 10 | 550 | Sanguineous | Sample not available | 18 mm×4 cmb |

| 11 | 700 | Serosanguineous | Sample not available | 18 mm×4 cmd |

| 12 | 750 | Serosanguineous | Lung tumor cells | 18 mm×4 cmb |

| 13 | 1000 | Sanguineous | Colon tumor cells | 20 mm×4 cmb |

| 14 | 1000 | Serous | No tumor cells. Inflammatory smear | 16 mm×6 cmb |

| 15 | 700 | Sanguineous | Lung tumor cells | 20 mm×4 cmb |

| 16 | 700 | Sanguineous | Lung tumor cells | 20 mm×4 cmb |

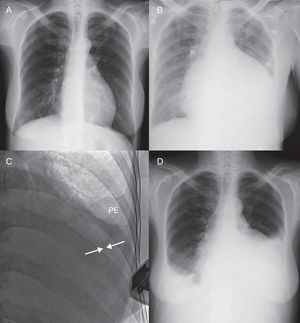

Patient follow-up until August 2012 or death lasted a median of 44 days [interquartile range, 36-225 days]. During hospitalization following PBP, there were no cases of fever and no other signs or symptoms of infection attributable to the procedure in any case. In a single case (patient 14), there was a marked worsening of left pleural effusion following PBP, but there were no symptoms; hence, drainage was not deemed necessary (Fig. 3). Although only 1 patient was in frank cardiac tamponade at the time of PBP, 12 patients reported an improvement in their overall status, mainly because of the reduction in dyspnea. Over the clinical course, a new pericardial procedure was required in 3 patients. Elective pericardial window surgery was performed in 2 patients due to severe localized recurrent pericardial effusion. In the first of these, the surgical window was created 79 days following PBP to treat a slowly progressive accumulation of effusion, whereas in the second, the window was required at 72 h following PBP because of fast fluid accumulation and echocardiographic evidence of hemodynamic compromise. In a third case (patient 16), despite the initial success of the procedure and clear improvement of the patient's symptoms in the hours following PBP, a new PBP was requested at 48 h (22mm×4 cm balloon; 350 mL of hematic fluid) because of recurrence of a moderate (17 mm) circumferential pericardial effusion and symptoms of dyspnea at rest. Of note, at 1 month following this second PBP there was no evidence of pericardial effusion on the control echocardiogram (Table 4).

Radiologic evolution following percutaneous balloon pericardiotomy (patient 14). A: Chest x-ray performed 2 months previously shows no significant pathology findings. B: 1 day before percutaneous balloon pericardiotomy, a considerable increase in the cardiothoracic index was observed. C: Following the procedure, fluoroscopy and echocardiography demonstrate persistence of a very small pericardial effusion (arrows), with a small amount of pleural effusion occupying the left costophrenic sinus. D: At 48 h, there is a marked increase in left and right pleural effusion and the cardiothoracic index remains increased; at this time there was a severe pericardial effusion, although smaller than before the procedure. PE, pleural effusion.

Evolution of Patients Treated by Percutaneous Balloon Pericardiotomy

| Status in August 2012 | Follow-up, days | Pericardial reoperation, time since PBP | Reason for new pericardial procedure following PBP | |

| 1 | Died | 150 | Yes, surgical window (79 days) | Recurrence of severe encapsulated effusion located on the anterolateral side and apex, with evidence of hemodynamic compromise |

| 2 | Died | 340 | No | — |

| 3 | Died | 28 | No | — |

| 4 | Died | 208 | No | — |

| 5 | Died | 286 | No | — |

| 6 | Alive | 485 | No | — |

| 7 | Died | 276 | No | — |

| 8 | Died | 19 | No | — |

| 9 | Died | 46 | Yes, surgical window (72 h) | Recurrence of severe encapsulated effusion located on the anterolateral side, with evidence of hemodynamic compromise |

| 10 | Died | 74 | No | — |

| 11 | Died | 5 | No | — |

| 12 | Died | 40 | No | — |

| 13 | Died | 39 | No | — |

| 14 | Alive | 42 | No | |

| 15 | Died | 9 | No | |

| 16 | Alive | 40 | Yes, new PBP (48 h) | Recurrence of moderate circumferential effusion with evidence of incipient hemodynamic compromise |

PBP, percutaneous balloon pericardiotomy.

The results of the present study show that PBP enables complete drainage of effusion in a single, fast, simple percutaneous procedure, and avoids new interventions in most cases. These findings and the favorable safety and tolerability profile lead us to consider that PBP can be the initial treatment of choice for severe pericardial effusion and clinical or hemodynamic deterioration in patients with advanced oncologic disease and a limited life expectancy.

The true prevalence of MPE is unknown and varies according to the type of cancer and diagnostic method used. Lung cancer remains the cause of most MPE cases,1,4,19 as occurred in 8 of our patients. Furthermore, it is likely that MPE detection will significantly increase over the coming years, given the increasing incidence of cancer and widespread use of cardiac imaging techniques. This trend is illustrated by the fact that neoplastic disease is now the main cause of pericardial effusion1 and cardiac tamponade3,6 in many hospitals.

A treatment plan for symptomatic MPE should be established in this patient population who (as our series confirms) have a limited life expectancy.1–4 To our mind, the ideal method should be simple and should alleviate the symptoms, produce little morbidity and mortality, require only a short hospitalization, lead to a small number of repeat pericardial procedures, and facilitate etiologic diagnosis of the effusion. Pericardiocentesis is the simplest standard procedure, but it has the drawback of a high recurrence rate and the need for repeat procedures.1,7,8 Although continuous pericardial drainage manages to reduce recurrences, it significantly lengthens hospitalization time and carries a high risk of infection.6,7 The use of sclerosing agents also requires maintenance of the drainage catheter and several days of hospitalization, and this treatment can cause intense pain,20 arrhythmia, and constrictive or effuso-constrictive pericarditis.21 Lastly, treatment with a surgical pericardial window is more complex, less well tolerated, and is associated with considerable morbidity related to the anesthesia, surgery, and postoperative period.4,7 Furthermore, this approach has not consistently shown greater precision for the etiologic diagnosis of pericardial effusion as compared to conventional pericardiocentesis.22 If one additionally takes into account that up to 10% of pericardial effusions treated by a surgical window require a new intervention because of recurrence within the first month,23 and that PBP is less costly than pericardiocentesis followed by pericardial window surgery,18 it is reasonable to think that this last technique is not the most suitable for the type of patient under study.

Percutaneous creation of pericardial window as an alternative to surgery was first described9 as a complementary technique to continuous pericardial drainage in patients who persistently drain >100 mL/24 h during 3 days. Nonetheless, already in the second published series,10 50% of patients had undergone PBP as the initial therapy for pericardial perfusion and (as also occurred in later series11,15) the results did not differ from those of patients initially treated by continuous drainage, followed by PBP. In both cases, PBP would avoid recurrence by facilitating pericardial drainage to the pleural (Fig. 3) or peritoneal cavity, where there is a greater capacity for resorption, and by promoting possible fusion of the pericardial layers.10

As we described, PBP using a small percutaneous approach is a simple and well-tolerated procedure that alleviates many of the patients’ symptoms without the need for lengthy aftercare, which unnecessarily prolongs hospitalization. Even though large, circumferential MPEs were treated in the series presented here (Table 2, Fig. 2), there were no complications during PBP, in keeping with previous reports,11–13,15,19 nor were there procedure-related infections using the proposed antibiotic prophylaxis.10 Furthermore, in contrast to some previous studies in which a considerable incidence of pleural effusion requiring drainage was reported following PBP,10,15,17 only 1 patient in our series presented a large pleural effusion–which did not require drainage, likely because of the complete manual aspiration of MPE performed before the procedure was considered finalized.

Lastly, with regard to the efficacy of PBP, the number of pericardial reinterventions performed in our patients might seem high, but in 2 of these 3 cases, the procedure was needed because of formation of an encapsulated effusion. This likely does not indicate failure of the technique, but rather a limitation of the technique and of surgical pericardial windows in themselves.

CONCLUSIONSIn light of the demonstrated ease, tolerability, and efficacy of the technique, and with the ultimate aim of palliating the symptoms and providing the maximum quality of life possible, we conclude that PBP can feasibly be the initial treatment of choice for severe, symptomatic MPE in patients with advanced oncologic disease.

FUNDINGDr. Juan Ruiz-García is grateful for the economic support received from the Spanish Society of Cardiology through the 2011 grant for Post-Residency Research Training from the Cardiac Catheterization and Interventional Cardiology Section.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTNone declared.