To the Editor:

One hundred years have passed since the achievement of Dr Carlos Chagas (April 14, 1909), who, under inhospitable conditions, had the intelligence and ability to humbly detect an unknown illness that we now know originates from pre-Columbian America1 (Figure 1A). We must attribute particular merit to the discovery of the parasite (Trypanosoma cruzi in honour of Oswaldo Cruz) and subsequently the illness (Figure 2).

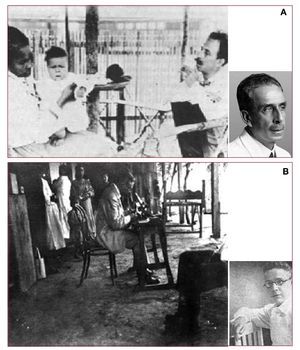

Figure 1. A: Dr Carlos Chagas in Lassance, Minas Gerais, Brazil with Berenice, the first person in which Trypanosoma cruzi was identified. B: Dr Salvador Mazza and his untiring research into the disease, using the microscope.

Figure 2. Trypanosoma cruzi (aetiological agent) and vinchuca (vector), taken from the figures published in the original article by Dr Carlos Chagas in 1909.

How important has this original discovery in medical science been in the academic and political fields over the last one hundred years? Without wanting to judge what has been done well and what has not, the history of this "forgotten" illness is briefly summarised below. The following timeline only serves as an outline and the dates are not necessarily exact, but conceptually it attempts to show the actions of our scientific communities over the past century.

1909-1919. Founding stage, which includes all Carlos Chagas publications and international recognition of his findings.2 The aetiological agent and the illness are acknowledged, but not the population who are sufferers.

1919-1929. Discredit, due at least in part, to the error of confusing the signs of the illness with endemic hypothyrodism. Publications on the subject disappear.

1929-1939. Re-dimensioning of the illness due to Dr Salvador Mazza, who opened the studies up to a large number of cases for the first time.3 (Figure 1B).

1940-1950. Acknowledgement of the acute stage and the infection mechanisms of American trypanosomiasis. Emphasis is put on the need to eliminate the insect vector.

1950-1960. Epidemiological assessment of the health problem, generated from epidemiological field studies and the use of ECG as a tool for distinguishing between health and illness. Concrete measures are taken to counteract it.

1960-1980. Foundation of specialised institutes, education and prevention campaigns and advances in pharmacological anti-parasitic treatment.

1980-1990. Discredit of treatment for the chronic phase and consolidation of the measures for eliminating the insect vector.

1990-2009. Noticeable reduction in the number of pharmacological and clinical studies, with an increase in basic research, molecular and genetic biology applied to Chagas disease. Reconsideration of the anti-parasitic treatment for the chronic phase,4 and at least transitory elimination of the insect vector in some countries.

An analysis of the publications from the last 10 years using the PubMed database and the key words Chagas and Trypanosoma cruzi has produced surprising results: more than 70% of the research work was basic/experimental (1401 of 1899 studies) and almost 80% was published in journals in countries where the endemic was not present (1488 of 1899 studies). This perhaps reflects the problems surrounding the research itself, and independently of research in general, in developing countries.

How is it then that, 100 years later, the illness continues to be rife and even shows a tendency towards globalisation? Perhaps we need to answer with the popular sentence "Chagas is a disease of poor people." We also need to ask ourselves: Who is this research for? Are the aims of anti-Chagas programmes being evaluated? What degree of importance do scientific societies place on Chagas

disease? From the point of view of a person suffering from Chagas, the research resources have to date not brought the desired benefits. It is difficult for anti-Chagas programmes to reach the sufferers and scientific societies have not given enough importance to them. A further question is: Are there insufficient research resources, or are the socioeconomic conditions of the sufferers simply insufficient? We believe that the second statement is more realistic and that the complexity of the illness is difficult to deal with using insecticides, drugs, electrocardiograms or genetic studies. Chagas sufferers have few measures available to them for generating or demanding solutions, and they don't speak up due to lack of education and "social importance."

One hundred years have passed and science, medicine, technology, and bioethics have advanced as never before over these recent decades. However, poverty, lack of education, stress and access to health services have not favourably accompanied this development. The actual prevention (elimination of the vector) and control of Chagas disease will continue to depend on the political and economic future of those countries suffering from the endemic. The disease will not be controlled only by health actions based on medical and technological advances alone. It will also depend on the socioeconomic development of the people involved.5 Sadly, Chagas disease continues to exist more than one hundred years after the first case diagnosis. As is the case with many problems, we must deal with the issue on an integral level so that our actions are all-encompassing and do not help only the lucky ones.