This article describes the contribution of the decrease in cardiovascular mortality to the increase in life expectancy at birth in Spain from 1980 to 2009. We explain the demographic factors underlying the decrease in mortality from cardiovascular diseases at older ages and the effect of this decrease on lifespan.

MethodsThe contribution of these decreases to Spanish life expectancy at birth was calculated using decomposition methods for life expectancy. We calculated standardized mortality rates by sex and 3 causes of death (cerebrovascular disease, ischemic heart disease, and other heart disease) for 3 age groups: 65 to 79 years, 80 to 89 years, and ≥90 years.

ResultsFrom 1980 to 2009, life expectancy at birth in Spain increased by more than 6 years for both sexes. The contribution of the decrease in cardiovascular mortality to the total increase in life expectancy at birth was 63% among women and 53% among men. Among the ≥65-year-old age group, this contribution was 93% among women and 87% among men.

ConclusionsThe decrease in cardiovascular mortality, mainly at older ages, has been the main contributor to increased Spanish life expectancy at birth during the last 3 decades.

Keywords

The belief that mortality at older ages is an intractable problem has been widely held by researchers in recent decades.1 Several studies have drawn attention to limits to the mean duration of human life, survival rates that can barely be improved on,2,3 and—surprisingly—difficulties in reducing endogenous mortality.3,4

However, empirical evidence shows an epidemiological transition characterized by a shift in less deadly and more chronic and degenerative diseases to older ages,5,6 in which there has been a decrease in mortality rates from endogenous causes of death. Three facts support this evidence. First, survival at older ages is susceptible to substantial improvement. Second, life expectancy (LE) has steadily increased in demographically developed countries over the past 2 centuries.7 Third, research based on biodemographic models8,9 and heterogeneous and fragile populations10 has shown that mortality in general, and endogenous mortality in particular, are modifiable, a fact that is more evident at older ages.11,12 All this indicates a decrease in mortality, due to increased survival, which has shifted to increasingly older ages. In other words, aging has slowed down while survival and life span have increased.

In this context, LE at birth in Spain grew by 6.03 years among women (up to 84.5 years old) and by 6.17 years among men (up to 78.5 years old) from 1980 to 2009. Given this situation, the aim of this study was to explain the contribution of the decrease in cardiovascular mortality (especially among the elderly) to the increase in LE in the Spanish population during this period.

METHODSDataData on death by age, sex, and cause of death in Spain were obtained from the Vital Statistics for 1980-2009 published by the National Institute of Statistics. During this period, data on deaths were recorded in 2 revisions of the International Classification of Diseases: the ninth revision, which covered the period 1980-1998, and the tenth revision, which covered the period 1999-2009. On the basis of these sources, a homogenization and regrouping process was performed13 addressing, on the one hand, cardiovascular diseases, and on the other, cerebrovascular diseases, ischemic heart disease (IHD), and other heart diseases. Finally, the Spanish mortality tables for this period were obtained from the online Human Mortality Database.14

Statistical AnalysisThe decomposition method for LE was used to calculate the weight of the factors that have influenced the change in LE in the Spanish population (sex, age, period, and cause of death).15–17 This method consists of decomposing the difference between 2 specific LEs (for 2 periods, 2 populations or by sex) in relation to the contribution of age, cause of death, or both. We calculated the increase or decrease in LE attributed to the change in mortality from the diseases studied by period, population, and sex.

The contribution of different cardiovascular diseases to mortality was calculated for 5-year age intervals and by sex for 3 older age groups (65-79 years, 80-89 years, and ≥90 years).

The results obtained by calculating the contributions to LE were complemented by analyzing mortality by cause. Changing patterns in LE between 1980 and 2009 were calculated by using the logarithm of the standardized mortality rates by age, sex, and cause, thus avoiding the effect of age on mortality due to the aging process. This approach also allows comparison of trends over the entire period.18 The standard population used was the total Spanish population at risk of dying in 1991; these data were obtained from the Human Mortality Database. Although another year could have been chosen, 1991 was selected because it was a census year.

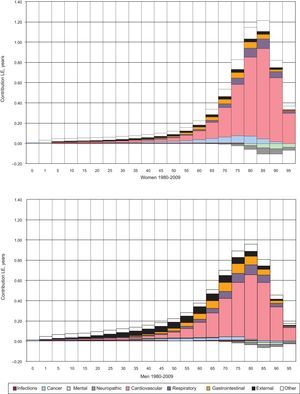

RESULTSFor causes of death, in the period 1980-2009 the greatest contribution to increased LE at birth was attributable to the decrease in cardiovascular mortality. Figure 1 shows in detail its contribution to the change in LE and those of the other major causes of death over the entire life span. The increase in LE due to the decrease in mortality from cardiovascular disease was 3.8 years (63% of the total increase) for women and 3.3 years (53% of the total increase) for men. These increases mainly occurred in the ≥65-year-old group; in this group, the contribution of the decrease in mortality from cardiovascular disease to the total increase in LE was 93% among women (25% in individuals aged 65-79 years, 44% in those aged 80-89 years, and 24% in those aged ≥90 years) and 87% in men (36%, 37%, and 14%, respectively).

Contributions of the change in cardiovascular disease mortality (and 8 other causes of death) to the variation in life expectancy at birth by sex (Spain, 1980-2009). LE, life expectancy. Source: own work based on data from the National Institute of Statistics and the Human Mortality Database.

The contribution of the decrease in mortality from other diseases to increased LE was much smaller: respiratory diseases, 7.7% in women and 9.0% men; cancer, 7.0% in women and 3.2% men; gastrointestinal diseases, 5.6% in women and 9.6% men; and external causes, 5.1% in women and 12.8% men. In contrast, mortality from nervous system diseases and mental and behavioral disorders had a negative contribution, which was higher in women (3% per group) than in men (1%).

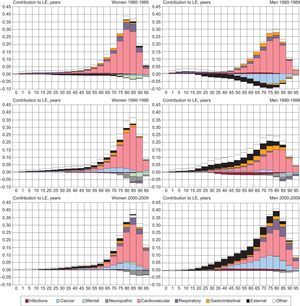

The data show that the increase in LE in the period 1980-2009 was predominantly attributable to the decrease in mortality from cardiovascular disease and the decrease in mortality among older people. There has been an obvious chronological shift of the effect of these contributions to increasingly older ages (Fig. 2). In women aged between 65 and 79 years there was a decrease from 33% in the period 1980-1989 to 20% in the period 2000-2009; in individuals aged between 80 and 89 years, the figure remained stable at around 44%, and among those aged ≥90 years, there was an increase from 14% to 33%. In addition, the contribution of cardiovascular disease to the total increase in LE was relatively low: among women, this was 69% in the period 1980-1989; 65% in 1990-1999; and 55% in 2000-2009. The figures for men were 110%, 45% and 33%, respectively. As summary data, the contribution per decade of all 3 age groups remained close to 90%.

Contributions of the change in cardiovascular disease mortality (and 8 other causes of death) to the variation in life expectancy at birth by sex (Spain, 1980-1989, 1990-1999, and 2000-2009). LE, life expectancy. Source: own work based on data from the National Institute of Statistics and the Human Mortality Database.

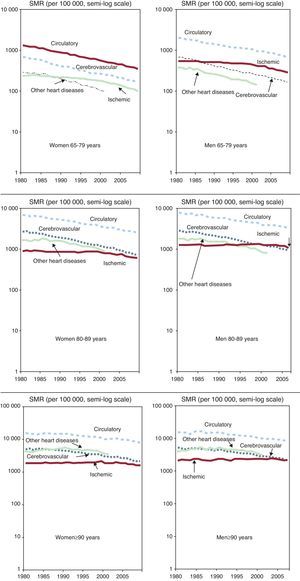

As already confirmed in other studies,19–22 mortality from cardiovascular disease decreased in the 3 age groups analyzed. The relevance of this change in later life and its fundamental impact on the increase in LE indicates the need to disaggregate mortality into 3 causes of death: cerebrovascular disease, IHD, and other heart diseases (Fig. 3).

Standardized mortality rates by sex and by age group (65-79 years, 80-89 years, and ≥90 years) for cardiovascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, ischemic heart disease, and other heart diseases (Spain, 1980-2009). SMR, standardized mortality rate. Source: own work based on data from the National Institute of Statistics and the Human Mortality Database.

Mortality from cerebrovascular disease has been the only cause that has consistently decreased in both sexes, in the 3 age groups considered, and throughout the period 1980-2009. There were 2 particular features related to mortality from IHD (myocardial infarction and angina pectoris being the main components): increased mortality among men at all ages and relative stability throughout the entire period for both sexes. Figure 3 shows some slight decreases at the end of the period, particularly among the 65- to 79-year-old group; these decreases were somewhat lower among the other 2 groups. Finally, mortality from other heart diseases has also generally decreased, except in the ≥90-year-old group.

DISCUSSIONThe marked decrease in cardiovascular mortality at older ages in Spain during the period 1980-2009 has made an enormous contribution to the increase in LE at birth.

Cardiovascular mortality rates are lower than those in most European countries. Western European countries have followed a pattern of decreased cardiovascular mortality similar to that observed in Spain, with a decrease of about 60% in women and of 50% in men. However, this decrease did not occur in Eastern European countries until the 1990s.23 Cardiovascular mortality is comparatively lower in Spain than in most European countries, particularly IHD mortality throughout Spain and mortality from cerebrovascular diseases in northern Spain.24 A paradox occurs in southern Europe, as countries in this region have lower IHD mortality than in northern Europe, despite increased saturated fat intake. This paradox is generally thought to be related to the Mediterranean diet, but recent studies have postulated that it could be related to the increased prevalence of stable atherosclerotic plaque.25

From the demographic point of view, there may be a cohort effect in Spain. The generations now reaching older ages experienced their childhoods under difficult social conditions (influenza, wars, poor sanitary conditions, and a diet typical of the early 20th century). Theories of natural selection in survival,26 food shortages,27 low weight at birth and during childhood,28 and fetal growth29,30 could provide plausible explanations for the decrease in cardiovascular diseases in the Spanish population.

Decreased cardiovascular mortality can probably be attributed to the successful combination of public health policies, the improved management of risk factors in clinical practice, and behavioral changes.31 These factors should be investigated in future studies.

Finally, it should be stressed that the use of standardized total mortality rates tends to place greater weight on the most frequent causes of death at older ages, when the bulk of deaths occur. Deaths among young people or adults are usually due to causes that could be avoided by the implementation of social or health measures and therefore their impact is far greater than that of death due to causes that are more closely associated with biological or life cycles and that reach a maximum incidence in later life; these causes include cardiovascular disease. However, the health system also plays an important role by providing preventive and acute phase treatment that can effectively delay death from cardiovascular disease.

CONCLUSIONSThe decrease in cardiovascular mortality had an undeniable impact on the increase in LE at birth among the Spanish population during the period 1980-2009. Furthermore, among the ≥65-year-old age group, there has been a clear decrease in mortality from cerebrovascular diseases and other heart diseases, and a slight decrease in IHD mortality.

FUNDINGThis study was partly conducted with the project “Changes in longevity, aging, and old age in Spain. From 50 to 100 and over. The present and future.” (CSO2010-18925) within the National Plan for R+D+i of the Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTNone declared.

We would like to thank Professor Wilma Nusselder (Department of Public Health, Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam, The Netherlands) for providing the programming syntax for the R statistical software package for the decomposition of LE by age and cause of death.