Over the last decade, there has been an exponential increase in the use of clinical simulation as a training tool for health professionals. This increase is due to simulation being more effective in learning to make clinical decisions, acquiring technical skills, and working in teams than traditional teaching methods.1,2 In addition, the acquired skills are transferred to the work environment, which translates into improved clinical outcomes without compromising patients and health professionals.3

A key element of this learning method is debriefing, which has been defined as a conversation between several people to review a real or simulated event, in which the participants analyze their actions and reflect on the role of thought processes, psychomotor skills, and emotional states to improve or maintain future performance. Although experience is the basis for adult learning, Kolb's learning theory suggests that this learning process cannot take place without rigorous reflection on the part of learners such that they are enabled to examine the values, assumptions, and knowledge bases that guide the actions of health professionals. That is, gaining experience is not equivalent to becoming an expert.4

Despite its importance, debriefing is a dilemma for many instructors because they often cannot find ways to openly express their critical judgments about observed clinical performance without hurting their colleagues’ feelings or making them defensive. As a result, instructors often fail to verbalize their thoughts and feelings to avoid confronting, challenging, or provoking negative emotions in their colleagues with the aim of maintaining a good working relationship with them.5 This feedback dilemma is resolved by helping the professional to elicit the highest standards of performance from the trainees while holding them in the highest personal regard.6

This article reviews the principles of conducting effective debriefing and describes different debriefing styles and the “debriefing with good judgment” approach, which represents an attempt to solve this dilemma.

DEBRIEFING STYLESHealth professionals do not passively perceive an objective reality, but integrate all the data pertinent to a given clinical case. Their active thought process allows them to filter, create and apply meaning to their lived experiences. Thus, a clinical outcome is a consequence of the actions taken which, in turn, are the result of the thought processes used by health professionals to interpret the situation (their frames).

It could be ineffective to analyze clinical outcomes solely on the basis of actions taken, because this approach would fail to identify the reasons for acting in a particular way. However, future performance can be improved by revealing the frames that explain the actions taken. Just as a diagnosis must be established before treating a disease, the reason for taking a clinical action must also be determined (ie, the underlying frames) in order to teach and discuss how it can be improved or maintained in the future.

Although it may seem obvious that debriefing could be improved by revealing the trainee's frames, the importance of identifying and revealing the instructor's frames is less obvious. For debriefing to be efficient and nonthreatening, instructors must be able to reveal and examine their own frames that they use to interpret the observed clinical situation. Without this ability, it is very difficult for instructors to understand the trainees’ frames. There are two reasons for this: firstly, instructors should use their own clinical experience to explain the frames and actions they would have respectively used and taken in a similar simulation. They should also be able to share this valuable information with trainees. Secondly, they must be willing to discuss with the trainees the validity of their own frames for interpreting clinical performance.7 We describe this process by analyzing and comparing the frames used by instructors when they use different approaches to debriefing: judgmental, nonjudgmental, and with good judgment (Table 1).

Comparison of Judgmental, Nonjudgmental, and Good Judgment Approaches to Debriefing

| Judgmental | Nonjudgmental | With Good Judgment | |

|---|---|---|---|

| The effective instructor | Helps the trainees to change; tells the trainees what they did wrong | Helps the trainees by asking questions that help them see what they did wrong | Creates a context for learning and change |

| Main focus of debriefing | External: the actions/inactions of the trainee | External: the actions/inactions of the trainee | Internal: the meanings and assumptions of both the instructor and trainee |

| How do you see the trainee? | A person who takes actions and makes mistakes | A person who takes actions and makes mistakes | A person whose actions are the result of assumptions, knowledge, and specific attitudes |

| Who knows the truth about the situation? | The instructor | The instructor | Both the instructor and trainee have their perspective |

| Who does not understand? | The participant | The participant | The instructor |

| Attitude toward self and the trainee | “I, the instructor, I will set you straight”“I’m right,” or “You’re wrong” | “I, the instructor, will find the friendliest way to tell how to do it well”“I’m right” or “You’re wrong,” but “I don’t want you to get defensive, so how do I get tell you the bad news and get you to change in a friendly way?” | “I see what you are or are not doing and, given my perspective, I don’t understand”Genuine confusion and inquiry in order to understand the meaning of the trainee's actionsRespect for self (“I have an opinion of what happened that makes me think that there were some problems...”)Respect for the trainee (“You are also capable, are trying to do your best, and have your own view of what happened...”)“I’ll deal with this as a genuine problem to solve and will inquire how to fix it” (we both can learn something that makes us change) |

| The focus of the instructor's words | “I’m teaching you”“I’m going to tell you how it's done” | “I’m teaching you”“I’m going to tell you how it's done” | “Help me understand why you...” |

Adapted from Rudolph et al5 with permission.

Imagine an instructor disdainfully asking a group of trainees “Can anyone tell me what went wrong?”. The judgmental approach, whether gently applied or mixed with harsh criticism, puts truth in the possession of the instructor alone, error in the hands of the trainee, and assumes that there is an essential flaw in the trainee's thinking or actions. This style can have significant costs: humiliation, reduced motivation, or reluctance to raise issues related to other areas. However, the shame-and-blame approach has one advantage: the trainee is rarely left in doubt about the instructor's standpoint regarding the main issues.

Characteristics of a Nonjudgmental Approach to DebriefingThe main dilemma facing instructors who want to move on from the judgmental approach is how to deliver a critical message, avoid negative emotions and defensiveness, and preserve professional identity. The dilemma is often solved by the use of protective social strategies, such as sugar-coating errors, sandwiching criticism between two compliments, skirting around charged issues, or completely avoiding the subject. Many instructors, including ourselves, have used the Socratic approach in which leading questions are asked using a friendly tone of voice to lead the trainee to the critical insight held by the instructor but who is reluctant to explicitly communicate (facilitation).

Although the nonjudgmental approach has the advantage of avoiding direct blaming and the hurt and humiliation of the judgmental style, it has a serious weakness. Contrary to expectations, when the instructors do not give their opinions and use open questions or the Socratic method to camouflage their judgments, the trainee often feels confused about the nature of the question or suspicious of the instructor's unclear motives (“What have I done that the instructor isn’t telling me about?”). Despite the desire to appear nonjudgmental, the implicit opinion of the instructor often appears through subtle cues, such as facial expression, tone and cadence of voice, or body language. Thus, it is clear that this approach is not really nonjudgmental. Although the tone of the debriefing may seem softer, the underlying frame of the instructor is the same as before: “I’m right, I have the full picture, and my job is to hand over the correct knowledge and behavior to you, the trainee.” Although the judgmental approach often directly humiliates the trainee, the nonjudgmental approach may also have the same effect and even have other negative effects. The trainee may be left thinking that the mistake is so serious that the instructor is avoiding talking about it. Even worse, this style can discourage discussing mistakes, which is exactly the opposite of the aim of simulation and debriefing. What has to be developed is a climate in which mistakes are riddles or puzzles to solve in groups rather than errors to be covered up.8

Characteristics of Debriefing With a Good Judgment ApproachThis approach is based on the open sharing of opinions or personal points of view and assumes that the trainees are doing their best. It demands the highest standards from the trainees (or colleagues) and assumes that their responses deserve great respect. For example, if the simulation center's mission is to transform mistakes into sources of learning to improve patient safety, it is inappropriate for instructors to cover them up and to shy away from discussing them, and to avoid expressing their own opinion or to ask open or leading questions in the hope that the trainees can reach the conclusions that instructors are reluctant to express. If mistakes cannot be analyzed and discussed in a simulation center, how can other people be expected to discuss them in the clinical setting? To promote patient safety, a way is needed to openly discuss mistakes. Thus, the debriefing approach called “with good judgment” was developed; the name itself highlights the need for instructors to discover their own good judgment. This style allows trainees to make and discuss mistakes while feeling valued and capable. It also allows instructors to show their expertise and offer constructive criticism, such that trainees and instructors are able to merge their own experience with the new knowledge due to the creation of a meaningful learning environment.9

Transparent Talk in Debriefing: The Good Judgment Approach With Advocacy-inquiryWe present a case example: a trainee cardiologist is called to the radiology department because a patient hospitalized for bilateral pneumonia and stable angina has undergone a decrease in their level of consciousness while undergoing chest X-ray. When the trainee arrives, the patient does not respond to stimuli and has marked labial cyanosis, shallow breathing, and a radial pulse of 100 bpm. The trainee immediately requests a resuscitation bag and face mask. The apparatus is not available in the room and while it is being located the patient goes into respiratory arrest. Once again the trainee requests the apparatus and, after a few minutes of waiting while the room is searched, again checks the pulse, which has now decreased to 30 bpm.

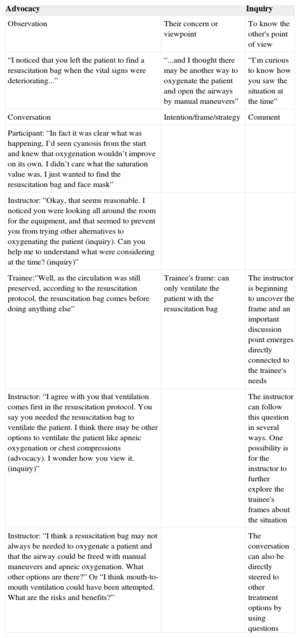

This case example represents a clinical simulation for training in emergency situations. Following the simulation, a cardiologist trained as a simulation instructor conducts a debriefing. The cardiologist helps the trainee to explore and reveal the frames that led to nonventilation and extreme bradycardia in order to improve their performance in similar situations in the future. As frames are invisible, the only way they can be identified is to help the trainees to describe them, based on their actions and the observed results. Pairing advocacy with inquiry is a particularly effective style of debriefing speech. Advocacy can be implemented by assertion, observation, or statement. Ideal advocacy combines the actions (or inactions) observed by the instructor (“I observe that...”) with good judgment about their clinical consequences (“I think that...”). Inquiry is shown by an attitude of genuine curiosity that leads the trainees to reflect on and share the frames that underlay their actions (“I ask myself...”). Table 2 shows the process followed by the instructor to uncover the trainees’ frames.

Advocacy and Inquiry: Debriefing Style to Elicit the Frames That Guide Clinical Actions

| Advocacy | Inquiry | |

|---|---|---|

| Observation | Their concern or viewpoint | To know the other's point of view |

| “I noticed that you left the patient to find a resuscitation bag when the vital signs were deteriorating...” | “...and I thought there may be another way to oxygenate the patient and open the airways by manual maneuvers” | “I’m curious to know how you saw the situation at the time” |

| Conversation | Intention/frame/strategy | Comment |

| Participant: “In fact it was clear what was happening, I’d seen cyanosis from the start and knew that oxygenation wouldn’t improve on its own. I didn’t care what the saturation value was, I just wanted to find the resuscitation bag and face mask” | ||

| Instructor: “Okay, that seems reasonable. I noticed you were looking all around the room for the equipment, and that seemed to prevent you from trying other alternatives to oxygenating the patient (inquiry). Can you help me to understand what were considering at the time? (inquiry)” | ||

| Trainee:“Well, as the circulation was still preserved, according to the resuscitation protocol, the resuscitation bag comes before doing anything else” | Trainee's frame: can only ventilate the patient with the resuscitation bag | The instructor is beginning to uncover the frame and an important discussion point emerges directly connected to the trainee's needs |

| Instructor: “I agree with you that ventilation comes first in the resuscitation protocol. You say you needed the resuscitation bag to ventilate the patient. I think there may be other options to ventilate the patient like apneic oxygenation or chest compressions (advocacy). I wonder how you view it. (inquiry)” | The instructor can follow this question in several ways. One possibility is for the instructor to further explore the trainee's frames about the situation | |

| Instructor: “I think a resuscitation bag may not always be needed to oxygenate a patient and that the airway could be freed with manual maneuvers and apneic oxygenation. What other options are there?” Or “I think mouth-to-mouth ventilation could have been attempted. What are the risks and benefits?” | The conversation can also be directly steered to other treatment options by using questions |

The debriefing style shown in Table 2 can be contrasted with a judgmental version (“I can’t believe it took you so long to realize the patient was desaturating!”) or with a nonjudgmental version, that is, one in which the participant has to guess what the instructor is thinking (“How was the patient's respiration when you went to find the apparatus?” or “Do you think something can be improved?”). Although the judgmental version clearly and directly expresses the instructor's point, the trainee does not learn what frames led to the specific course of action and the trainee could even feel humiliated. The nonjudgmental version leaves the trainee uncertain about what the instructor thinks and also considerably extends the debriefing time, since the trainee does not know the reason for the question. The final result can easily be one of confusion and even defensiveness. The trainee may correctly detect that the instructor already knows the answer to the question and has a hidden perspective (or judgment). This approach contrasts with advocacy-inquiry discourse, which directly and clearly states the instructor's perspective and concerns, and establishes the context for understanding the thought processes that focused the trainee on finding the apparatus. This technique does not consist in making polite conversation, but places the instructor's thoughts, judgments, and feelings at the center of the action. This is an example of how to help trainees to achieve the highest standards of performance, while holding them in the greatest regard.

The with-good-judgment style shifts the focus of debriefing in several ways. On the one hand, it focuses on creating a learning environment for adults (including the instructor) in which they can learn important lessons that will help them to achieve goals. Furthermore, the focus is widened to not only include the trainees’ actions, but also the systems they use to make sense of the actions (frames). Furthermore, to make sense of the action, the instructor's frames also form part of the debriefing and are tested and explored with trainees.10

However, debriefing with good judgment has some limitations. Firstly, the approach assumes that trainees are acting in good faith and are trying to do their best. Secondly, when conducted in cultures in which deference to authority or senior staff is the norm, trainees may be inhibited and may not disclose their own views because they could seem to contradict the views of those with greater authority. The approach can be supported in this setting by explicitly preparing the norms and aims of the simulation, although even this is sometimes insufficient.

DEBRIEFING AS FORMATIVE ASSESSMENTDebriefing is an effective strategy for formative assessment (during learning) and professional development. Inquiry is used to reveal the frames that explain the difference between the expected and the observed clinical performance (which may be positive or negative). It enables specific feedback to be given that is adapted to the trainees’ individual needs and helps them to develop new frames that will allow them to develop new and more effective actions in similar clinical situations in the future.11

In the example provided, the trainee only thought of ventilating the patient with the resuscitation bag and face mask. Debriefing would help the intern discover the reasons for this and teaching or discussion would be adapted to his or her specific frame. The trainee may not have considered alternatives such as apneic oxygenation or chest compression, due to lack of knowledge, or could have lost focus on the situation due to being so concerned with finding the apparatus. This formative assessment is based on the instructors having specific predetermined learning objectives and having the ability to specifically describe the actions and the expected and observed results.12

CONCLUSIONSThe debriefing with good judgment approach can reveal thinking processes understood as the reasons for having acted in a certain way and can maintain or improve clinical performance in the future.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTNone declared. Both authors work in nonprofit institutions dedicated to improving healthcare quality and patient safety by training medical teams using clinical simulation.