Data on implants of cardiac pacing systems in Spain in 2023 are presented.

MethodsThe registry is based on the information provided by centers to the recording platform of the Heart Rhythm Association after device implantations, through Cardiodispositivos, the online platform of the National Registry. Other information sources include: a) data transfers from the manufacturing and marketing industry; b) the European pacemaker patient card; and c) local databases submitted by the implanting centers.

ResultsIn 2023, 112 hospitals participated in the registry (30 more than in 2022). A total of 24 343 device implantations were reported (48.1% more than in 2022) compared with 45 120 reported by Eucomed (European Confederation of Medical Suppliers Associations). Of these, 1646 were cardiac resynchronization therapy pacemakers. The devices showing the largest increases were leadless pacemakers, with 963 devices implanted, representing an 18.1% increase over 2022. The most frequent indication was atrioventricular block followed, for the first time, by atrial tachyarrhythmia with slow ventricular response. The number of devices included in remote monitoring also increased (cardiac resynchronization therapy defibrillators, 71%; cardiac resynchronization therapy pacemakers, 63%; and conventional pacemakers, 28%), although more moderately.

ConclusionsIn 2023, there was an increase in the number of institutions participating in the registry. The reporting of device implantations rose by 48.1%, and the implantation of leadless pacemakers grew by 18.1%. Remote monitoring also experienced modest growth compared with previous years.

Keywords

The current report presents data submitted by Spanish hospitals on cardiac pacing activity for 2023. The report includes demographic data, pacemaker types and numbers, indications, pacing modes, and the characteristics of the material implanted. In addition, we compare the data with that from previous years1–8 and with European data provided by Eucomed (European Confederation of Medical Suppliers Association).9 Data on remote monitoring are also presented.

METHODSThe registry is based on information voluntarily provided by participating centers and manufacturers after device implantation, covering first implants and replacements. The registry is continuously compiled, updated, and maintained throughout the year by a team comprising full members of the Heart Rhythm Association of the Spanish Society of Cardiology (SEC) and by the technical team and coordinator of the Heart Rhythm Association registries of the SEC. The device manufacturing and marketing industry also collaborate by transferring of relevant data. All members have contributed to data cleaning and analysis and are responsible for this publication.

In addition, in accordance with Spanish legislation SCO/3603/2003,10 of December 18, and SSI/2443/2014,11 of December 17, 2 partially automated files were created: the “National pacemaker registry” and the “National implantable cardioverter-defibrillator registry”. CardioDispositivos12 is the online platform of the these 2 registries, which are owned by the Spanish Agency for Medicines and Health Products, Ministry of Health, Spanish Government, and have been managed by the SEC since 2016. Article 36 of Royal Decree 192/2023, of March 21,13 states that health care centers and professionals are obligated to report specific data on pacemaker and defibrillator implantation (Article 18 of Regulation [EU] 2017/745 of the European Parliament)14 to the abovementioned registries. In 2023, and up to the date of drafting this report, 15 564 implants have been reported via this route. This figure represents 64% of all implants reported to the recording platform of the Heart Rhythm Association of the SEC. Other information sources include: a) data transfer from the manufacturing and marketing industry; b) the European Pacemaker Patient Identification Card (EPPIC); and c) local databases submitted by implanting centers. Remote monitoring data are entirely obtained from the manufacturers.

Census data for the calculation of rates per million population, both nationally and by autonomous community and province, were obtained from the Spanish National Institute of Statistics and refer to the first trimester of 2023.15 For population rates, implantation and remote monitoring data were obtained from the manufacturers’ billing data for 2023. As in previous years, the data from the present registry were compared with those provided by Eucomed.9 The percentages of each variable analyzed were calculated based on the total number of implants with available information on the parameter.

The present work has been conducted in accordance with international recommendations on clinical research (Declaration of Helsinki of the World Medical Association).

Statistical analysisResults are expressed as the mean or median [interquartile range], depending on the distribution of the variable. Continuous quantitative variables were analyzed using analysis of variance or the Kruskal-Wallis test, while qualitative variables were analyzed using the chi-square test.

RESULTSData submitted to the registry and sample qualityIn 2023, 24 343 implants were reported to the recording platform of the Heart Rhythm Association of the SEC (48.1% more than in 2022). This figure includes single-chamber and dual-chamber pacemakers (conventional), pacemakers with cardiac resynchronization therapy, and leadless pacemakers. Of these, 15 564 were reported by direct entry of data into the CardioDispositivos platform,12 6153 via EPPICs submitted to the SEC, and the remainder via other information sources (eg, the local databases of implanting centers). In total, 112 hospitals voluntarily participated in the present registry (30 more than in 2022) (table 1).

Public and private hospitals submitting data to the Spanish Pacemaker Registry in 2023

| Autonomous community/center |

|---|

| Andalusia |

| Área de Gestión Sanitaria Este de Málaga-Axarquía |

| Hospital Costa del Sol |

| Hospital HLA Inmaculada de Granada |

| Hospital de La Serranía |

| Hospital Universitario de Jaén |

| Hospital Universitario Juan Ramón Jiménez |

| Hospital Universitario Punta de Europa |

| Hospital Universitario Reina Sofía de Córdoba |

| Hospital Universitario San Cecilio |

| Hospital Universitario Virgen de las Nieves |

| Hospital Universitario Virgen del Rocío |

| Hospital Universitario Virgen de Valme |

| Hospital Universitario Virgen de la Victoria |

| Hospital Vithas Granada |

| Hospital Vithas Virgen del Mar |

| Aragon |

| Hospital General San Jorge |

| Hospital Obispo Polanco |

| Hospital Universitario Miguel Servet |

| Hospital Viamed Montecanal |

| Principality of Asturias |

| Fundación Hospital de Jove |

| Hospital Universitario de Cabueñes |

| Hospital Universitario San Agustín |

| Balearic Islands |

| Clínica Juaneda Menorca |

| Hospital de Manacor |

| Hospital Universitario Son Espases |

| Canary Islands |

| Hospital Universitario de Gran Canaria Dr. Negrín |

| Hospital Universitario de Canarias |

| Hospital General de La Palma |

| Hospital Universitario Nuestra Señora de Candelaria |

| Cantabria |

| Hospital Universitario Marqués de Valdecilla |

| Castile and León |

| Complejo Asistencial Universitario de León |

| Complejo Asistencial Universitario de Palencia |

| Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valladolid |

| Hospital Nuestra Sra. de Sonsoles |

| Hospital Universitario de Burgos |

| Hospital Universitario Río Hortega |

| Hospital Universitario de Salamanca |

| Hospital Virgen de La Concha |

| Castile-La Mancha |

| Hospital General Universitario de Albacete |

| Hospital General Universitario de Ciudad Real |

| Hospital General Virgen de la Luz |

| Hospital Nuestra Señora del Prado |

| Hospital Universitario de Toledo |

| Hospital QuirónSalud de Albacete |

| Catalonia |

| Clínica Mi Novaliança |

| Hospital Clínic de Barcelona |

| Hospital del Mar |

| Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau |

| Hospital de Terrassa |

| Hospital de Tortosa Verge de la Cinta |

| Hospital del Vendrell |

| Hospital Universitario Arnau de Vilanova |

| Hospital Universitario de Bellvitge |

| Hospital Universitario Germans Trias i Pujol |

| Hospital Universitario de Girona Dr. Josep Trueta |

| Hospital Universitario Joan XXIII de Tarragona |

| Hospital Universitario Mútua de Terrassa |

| Hospital Universitario Parc Taulí |

| Hospital Universitari Vall d’Hebron |

| Parc Sanitari Sant Joan de Déu |

| Valencian Community |

| Hospital Arnau de Vilanova de Valencia |

| Hospital Clínica Benidorm |

| Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valencia |

| Hospital Francesc de Borja |

| Hospital General Universitario Dr. Balmis |

| Hospital General Universitario de Castelló |

| Hospital General Universitario de Valencia |

| Hospital HLA Vistahermosa |

| Hospital Imed Levante |

| Hospital de Manises |

| Hospital Marina Salud de Denia |

| Hospital Universitario y Politécnico La Fe |

| Hospital Universitario de San Juan de Alicante |

| Hospital Universitario del Vinalopó |

| Extremadura |

| Hospital Universitario de Badajoz (Infanta Cristina) |

| Hospital Universitario de Cáceres |

| Hospital Comarcal de Zafra |

| Galicia |

| Hospital Universitario Lucus Augusti |

| Complexo Hospitalario Universitario A Coruña |

| Hospital Montecelo |

| Hospital Álvaro Cunqueiro |

| Madrid |

| Clínica Universidad de Navarra Madrid |

| Hospital Central de La Defensa Gómez Ulla |

| Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón |

| Hospital HM Madrid |

| Hospital HM Montepríncipe |

| Hospital HM Puerta del Sur Madrid |

| Hospital HM Sanchinarro |

| Hospital Universitario Clínico San Carlos |

| Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre |

| Hospital Universitario de Fuenlabrada |

| Hospital Universitario Fundación Alcorcón |

| Hospital Universitario de Getafe |

| Hospital Universitario del Henares |

| Hospital Universitario Infanta Elena |

| Hospital Universitario Príncipe De Asturias |

| Hospital Universitario Puerta de Hierro-Majadahonda |

| Hospital Universitario de Torrejón |

| Region of Murcia |

| Hospital General Universitario Los Arcos del Mar Menor |

| Hospital General Universitario J.M. Morales Meseguer |

| Hospital General Universitario Rafael Méndez |

| Hospital General Universitario Santa Lucía de Cartagena |

| Hospital HLA La Vega |

| Chartered Community of Navarre |

| Clínica Universidad de Navarra |

| Complejo Hospitalario de Navarra |

| La Rioja |

| Hospital Viamed Los Manzanos |

| Hospital San Pedro |

| Basque Country |

| Hospital de Basurto |

| Hospital Universitario Araba |

| Hospital Universitario de Cruces |

| Hospital Universitario Donostia |

| Hospital Universitario de Galdakao |

Compared with the 2023 billing data from all manufacturers (42 848 implants in Spain), the total number of implants reported to the recording platform of the Heart Rhythm Association of the SEC represented 56.8% of all implant activity in Spain (16 percentage points higher than in 2022).

Missing data for the various variables analyzed were excluded from the statistical analysis. Their distribution was heterogeneous among variables but generally strongly affected the representativeness of the data. In summary, the percentages of missing data for each variable were 8.3% for age, 11.3% for sex, 97% for symptoms, 78% for etiology, 68% for preimplantation electrocardiogram, and 68.5%, 66.2%, and 21.2% for lead position, access route, and lead fixation, respectively. In addition, 76.3% of data were missing for magnetic resonance compatibility and 90% for the reason for generator explantation.

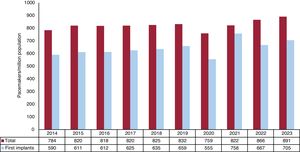

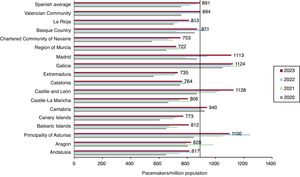

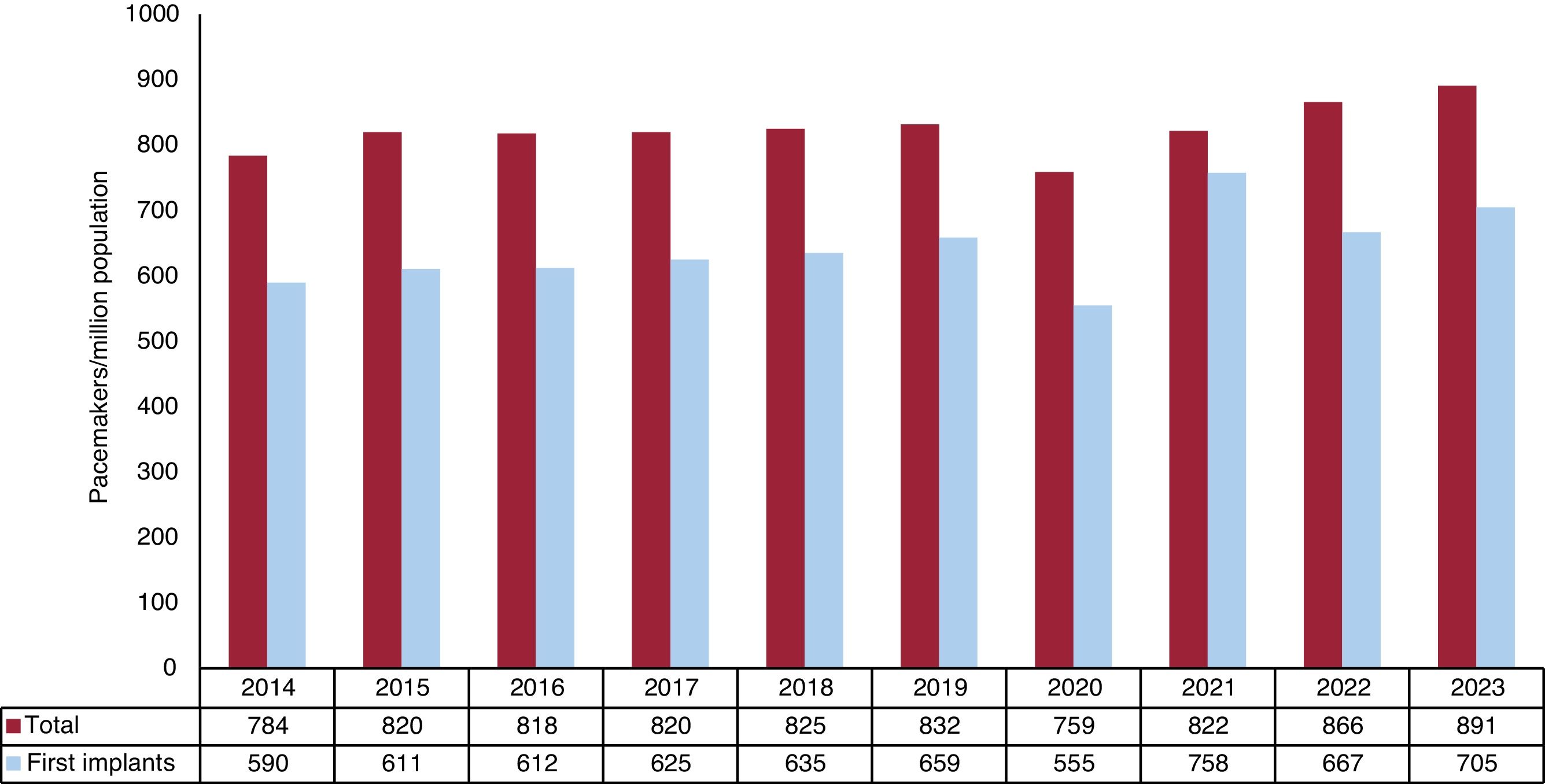

Conventional pacemakersAccording to the billing data from the manufacturing and marketing industry, 42 848 conventional pacemakers were implanted in Spain in 2023. Because the Spanish population on January 1, 2023, comprised 48 085 361 individuals, according to the National Institute of Statistics,15 the implantation rate was 891 units/million population (figure 1). In 2023, 4 autonomous communities exceeded 1000 units/million population: Castile and León, Galicia, Madrid, and Asturias (1126, 1124, 1113, and 1100 units/million, respectively). The autonomous cities of Ceuta and Melilla implanted about 100 units/million population while Murcia was the autonomous community with the lowest implantation rate, at 722 units/million population (figure 2).

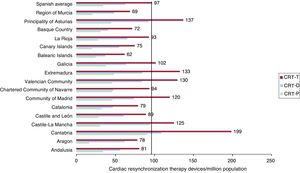

In 2023, 4669 cardiac resynchronization therapy devices were implanted, comprising 3023 CRT with defibrillation (CRT-D) devices and 1646 CRT without defibrillation (CRT-P) devices. The rates of total resynchronization (CRT-T), CRT-D, and CRT-P devices were 97, 63, and 34 units/million population, respectively. Regarding the distribution by autonomous community, the implantation rates of cardiac resynchronization devices were highest in Cantabria, at 199 units/million population, followed by Asturias and Extremadura, at 137 and 133, respectively. The Balearic Islands and Murcia, at 62 and 69 units/million population, had the lowest rates of cardiac resynchronization device implants. For CRT-P devices, Cantabria once again headed the list, at 90 units/million population, followed by Extremadura and Asturias, at 52 and 50 units/million, respectively. Aragon had the lowest number of CRT-P implants, at 16 units/million population (figure 3).

Cardiac resynchronization therapy devices per million population in 2023, national average and by autonomous community. CRT-D, cardiac resynchronization therapy with defibrillation; CRT-P, cardiac resynchronization therapy without defibrillation; CRT-T, total cardiac resynchronization therapy.

In 2023, 963 leadless pacemakers were implanted in Spain; 27% of these were capable of maintaining atrioventricular (AV) synchrony (figure 1 of the supplementary data). Since September 2023, some autonomous communities have been able to implant single-chamber devices from a second manufacturer. In absolute numbers, Catalonia had the highest number of such implants (233 units), followed by Madrid and the Basque Country. With 168 and 134 units, respectively (figure 4). However, after adjustment for population, the communities with the highest implantation rates per million population were the Basque Country and Galicia (figure 2 of the supplementary data). Aragon and Extremadura did not implant any devices of this type.

Demographic and clinical dataThe mean age of the patients at implantation was 77.8 years. The mean age was slightly higher for women than for men (79 vs 77 years) and for replacements vs first implants (80 vs 77.5 years). Men predominated in pacemaker implantation (60%), both for first implants (61.2% vs 38.8%) and replacements (57.2% vs 42.8%). The main reason for pacemaker implantation was syncope (40%), followed by dizziness (22%) and heart failure (16%). Less common reasons were prophylactic implantation (8.4%) and asthenia (5%). The most common cause of a conduction disorder was conduction system fibrosis related to advanced age (80%), followed by iatrogenic causes (5%, surgery; 2%, transcatheter aortic valve implantation; 1%, ablation).

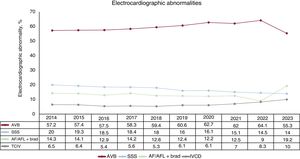

The most frequent preimplantation electrocardiographic abnormality was AV block (AVB) (55.3%). Of these, third-degree AVB predominated, accounting for 41% of procedures, followed by second-degree AVB, at 15.9%. Atrial fibrillation (AF) with complete heart block was reported in 5.5% of implants while sick sinus syndrome (SSS) represented 14%. AF with slow ventricular response accounted for 19.2% of implants. Intraventricular conduction defect was reported in 10% of cases (figure 5).

Type of procedureSimilar to 2022, 76.6% of reported procedures were first implants and 23.4% were replacements. Of the replacements, 95.9% involved the implantation of a new generator. The most frequently used access route continued to be the subclavian vein (50.5%), closely followed by axillary access (46.5%).

The most frequent reasons for generator explantation were end-of-life battery depletion (84%) and infections (2.2%). In addition, 2% of replacements were due to device dysfunction. The most frequent reasons for lead explantation were infection (44.7%), followed by displacement (17.4%) and dysfunction (10.4%).

Lead typeMost leads used, both in the atrium and the ventricle, were bipolar (98.3% in the atrium and 97.7% in the ventricle) and had active fixation (94.7% and 91.2%, respectively). Active-fixation leads (64.7%) and bipolar leads (50.5%) predominated in the tributary veins of the coronary sinus, followed closely by quadripolar leads (46.4%). No differences by sex were found in the choice of lead type but there was significantly greater use of passive fixation in patients older than 80% years (6.8% vs 4.5% in the atrium [P=.002] and 12% vs 5.4% in the ventricles [P < .001]).

A lead was implanted in the right atrium (preferentially in the atrial appendage; other locations were rare or not specified) in 47.7% of procedures, in the right ventricle in 74.5%, and in the left ventricle in 5.1%. Epicardial implants were rare in the atrium (0.3%) and right ventricle (0.6%) but were more frequent in the left ventricle (11.4%). The most frequent location in the right ventricle was once again the apex (49.1%), followed by conduction system pacing (CSP), which continued its increase (19.3%). There was a corresponding significant decrease in implants in the outflow tract/septum, which fell to 17.5% in 2023 (from 27.8% in 2022).

Most of the implanted leads were compatible with magnetic resonance (99% of atrial leads, 98.4% of right ventricular leads, and 95.4% of left ventricular leads), while 96% of generators were magnetic resonance-compatible. However, the use of such leads was significantly lower in patients older than 80 years (94.7% vs 97.7%; P < .001).

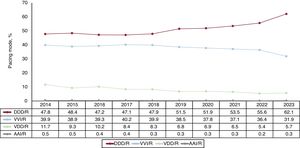

Pacing modesThe use of generators with built-in activity sensors is now widespread. Sequential dual-chamber DDD/R pacing continued its upward trend from previous years, increasing by almost 7 percentage points (62.1% vs 55.6% in 2022), at the expense of both VDD pacing and single-chamber ventricular pacing. Indeed, this pacing mode represented 63% of first implants and 58.8% of replacements. The use of VDD/R systems continued to be uncommon, particularly for first implants. These systems represented just 4.2% of all pacemakers, similar to 2022 (5.7%) due to replacements (10.7%). Single-chamber ventricular pacing also continued the marked decline in recent years, with an almost 5 percentage point reduction (37.1% in 2021, 36.4% in 2022, and 31.9% in 2023). Isolated atrial pacing (AAI/R) continued to be rare (9 first implants and 24 replacements). Figure 6 shows the trends in pacing modes.

Differences by sex persisted, with DDD pacing used in 64.4% of men vs 59.1% of women. This difference lessened in patients older than 80 years (50% of men vs 48.4% of women) and was more marked in younger patients (77.4% vs 73.8%, P < .001).

Pacing mode selectionIn this section, we review the selection of different pacing modes and the degree of adherence to the recommendations in current clinical practice guidelines.16 We also analyze the influence of various demographic factors on the selection. As in previous registries, and to maintain the uniformity of the data and better evaluate adherence in pacing mode selection, we must make some clarifications:

- •

Patients with AVB and permanent atrial tachyarrhythmia (EPPIC code C8) have been excluded from the AVB subsection.

- •

The intraventricular conduction defect subsection includes highly variable indications (ranging from complete block of the different branches to alternating bundle branch block).

- •

For SSS, we have differentiated between patients in AF or permanent atrial tachyarrhythmia with associated bradycardia and those in sinus rhythm.

With the aim of maintaining AV synchrony, the use of sequential pacing has increased (69.3% vs 74.7%). VDD/R mode remained stable (5.1%). Overall, the use of modes maintaining AV synchrony reached 79.9%.

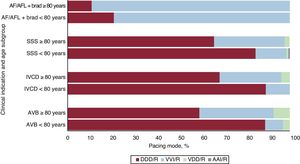

The influence of demographic factors such as age and sex on the selection of pacing modes capable of maintaining AV synchrony is well-known. AV synchrony was maintained in 92% of patients younger than 80 years vs 66.6% of older patients. This figure represents an increase from previous years (57.7% in 2022 and 64.3% in 2021). The use of VDD/R devices was stable (3.1% in patients younger than 80 years vs 7.3% in octogenarians). Figure 7 shows the distribution of pacing modes by clinical indication and age.

Although differences between men and women were also detected (AV synchrony maintenance was attempted in 82.3% of men vs 75% of women), this disparity was even more pronounced at advanced ages. For example, DDD/R pacing was used in 63.2% of men older than 80 years vs only 54.6% of women. VDD/R pacing was similar in both sexes among patients younger than 80 years of age (3%) but was 6.3% in male octogenarians and 8.4% in female octogenarians.

Analysis of pacing mode by the degree of AVB revealed that sequential dual-chamber pacing was used in 87.3% of patients with first-degree AVB, in 84.6% of those with second-degree AVB, and in 76.5% of those with complete AVB. VDD pacing was very similar among the different AVB degrees (ranging between 5.3% and 6.3%). In 2022, the use of VVI/R devices in AV conduction disorders fell to 20.1%, although their use increased in female octogenarians to 37%.

Intraventricular conduction defectsFor intraventricular conduction defects, devices capable of maintaining AV synchrony exhibited a notable increase (81.4% overall). DDD/R pacing increased from 66.3% in 2022 to 79.6% in 2023. This pacing mode was slightly less commonly used in men (77.9% vs 82.4%). In octogenarians, DDD/R pacing was also the most commonly used pacing mode but its use dropped from 89.2% in patients younger than 80 years to 68.4% in older patients. All VDD/R devices were implanted in patients older than 80 years, although the percentage was small (3.8%). CRT-P devices represented 14.5% of implants for this indication, with no differences by age (12.7% in octogenarians and 13% in patients younger than 80) but were slightly more commonly used in women than in men (16% vs 13.3%).

Sick sinus syndromeIn SSS patients with permanent atrial tachyarrhythmia, VVI/R was the preferred pacing mode (86.2%). We assume that the use of this type of system is due to doubts about whether to classify AF as permanent or persistent (and, thus, whether AF is amenable to sinus rhythm reversion). For pacing patients in sinus rhythm, there was a slight increase in the use of modes capable of maintaining AV synchrony (77.9%). DDD/R pacing was used in 75.9% while AAI/R mode was rarely used, as mentioned previously. Single-chamber ventricular pacing was maintained at 22.1%. As in previous years, the choice of pacing mode was influenced by the type of SSS, with a 3-fold higher rate of VVI implantation in EPPIC subgroup E2 (bradycardia-tachycardia syndrome): 39.4% vs the 11% to 13% seen in the other subgroups. Once again, these differences were accentuated with age, with the rate of VVI/R pacing reaching 44.8% in octogenarians with bradycardia-tachycardia syndrome.

There were no significant differences by sex in young patients with DDD/R pacing, which was about 90% in both men and women. However, among octogenarians in the other SSS subgroups, DDD/R pacing was used in 30% of women but in 21% of men.

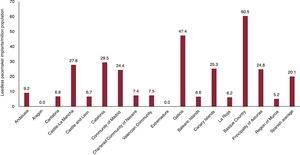

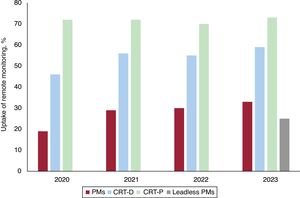

Remote monitoringIn 2023, remote monitoring was included in 28% of conventional pacemakers, 63% of CRT-P devices, and 71% of CRT-D devices, continuing its upward trend. For the first time in the national registry, monitoring data were available for leadless pacemakers, which represented 25% (figure 8). Regional differences were stark. The autonomous communities with the highest percentages of devices equipped with remote monitoring were La Rioja, the Canary Islands, Asturias, and Navarre, which all exceeded 70%. In contrast, less than 20% of devices implanted in Castile-La Mancha had remote monitoring capability. Specifically for conventional pacemakers, La Rioja was once again at the top of the list, with 60% of devices included in a remote monitoring program, while this type of program was practically unused in Cantabria and the Balearic Islands (figure 3 of the supplementary data).

DISCUSSIONIn 2023, 24 343 cardiac pacing device implants were reported to the recording platform of the Heart Rhythm Association of the SEC. This figure represents a highly significant increase vs previous years. In addition, the number of hospitals reporting implants increased by 30 vs 2022. Equally, the number of records included in CardioDispositivos increased by 16 percentage points more than in 2022, a highly positive finding that encourages us to continue raising awareness of the need for centers to report all implants. These data must be reported, not only to support a quantitative national registry, but also for the pharmacovigilance of implanted material. The recording platform of the Heart Rhythm Association of the SEC encourages the direct inclusion of implantation activity in CardioDispositivos or via gateways from compatible platforms that facilitate their integration via automated methods. Of all the devices implanted in Spain reported by Eucomed (45 120 devices), 54% were registered via CardioDispositivos (exceeding the 37.7% recorded in 2022), reflecting of the intense efforts of those responsible in the registry and the collaboration with Spanish hospitals.

By autonomous community, Castile and León, Galicia, Madrid, and Asturias were once again at the top of the list for implants per million population. They are also the most communities with the oldest populations (with the exception of Madrid). Compared with other European countries, Spain is at the bottom of the list with 891 units/million population according to Eucomed9 (2022 data; data from 2023 were not available at the time of article preparation). This figure is well below the average (1001) and particularly behind countries such as Germany (1206), Italy (1207), and Sweden (1063).

Leadless pacemakers were the devices showing the greatest increase vs the previous year (18.1%). Part of this increase might be due to the easing of approvals and administrative processes required in some autonomous communities. Catalonia and Madrid were the communities with the highest numbers of implants, but Andalusia and the Basque Country exhibited the greatest growth vs 2022. A notable development is the release of a new active-fixation device from another distributor. Overall, leadless devices represented 2.2% of all pacemakers, which, given the expansion of current indications,17 is likely an underprescription. The underuse of this therapy may have several explanations, such as the difference in price with conventional pacemakers, the inability to perform CSP, and the lower experience of centers with these devices.

The subclavian approach remains the most popular venous access route (> 50% of procedures), despite evidence showing that this route increases the incidence of pneumothorax and lead fracture during follow-up.18 Indeed, the recommended access route is axillary or cephalic according to the consensus document of the European Heart Rhythm Association endorsed by the Heart Rhythm Society, Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society, and Latin-American Heart Rhythm Society.19 The apex is still the most commonly used lead position for pacing, although CSP is showing rapid growth (almost 20%). This growth is probably due to awareness of the clinical and even prognostic benefits of CSP, as well as the development of new instruments specifically designed to improve outcome reproducibility.20

DDD/R mode is still the most commonly used pacing mode in AVB, even more than in 2022 (62.1%), with limited use of VDD/R mode. Strikingly, modes capable of maintaining AV synchrony increased in elderly patients (> 80 years), undoubtedly due to quality of life improvements and greater use of leadless VDD pacemakers. Differences by sex persisted, with increases directly related to age.

In SSS, the implantation of pacemakers favoring AV synchrony slightly increased from 2022, reaching 75.9%, but fell to 68.1% in octogenarians. This result is likely due to decreased quality of life with age and the fact that most of these patients have permanent AF.

For the first time, AF/atrial flutter with slow or blocked ventricular response was the second most common device indication. There was no increase in AV node ablation in 2023 vs previous years (Spanish Catheter Ablation Registry data, pending publication); in fact, there was a decrease. Thus, the most probable cause is an increased prevalence of this arrhythmia due to population aging.

There was a significant stagnation in the growth of resynchronization devices vs previous years, with a slight increase (1.4%) almost entirely due to CRT-P devices (2.1%). The most plausible explanation could be another sharp increase in CSP due to the consistent clinical evidence published in 2022. Several randomized trials21–23 have compared CSP and biventricular pacing in patients indicated for cardiac resynchronization and confirmed the superiority of CSP in terms of functional class and left ventricular ejection fraction.24 The CardioDispositivos platform allows reporting of lead location in the conduction system. Nonetheless, a physiological pacing registry is also available.25 According to Eucomed data, our implantation rate per million population is half that of the European average for both CRT-P devices (69/million) and CRT-D devices (123/million). These differences are very similar to those of previous years and, even though the use of CSP for cardiac resynchronization is likely higher in Spain than in the rest of Europe,26 there may still be a low indication for this therapy in patients with heart failure symptoms and left bundle branch block.

The use of remote monitoring programs is slowly but continually growing. The programs have a demonstrated prognostic impact in patients implanted with pacemakers and defibrillators and also reduce emergency department visits and face-to-face consultations.27 However, despite current recommendations,28 the widespread use of this technology in all devices remains distant. Notably, La Rioja is the autonomous community with the most devices included in such programs.

LimitationsThe main limitation is the heterogeneity of the data reported by hospitals due to the different sources of information. Although the number of centers participating in the registry increased, many implanting centers do not report their data. Because data submission is still incomplete, a certain percentage of data was missing for each variable. This figure was very high in some cases.

CONCLUSIONSIn 2023, the number of units reported to the recording platform of the Heart Rhythm Association increased by 48.1% vs 2022. Of the total number of implanted devices, the greatest growth was seen in CRT-P devices (2.1%), particularly in leadless pacemakers (18.1%). CSP continued its rapid growth and the use of remote monitoring also increased, albeit at a slower rate.

FUNDINGThe registry is partly funded through an agreement between the Spanish Agency of Medicines and Medical Devices and the Casa del Corazón Foundation. This agreement channels a registered grant established in the 2023 Spanish budget for the management and maintenance of the national pacemaker and implantable defibrillator registries.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONSR. Cózar-León and F.J. García-Fernández performed the data collection, data analysis, and article drafting. M. Molina-Lerma performed the data collection, data analysis, article drafting, and final revision. D. Calvo performed the registry coordination work, data integration, critical revision, and final approval.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTR. Cózar-León receives consultancy fees from Medtronic, Abbott, and Boston Scientific; M. Molina-Lerma receives consultancy fees from Abbott, Medtronic, Boston Scientific, and Microport. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

The authors wish to thank the technical team of the Heart Rhythm Association registries of the SEC, the staff of the Spanish Society of Cardiology (Gonzalo Justes, Miguel Salas, Israel García, and Jesús de la Torre) for their outstanding work in the management and data integration that make this work possible, and the manufacturing and marketing industry for their collaboration.

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rec.2024.07.012