According to the Cochrane organization, improving precision is one of the main objectives of meta-analyses.1 Effectively, most studies that do not demonstrate statistically significant differences are only useful for recommending that a larger study—with the power to observe such differences—be carried out. Given the difficulty of obtaining a large enough sample size, meta-analyses represent a free, simple way to reduce the effect of random sampling.

Two fundamental dangers cast a shadow on this interesting approach: heterogeneity, or inconsistency, and publication bias. The first, meaning the possibility that the studies are so different that calculating a simple mean is not appropriate, is a limitation faced by any research group working on this arduous task. A meta-analysis with high levels of inconsistency makes certain undesirable courses of action necessary. One option is to cancel the analysis, as, ultimately, one should not calculate a mean from studies that are fundamentally different. Another option is to investigate the reasons for these differences and focus the project on these, something which is always difficult and, at times, impossible, particularly when the number of studies is small.1 Unlike individual studies, where the sample size required to reach the study objectives can be planned in the initial stages, authors conducting a meta-analysis are faced with this reality in the later stages, those of data analysis.

We recently read a meta-analysis by Verdoia et al.2 in Revista Española de Cardiología, in which the authors compared a short duration of dual antiplatelet therapy (1-3 months) with the standard 1-year duration following percutaneous coronary intervention. The primary efficacy endpoint was mortality at 12 months, and the safety endpoint was the rate of major bleeding complications. The authors concluded that the short treatment course reduced major bleeding without affecting survival. As survival was not affected, the lower bleeding rate led to the conclusion that a short course was preferable, lending weight and relevance to the study.

The authors specifically mentioned that they did not find significant heterogeneity for either of the 2 endpoints: safety and efficacy. Our first reflection is on the safety analysis, or rate of major bleeding. Figure 3 of the article showed an I2=66%. According to this test, 66% of the variability observed between the studies can be attributed to heterogeneity, rather than to chance. According to Cochrane, an I2 of between 50% and 90% represents substantial heterogeneity.1 Consistently, the P value for the assessment of heterogeneity was .02; this figure gains relevance when compared with the limit set by the authors of the article as the level for significant heterogeneity (P<.1). This suggests that the effect of the short treatment course on the rate of bleeding depends on circumstances that are as yet not established: in some conditions it may have a beneficial effect, but not so in others.

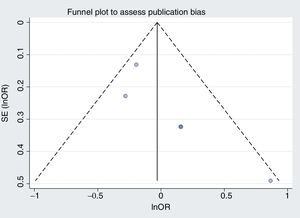

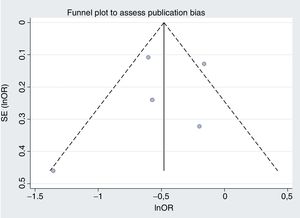

Our second reflection is on publication bias, the second danger of meta-analysis. This bias was assessed using funnel plots to look for asymmetry in the odds ratios and sample sizes. The aim of this was to detect the possibility of the small studies giving different results from the large studies. If this bias were present, a random effects model would enhance its impact.1 The figures are not shown in the article, but if we draw up mortality and bleeding, the difficulty in visually assessing asymmetry with 5 studies becomes obvious (figure 1 and figure 2, respectively). Figure 1 appears asymmetrical and would suggest that, compared with the large studies, the small studies showed a benefit with the longer treatment duration. If we calculate Egger and Begg tests, they show P=.07 and P=.09, respectively, values that are significant if we use the usual limit of .1.

In summary, we wonder whether this meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials (highest level of evidence) has provided new information and improved precision or has been compromised by the dangers inherent to this type of analysis.

FUNDINGNone.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONSD. Hernández-Vaquero: analysis and interpretation. R. Díaz: concept and writing. P. Avanzas: critical review. A. Domínguez-Rodríguez: concept and critical review.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTNone.