This article presents data on implantable cardioverter-defibrillator implants in Spain in 2022.

MethodsThe data were collected from implantation centers, which voluntarily completed a data collection sheet during the implantation process, either manually or through a web page.

ResultsIn 2022, 170 hospitals participated in the registry. A total of 7693 forms were received compared with the 7970 reported by Eucomed (European Confederation of Medical Suppliers Associations), representing 96.5% of the devices. The total rate of registered implants was 162/million inhabitants (168 according to Eucomed), showing a slight increase compared with previous years. Disparities persisted among autonomous communities and Spain continued to have the lowest implantation rate among countries participating in Eucomed.

ConclusionsThe data from the registry for 2022 reflect the complete recovery of activity after the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. Despite a slight improvement, there was no significant change in our position in Europe or in the substantial differences among autonomous communities.

Keywords

Implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs) are essential for improving the prognosis of patients who have survived or are at risk of cardiac arrest due to a ventricular arrhythmia. Numerous clinical trials have demonstrated the role of these devices in the prevention of sudden cardiac death (SCD) in patients with heart failure and left ventricular systolic dysfunction or severe ventricular arrhythmias.1,2 When combined with cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT), ICDs improve functional class and left ventricular contractile function, decrease left ventricular diameters, and reduce hospitalization and mortality among patients with heart failure, severe systolic dysfunction, or intraventricular conduction disorders.3

The indications for ICD therapy for patients with or at risk of ventricular arrhythmias are listed in several clinical practice guidelines and include primary and secondary prevention of SCD.1–3 SCD is one of the leading causes of death in Western countries, accounting annually for 400 000 deaths in Europe and around 30 000 in Spain. Approximately 40% of deaths occur in people younger than 65 years.4

The Heart Rhythm Association of the Spanish Society of Cardiology (SEC) has produced an annual report on the Spanish ICD Registry since 2005.5–8 In this article, we present the data on ICD implantations performed in Spain submitted to the registry in 2022.

MethodsThe Spanish ICD Registry contains information that is voluntarily submitted by participating hospitals during de novo ICD implantations and replacements. This information is then entered into the registry database by a team comprising a technician, a computer scientist from the SEC, and a member of the Heart Rhythm Association. The data presented in the current report were cleaned by the technician and the first author. All authors analyzed the data and are responsible for this publication. Since 2019, participating hospitals have been able to submit data via an online platform designed by the SEC. In 2022, this platform was used to submit information on 1816 implantations (23.6% of all procedures reported).

Implant rates per million population for Spain and for each autonomous community and province were calculated using population data for the first quarter of 2023 obtained from the Spanish National Institute of Statistics.9 As in previous years, the registry data were compared with statistics collected by the European Confederation of Medical Suppliers Associations, Ecomed.10

The percentages for all variables analyzed were calculated by taking into account the information available for each variable and the total number of implants. When concurrent arrhythmias were reported, the most serious type was selected.

Statistical analysisData are expressed as mean±SD or median [interquartile range] depending on the normality of distribution. Continuous quantitative variables were analyzed using analysis of variance or the Kruskal-Wallis test, while qualitative variables were analyzed using the chi-square test. Linear regression models were used to analyze the number of implants and implanting centers per million population, the total number of implants, and the number of primary prevention implants per hospital.

ResultsSpanish hospitals submitted a total of 7693 implantation forms to the Spanish ICD registry in 2022. Considering that Eucomed reported 7970 ICD implants for the same year, this represents a reporting rate of 96.5%.

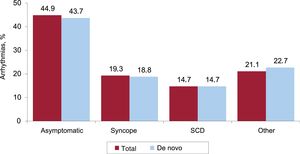

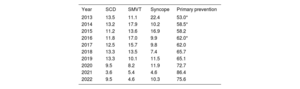

Implanting centersA total of 170 hospitals participated in the Spanish ICD registry in 2022. This figure is down from previous years (198 in 2021, 173 in 2020, 172 in 2019, 173 in 2018) due to a reduction in the number of hospitals with low procedure volumes. The data for the 170 hospitals are shown in table 1. Numbers of implanting centers, implants per million population, and implants per autonomous community according to the data submitted are shown in figure 1. Twenty-five hospitals (23 in 2021) implanted ≥100 ICDs, and 5 of these implanted >200. Sixty-seven hospitals (74 in 2021) implanted 11-99 devices and 78 (101 in 2021) implanted ≤10. In this last group, 13 (28 in 2021) implanted just 1 device.

Implantation activity by autonomous community, province, and hospital

| Autonomous community and province | Hospital | Implants, No. |

|---|---|---|

| Andalusia | ||

| Almería | Hospital Mediterráneo | 7 |

| Hospital Universitario Torrecárdenas | 69 | |

| Hospital Virgen del Mar | 3 | |

| Cádiz | Hospital Jerez Puerta del Sur | 2 |

| Hospital Quirónsalud Campo de Gibraltar | 2 | |

| Hospital San Carlos de San Fernando | 5 | |

| Hospital Universitario Jerez de la Frontera | 60 | |

| Hospital Universitario Puerta del Mar | 77 | |

| Hospital Universitario Puerto Real | 31 | |

| Córdoba | Hospital Cruz Roja de Córdoba | 2 |

| Hospital QuirónSalud Córdoba | 2 | |

| Hospital Universitario Reina Sofía | 88 | |

| Granada | Hospital de la Inmaculada Concepción | 5 |

| Hospital Universitario Clínico San Cecilio | 54 | |

| Hospital Universitario Virgen de las Nieves | 68 | |

| Hospital Vithas Granada | 1 | |

| Huelva | Hospital Costa de la Luz | 2 |

| Hospital Universitario Juan Ramón Jiménez | 55 | |

| Jaén | Hospital Universitario de Jaén | 69 |

| Málaga | Hospital El Ángel | 4 |

| Hospital QuirónSalud Málaga | 2 | |

| Hospital QuirónSalud Marbella | 5 | |

| Hospital Universitario Virgen de la Victoria | 294 | |

| Hospital Vithas Parque San Antonio | 8 | |

| Hospital Vithas Xanit Internacional | 8 | |

| Seville | Clínica Santa Isabel | 6 |

| Hospital Médico Vithas Sevilla | 1 | |

| Hospital QuirónSalud Sagrado Corazón | 6 | |

| Hospital Universitario Virgen de Valme | 39 | |

| Hospital Universitario Virgen del Rocío | 109 | |

| Hospital Universitario Virgen Macarena | 97 | |

| Aragon | ||

| Zaragoza | Clínica Montpellier, Grupo HLA. S.A.U. | 3 |

| Hospital Clínico Universitario Lozano Blesa | 76 | |

| Hospital QuirónSalud Zaragoza | 3 | |

| Hospital Royo Villanova | 2 | |

| Hospital Universitario Miguel Servet | 199 | |

| Hospital Viamed Montecanal | 1 | |

| Principality of Asturias | ||

| Hospital Centro Médico de Asturias | 2 | |

| Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias | 217 | |

| Hospital Universitario de Cabueñes | 23 | |

| Balearic Islands | ||

| Clínica Rotger | 4 | |

| Grupo Juaneda | 4 | |

| Hospital QuirónSalud Palmaplanas | 7 | |

| Hospital Son Llátzer | 26 | |

| Hospital Universitari Son Espases | 117 | |

| Policlínica Nuestra Sra. del Rosario | 2 | |

| Canary Islands | ||

| Complejo Hospitalario Universitario Insular Materno Infantil | 44 | |

| Hospital Universitario de Gran Canaria Dr. Negrín | 100 | |

| Vithas Hospital Santa Catalina | 1 | |

| Hospital San Juan de Dios de Tenerife | 1 | |

| Hospital Universitario Nuestra Señora de La Candelaria | 82 | |

| Hospital Universitario de Canarias | 57 | |

| Cantabria | ||

| Clínica Mompía | 4 | |

| Hospital Universitario Marqués de Valdecilla | 189 | |

| Castile and León | ||

| Ávila | Hospital Nuestra Señora de Sonsoles (Complejo Asistencial de Ávila) | 7 |

| Burgos | Hospital Universitario de Burgos (Complejo Asistencial Universitario de Burgos) | 86 |

| León | Hospital de León (Complejo Asistencial Universitario de León) | 70 |

| Hospital HM San Francisco | 1 | |

| Salamanca | Hospital Clínico Universitario de Salamanca (Complejo Asistencial Universitario de Salamanca) | 67 |

| Valladolid | Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valladolid | 104 |

| Hospital Recoletas Campo Grande | 4 | |

| Hospital Universitario Río Hortega | 19 | |

| Castile-La Mancha | ||

| Albacete | Hospital General Universitario de Albacete | 84 |

| Ciudad Real | Hospital General de Ciudad Real | 58 |

| Cuenca | Hospital Virgen de La Luz | 17 |

| Guadalajara | Hospital Universitario de Guadalajara | 30 |

| Toledo | Hospital Universitario de Toledo (HUT) | 160 |

| Hospital Universitario Nuestra Señora del Prado | 36 | |

| Catalonia | ||

| Barcelona | Centro Médico Teknon, Grupo QuirónSalud | 35 |

| Centre Mèdic Delfos | 2 | |

| Clínica Sagrada Família | 5 | |

| Hospital Clínic de Barcelona | 225 | |

| Hospital De Barcelona | 2 | |

| Hospital Del Mar | 37 | |

| Hospital El Pilar | 1 | |

| Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau | 143 | |

| Hospital QuirónSalud Barcelona | 7 | |

| Hospital Universitari de Bellvitge | 214 | |

| Hospital Universitari Germans Trias i Pujol | 78 | |

| Hospital Universitari General de Cataluña | 9 | |

| Hospital Universitari Parc Taulí | 33 | |

| Hospital Universitari Vall d’Hebron | 153 | |

| Parc Sanitari Sant Joan de Déu | 12 | |

| Girona | Clínica Girona | 6 |

| Hospital Universitario de Girona Dr. Josep Trueta | 98 | |

| Lleida | Hospital Universitari Arnau De Vilanova de Lleida | 63 |

| Hospital Vithas Lleida | 2 | |

| Tarragona | Hospital Universitari Joan XXIII de Tarragona | 42 |

| Hospital Universitari Sant Joan de Reus | 7 | |

| Valencian Community | ||

| Alicante | Clínica Vistahermosa Grupo HLA | 3 |

| Hospital Clínica Benidorm | 1 | |

| Hospital General Universitario Dr. Balmis | 199 | |

| Hospital QuirónSalud Torrevieja | 2 | |

| Hospital Universitario de San Juan de Alicante | 44 | |

| Hospital Universitario del Vinalopó | 1 | |

| Vithas Hospital Perpetuo Internacional | 1 | |

| Castellón | Hospital General Universitario de Castellón | 70 |

| Hospital Rey Don Jaime | 4 | |

| Valencia | Hospital Cátolico Casa de Salud | 3 |

| Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valencia | 94 | |

| Hospital de Manises | 44 | |

| Hospital General Universitario de Valencia | 99 | |

| Hospital QuirónSalud Valencia | 10 | |

| Hospital Universitario de la Ribera | 60 | |

| Hospital Universitario Dr. Peset Aleixandre | 35 | |

| Hospital Universitario y Politécnico La Fe | 242 | |

| Hospital 9 de Octubre | 5 | |

| Extremadura | ||

| Badajoz | Hospital de Mérida | 3 |

| Hospital Universitario de Badajoz | 171 | |

| Cáceres | Clínica Quirúrgica Cacereña San Francisco | 5 |

| Hospital San Pedro de Alcántara | 36 | |

| Hospital Universitario de Cáceres | 16 | |

| Galicia | ||

| A Coruña | Complexo Hospitalario Universitario de A Coruña | 152 |

| Complexo Hospitalario Universitario de Santiago | 125 | |

| Hospital HM Modelo-Belén | 7 | |

| Hospital Quirónsalud A Coruña | 7 | |

| Hospital San Rafael | 2 | |

| Lugo | Hospital Universitario Lucus Augusti | 23 |

| Orense | Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Ourense | 43 |

| Pontevedra | Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Pontevedra | 14 |

| Grupo QuirónSalud Miguel Domínguez | 3 | |

| Hospital Álvaro Cunqueiro | 116 | |

| Hospital Povisa | 17 | |

| Vithas Hospital Nosa Señora de Fátima | 2 | |

| Community of Madrid | ||

| Clínica La Luz, S.L. | 21 | |

| Clínica Universidad de Navarra | 3 | |

| Clínica Viamed Santa Elena, S.L. | 2 | |

| Hospital Central de La Defensa Gómez Ulla | 10 | |

| Hospital del Henares | 7 | |

| Hospital General de Villalba | 8 | |

| Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón | 131 | |

| Hospital QuirónSalud Sur | 6 | |

| Hospital Ruber Juan Bravo | 6 | |

| Hospital San Francisco de Asís | 1 | |

| Hospital San Rafael | 5 | |

| Hospital Universitario Clínico San Carlos | 173 | |

| Hospital Universitario de Fuenlabrada | 20 | |

| Hospital Universitario Fundación Alcorcón | 29 | |

| Hospital Universitario Fundación Jiménez Díaz | 79 | |

| Hospital Universitario de Getafe | 21 | |

| Hospital Universitario de Torrejón | 12 | |

| Hospital Universitario HM Montepríncipe | 9 | |

| Hospital Universitario HM Puerta del Sur | 1 | |

| Hospital Universitario Infanta Elena | 7 | |

| Hospital Universitario Infanta Leonor | 24 | |

| Hospital Universitario La Paz | 155 | |

| Hospital Universitario Puerta de Hierro-Majadahonda | 124 | |

| Hospital Universitario QuirónSalud Madrid | 2 | |

| Hospital Universitario Ramón y Cajal | 86 | |

| Hospital Universitario Rey Juan Carlos | 25 | |

| Hospital Universitario Severo Ochoa | 7 | |

| Hospital Universitario Vithas Madrid Arturo Soria | 6 | |

| Hospital Universitario Virgen de la Paloma, S.L. | 1 | |

| Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre | 105 | |

| Region of Murcia | ||

| Hospital Clínico Universitario Virgen de La Arrixaca | 56 | |

| Hospital General Universitario J.M. Morales Meseguer | 27 | |

| Hospital General Universitario Reina Sofía | 17 | |

| Hospital General Universitario Santa Lucía | 37 | |

| Hospital La Vega Grupo HLA | 4 | |

| Hospital Rafael Méndez | 24 | |

| Chartered Community of Navarre | ||

| Clínica Arcángel San Miguel-Pamplona | 5 | |

| Clínica Universidad de Navarra | 17 | |

| Hospital Universitario de Navarra | 76 | |

| Basque Country | ||

| Álava | Hospital Universitario Araba | 64 |

| Guipúzcoa | Hospital Universitario Donostia | 133 |

| Policlínica Guipuzcoa | 5 | |

| Vizcaya | Clínica IMQ Zorrotzaurre | 2 |

| Hospital de Galdakao-Usansolo | 32 | |

| Hospital Universitario de Basurto | 58 | |

| La Rioja | ||

| Hospital San Pedro | 62 | |

The implanting center was specified in 99.9% of cases (table 1). Most procedures (7235, 94%) were performed in a public hospital.

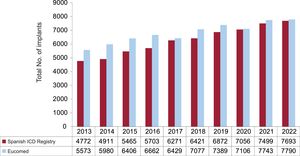

Total number of implantsThe total number of ICD implants reported to the registry over the past 10 years and the corresponding Eucomed estimates are shown in figure 2. In 2002, information was submitted for 7693 procedures, including de novo implants and replacements. This is a historic high for the registry and represents an increase of 2.6% compared with 2021 (7499 implants). The 2022 Eucomed estimate for 2022 (7970 implants) is also the highest to be reported since the creation of the Spanish ICD registry and represents a 2.9% increase with respect to 2021 (7743 implants).

Changes in the number of implants per million population reported by the ICD registry and Eucomed are shown in figure 3. The Eucomed estimate for 2022-168 implants per million population-is higher than in recent years (163 in 2021, 150 in 2020, and 157 in 2019), but still well below the mean for Europe, which was 296 units per million population in 2021, when normal hospital activity had resumed in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic.10

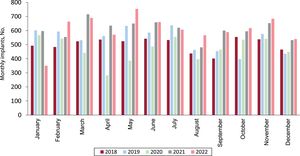

Monthly implantation figures for 2018 to 2022 are shown in figure 4, which reflects variations throughout the year, with a notable drop in April and May 2020 (COVID-19 pandemic) followed by a return to normal levels. ICD implantation activity throughout 2022 can be considered normal. The findings are similar to those observed in 2021 and were minimally impacted by the COVID-19 waves that occurred during the year.

Age and sexThe mean age of patients included in the Spanish ICD registry in 2022 was 62.4±13.9 years (range, 2-92 years). Similar to previous years, de novo ICD recipients were slightly younger (61.6±13.5 years). Also in line with previous findings, the patients were overwhelmingly male (82.4% of patients overall and 83.7% of de novo implant recipients).

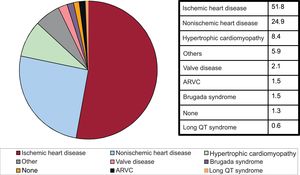

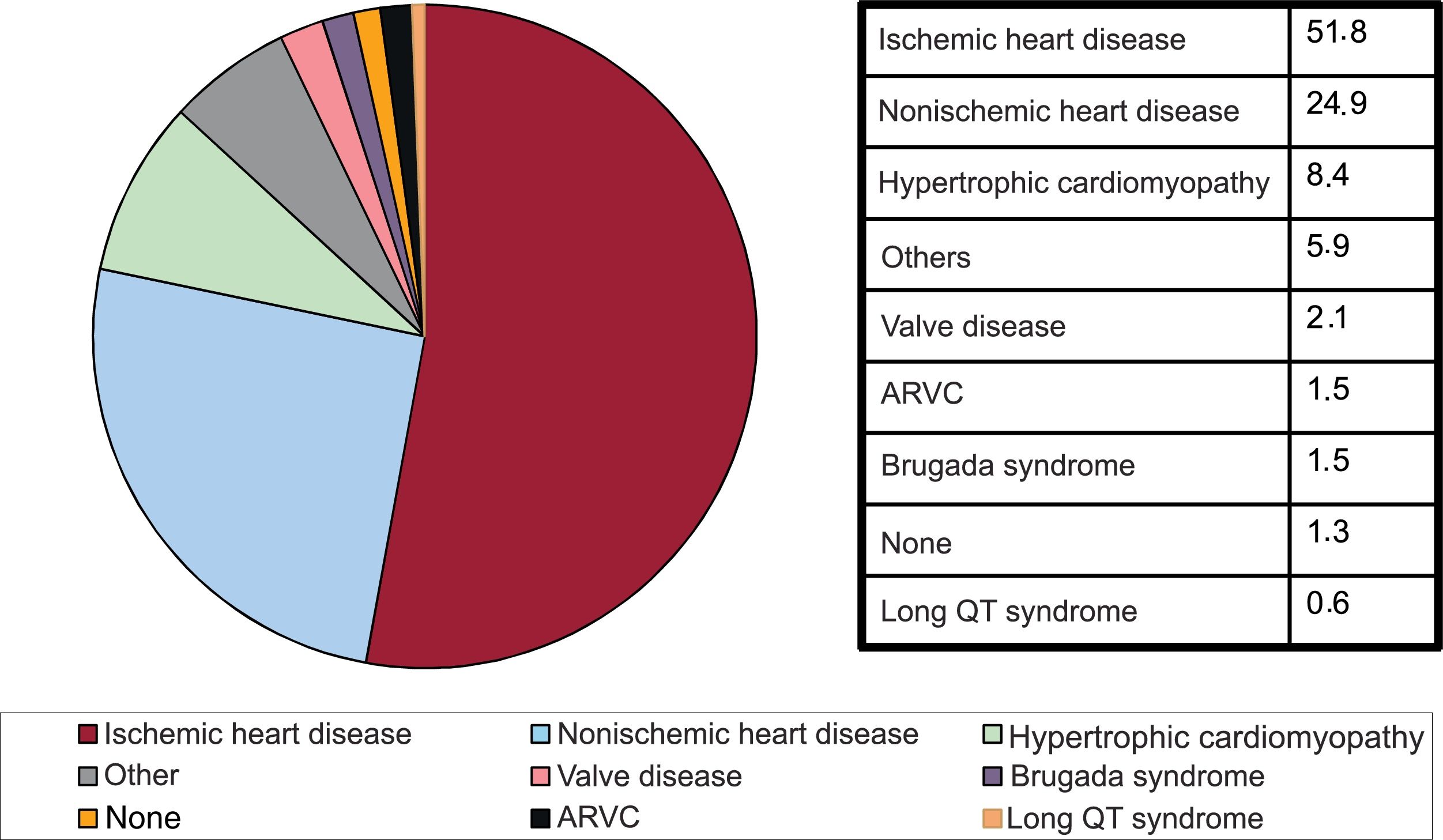

Underlying heart disease, left ventricular ejection fraction, functional class, and baseline rhythmIschemic heart disease was the most common heart disease in de novo ICD recipients (51.8%), followed by dilated cardiomyopathy (24.9%), hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (8.4%), primary electrical diseases–Brugada syndrome and long QT syndrome– (2.1%), valve disease (2.1%), and arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (1.5%) (figure 5).

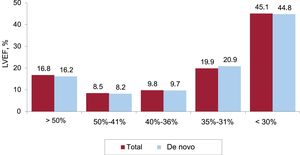

Left ventricular systolic function was reported in 41% of cases. Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was >50% in 16.7% of patients, 50% to 41% in 8.5%, 40% to 36% in 9.8%, 35% to 31% in 19.9%, and ≤30% in 45.1% (figure 6). The values were similar among patients receiving their first implant and those undergoing replacement.

New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class was specified in 22.6% of registry forms. Most patients were in class II (64.9%); 21.9% were in class II, 11.9% in class I, and 1.2% in class IV. Again, the distribution was similar on analyzing de novo recipients and those undergoing replacement.

Baseline rhythm was reported for 41.3% of cases. At the time of implantation, 78.4% of patients were in sinus rhythm, 17.3% had atrial fibrillation, and 3.5% had a pacemaker rhythm. The remaining patients had atrial flutter or other arrhythmias.

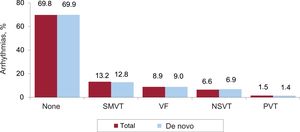

Clinical arrhythmias leading to ICD implantation, clinical presentation, and arrhythmias induced in the electrophysiology laboratoryClinical arrhythmias leading to ICD implantation were specified in 44.3% of forms and are shown in figure 7. Most de novo implant recipients (69.9%) did not have documented clinical arrhythmias, 12.8% had sustained monomorphic ventricular tachycardia, 9% had ventricular fibrillation, and 6.9% had nonsustained ventricular tachycardia.

Almost 44% of patients were asymptomatic. Less common clinical presentations were syncope, aborted SCD), and other symptoms (figure 8).

The electrophysiology study section of the form was completed in 40.6% of cases. This study was performed before ICD placement in 196 patients (6.2% of patients for whom information was provided). It was performed more often in those with ischemic heart disease, dilated cardiomyopathy, and Brugada syndrome (41.8% of patients for whom these diagnoses were specified). The most common arrhythmia induced electrophysiologically was sustained monomorphic ventricular tachycardia (67.3%), followed by ventricular fibrillation (24.3%), nonsustained ventricular tachycardia (6.5%) and other arrhythmias (1.9%). No arrhythmias were induced in 20.2% of cases.

IndicationsThe main indications for ICD implantation between 2018 and 2022 are shown in table 2. This information was submitted for 54.5% of cases in 2022. Ischemic heart disease is the most common indication in Spain, and in 2022, it accounted for 51.8% of all de novo indications. Primary prevention was the most common indication for ICD therapy in patients with ischemic heart disease (64.7%). The second most common indication overall was dilated cardiomyopathy (24.9% of all de novo implant recipients had this diagnosis). In total, 696 patients with dilated cardiomyopathy underwent ICD implantation in 2022, confirming the downward trend observed in 2021 with respect to previous years (619 in 2021, 1214 in 2020, 925 in 2019, and 803 in 2018). Most ICDs implanted in patients with less common heart diseases were for primary prevention.

Number of de novo implants by type of heart disease, clinical arrhythmia, and clinical presentation from 2018 to 2022

| Heart disease | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ischemic heart disease | |||||

| Aborted SCD | 165 (10.6) | 202 (11.2) | 183 (8.7) | 46 (6) | 119 (8.4) |

| SMVT with syncope | 92 (5.9) | 132 (7.3) | 105 (5.2) | 48 (6.3) | 64 (4.5) |

| SMVT without syncope | 231 (14.9) | 232 (12.9) | 204 (9.7) | 71 (9.3) | 124 (8.7) |

| Syncope without arrhythmia | 62 (3.9) | 62 (3.4) | 128 (6.1) | 20 (2.6) | 66 (4.7) |

| Prophylactic indication | 793 (50.8) | 988 (54.9) | 1.173 (56.1) | 445 (56.2) | 916 (64.7) |

| Missing/unclassifiable | 217 (13.9) | 181 (10.7) | 299 (14.3) | 135 (17.6) | 127 (8.9) |

| Subtotal | 1.560 | 1.797 | 2.092 | 765 | 1.416 |

| Dilated cardiomyopathy | |||||

| Aborted SCD | 47 (5.6) | 42 (4.5) | 74 (5.9) | 16 (1.1) | 46 (6.6) |

| SMVT with syncope | 39 (4.8) | 45 (4.9) | 51 (4.1) | 19 (1.2) | 28 (4.0) |

| SMVT without syncope | 53 (6.6) | 121 (13.0) | 88 (7.1) | 19 (2.3) | 11 (1.6) |

| Syncope without arrhythmia | 26 (3.3) | 34 (3.7) | 59 (4.7) | 9 (1.1) | 29 (4.2) |

| Prophylactic indication | 355 (44.2) | 547 (59.1) | 766 (61.7) | 278 (33.2) | 238 (34.2) |

| Missing/unclassifiable | 283 (35.2) | 136 (14.7) | 204 (16.4) | 278 (57.8) | 344 (49.4) |

| Subtotal | 803 | 925 | 1.242 | 619 | 696 |

| Valve disease | |||||

| Aborted SCD | 9 (9.8) | 12 (12.4) | 12 (10.8) | 6 (6.3) | 13 (14.3) |

| SMVT | 24 (26.1) | 28 (28.7) | 21 (18.9) | 7 (7.4) | 8 (8.8) |

| Syncope without arrhythmia | 5 (5.4) | 2 (2.1) | 7 (6.3) | 2 (2.1) | 3 (3.3) |

| Prophylactic indication | 37 (40.2) | 45 (46.4) | 52 (46.8) | 23 (24.2) | 20 (24.2) |

| Missing/unclassifiable | 17 (18.5) | 10 (10.3) | 18 (17.1) | 57 (60.0) | 47 (51.6) |

| Subtotal | 92 | 97 | 110 | 95 | 91 |

| Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy | |||||

| Secondary prevention | 48 (19.2) | 45 (14.2) | 80 (20.4) | 82 (20.5) | 31 (12.7) |

| Prophylactic indication | 198 (79.2) | 207 (65.3) | 288 (73.5) | 325 (79.8) | 200 (82) |

| Missing/unclassifiable | 4 (1.6) | 65 (20.5) | 24 (6.1) | 12 (2.8) | 13 (5.3) |

| Subtotal | 250 | 317 | 392 | 419 | 244 |

| Brugada syndrome | |||||

| Aborted SCD | 14 (18.9) | 10 (12.0) | 10 (9.5) | 9 (8.0) | 3 (7) |

| Prophylactic implantation for syncope | 14 (18.9) | 23 (27.7) | 18 (17.1) | 7 (6.2) | 10 (23.2) |

| Prophylactic implantation without syncope | 14 (18.9) | 40 (48.2) | 56 (53.3) | 22 (19.6) | 9 (20.9) |

| Missing/unclassifiable | 17 (23.0) | 10 (12.0) | 21 (20.0) | 74 (66.0) | 21 (48.8) |

| Subtotal | 74 | 83 | 105 | 112 | 43 |

| ARVC | |||||

| Aborted SCD | 4 (10.3) | 4 (8.2) | 5 (8.9) | 3 (4.1) | 5 (11.9) |

| SMVT | 16 (41.0) | 14 (28.6) | 6 (10.7) | 8 (11.0) | 9 (21.4) |

| Prophylactic implantation | 14 (35.9) | 22 (44.9) | 29 (51.8) | 36 (49.3) | 13 (30.9) |

| Missing/unclassifiable | 5 (12.8) | 9 (18.4) | 16 (28.5) | 26 (35.6) | 15 (35.7) |

| Subtotal | 39 | 49 | 56 | 73 | 42 |

| Congenital heart disease | |||||

| Aborted SCD | 7 (15.2) | 6 (14.6) | 3 (7.0) | 2 (2.4) | 4 (6.5) |

| SMVT | 14 (30.4) | 11 (26.8) | 6 (13.9) | 3 (3.6) | 1 (1.6) |

| Prophylactic implantation | 21 (45.6) | 20 (48.8) | 27 (62.8) | 58 (69.8) | 24 (39.3) |

| Missing/unclassifiable | 4 (8.7) | 4 (9.7) | 7 (16.3) | 20 (24.0) | 32 (52.5) |

| Subtotal | 46 | 41 | 43 | 83 | 61 |

| Long QT syndrome | |||||

| Aborted SCD | 9 (24.3) | 15 (40.5) | 9 (21) | 2 (7.2) | 5 (23.8) |

| Prophylactic implantation | 18 (48.6) | 15 (40.5) | 23 (53.6) | 11 (39.9) | 7 (33.3) |

| Missing/unclassifiable | 10 (27.3) | 7 (18.9) | 11 (25.6) | 15 (53.6) | 9 (42.9) |

| Subtotal | 37 | 37 | 43 | 28 | 21 |

ARVC, arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy; SCD, sudden cardiac death; SMVT, sustained monomorphic ventricular tachycardia.

Values are expressed as No. (%).

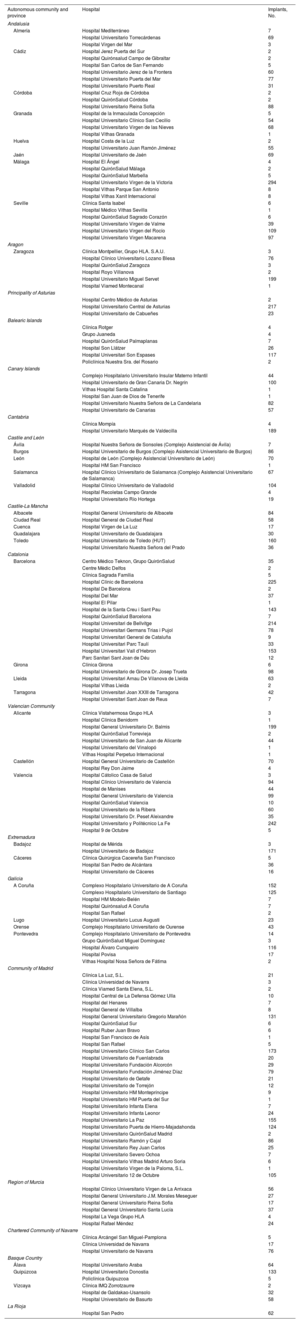

ICD indications were specified in 54.4% of forms. The most common indication reported for de novo implant recipients was primary prevention of SCD (75.6% of cases). Although this rate is lower than in 2021 (86.4%), it supports the upward trend observed in recent years, with values of close of 80% (table 3).

Changes in the main indications for implantable cardioverter-defibrillator implantation in de novo recipients from 2013 to 2022

| Year | SCD | SMVT | Syncope | Primary prevention |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 | 13.5 | 11.1 | 22.4 | 53.0* |

| 2014 | 13.2 | 17.9 | 10.2 | 58.5* |

| 2015 | 11.2 | 13.6 | 16.9 | 58.2 |

| 2016 | 11.8 | 17.0 | 9.9 | 62.0* |

| 2017 | 12.5 | 15.7 | 9.8 | 62.0 |

| 2018 | 13.3 | 13.5 | 7.4 | 65.7 |

| 2019 | 13.3 | 10.1 | 11.5 | 65.1 |

| 2020 | 9.5 | 8.2 | 11.9 | 72.7 |

| 2021 | 3.6 | 5.4 | 4.6 | 86.4 |

| 2022 | 9.5 | 4.6 | 10.3 | 75.6 |

SCD, sudden cardiac death; SMVT, sustained monomorphic ventricular tachycardia.

Data on implantation settings and treating specialists were provided in 51.5% and 49.9% of forms, respectively. Overall, 86.5% of procedures were performed in the electrophysiology laboratory and 12.8% in the operating room. The devices were implanted by an electrophysiologist in 90.2% of cases, a surgeon in 1.9%, an intensive care specialist in 1.7%, a cardiologist in 1.3%, and a combination of specialists in 0.6%.

Generator placement siteGenerator placement site was specified in 51.4% of forms submitted to the registry. Placement was subcutaneous in 97.2% of cases and subpectoral in 2.9%.

Device typeThe ICD devices used by Spanish hospitals in 2022 are shown in table 4. This information was reported for 98.8% of cases and shows an even larger decrease in the use of subcutaneous devices for first-time implants than in previous years. The year 2022 also saw a reduction in CRT-ICD implantations, with the lowest rate observed since 2013. The use of single-chamber ICDs remained stable, at around 51%.

Percent distribution of implanted devices by type

| Total | De novo implants | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | |

| Subcutaneous | 3.6 | 3.8 | 4.4 | 6.2 | 5.7 | 8.6 | 6.1 | 6.4 | 5.3 | 6.0 | 8.3 | 8.1 | 7.3 | 6.5 | ||

| Single-chamber | 48.8 | 48.6 | 45.4 | 45.7 | 46.6 | 45.6 | 45.1 | 46.7 | 46.1 | 48.4 | 49.4 | 50.1 | 47.7 | 50.2 | 52.6 | 51.1 |

| Dual-chamber | 17.4 | 14.5 | 13.7 | 15.0 | 15.0 | 13.8 | 14.1 | 10.6 | 14.5 | 13.0 | 14.1 | 13.4 | 12.6 | 12.4 | 10.5 | 14.4 |

| Resynchronization device | 33.7 | 35.7 | 37.3 | 35.7 | 34.0 | 34.4 | 34.7 | 34.1 | 33.2 | 32.1 | 31.5 | 30.6 | 31.4 | 29.3 | 29.7 | 27.9 |

The main reason for ICD generator replacement was battery depletion (73.2%), followed by upgrading (17.7%), device dysfunction (5%), device infections (1.4%), and other reasons (2.7%).

Lead condition was described in 58.5% of forms, and was defective in 27 cases.

Device programingDevice programing details were provided in 47.4% of forms. The most widely used pacing mode was VVI (50.4%), followed by DDD (21.6%), VVIR (5.9%), DDDR (5.21%), and resynchronization (9.2%). Other modes, which mostly included algorithms or modes to prevent ventricular stimulation, accounted for 9.2% of cases.

Postimplantation induction of ventricular fibrillation was performed at least once in 311 patients (8.6% of those for whom this information was reported). The defibrillation test was mainly performed in patients with a subcutaneous ICD. Just 36 patients with a transvenous ICD underwent ventricular fibrillation induction. The mean number of shocks delivered was 1.06. Accordingly, correct device functioning rather than thresholds was checked in most cases.

ComplicationsInformation on complications was reported in 46.8% of forms. There were 50 complications: 13 coronary sinus dissections, 9 suboptimal left ventricular electrode positions, 4 cases of pneumothorax, 1 tamponade, and 23 unspecified complications. No procedure-related deaths were reported in 2022.

DiscussionA record number of ICD implantations were performed in Spain in 2022, with a total of 162 implants per million population according to registry data and 168 per million population according to Eucomed. Differences, however, remain significant among autonomous communities and overall rates are still well below the 2021 European mean of 296 implants per million population. The data reported to the Spanish ICD Registry in 2022 also confirm that hospital activity has fully returned to pre-COVID-19 levels.11–14

Comparison with recent yearsAlthough more ICD devices than ever were implanted in Spain in 2022, the number of implanting centers decreased with respect to previous years, essentially because of a reduction in the number of hospitals with low volumes of procedures (<100 and in particular<10).

With some exceptions (2011-2012, 2017, and 2020), implantation activity in Spain has increased progressively over the years since the launch of the national ICD registry. There was a 4% reduction in the number of procedures performed in 2020 relative to 2018 and 2019 (the years with the most activity up to 2021), but this was attributable to a general reduction in hospital activity due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Implantation rates returned to normal in 2021, when hospitals resumed normal operation. Although the effects of the pandemic were still somewhat evident in January and February, 2021, they were offset by the increase in procedures over the rest of the year, which ended with a record high. This increase continued into 2022, which set a new record in the number of procedures performed. Nonetheless, and in line with findings from previous years, Spain, with 168 implants per million population, has the lowest implantation rate in all the European Union and is still well behind the European mean of 296 implants per million population reported for 2021.

As evidenced by the above figures, Spain still has a long way to go before it attains a level of activity that would be expected in light of the scientific evidence underlying current clinical practice guidelines.1–3 This situation, however, is not specific to Spain, and its ramifications can be observed in a Swedish study that found that just 10% of patients with an ICD indication for the primary prevention of SCD (according to the European Society of Cardiology [ESC] guidelines) between 2000 and 2016 received a device.15 The same study found that ICD use was associated with a 27% 1-year and a 12% 5-year reduction in mortality. Data from the European EU-CERT-ICD registry have also shown a survival benefit among patients with and without ischemic heart disease who received an ICD for the primary prevention of SCD, with an overall 27% reduction in mortality over a mean follow-up of 2.5 years.16 The Spanish ICD Registry shows that ICD therapy is clearly underused in Spain. The reasons are difficult to pinpoint, but the figures highlight the need to implement measures ensuring that all patients who could benefit from ICD therapy receive a device.

Most (75.6%) of the ICDs implanted in Spain in 2022 were for primary prevention, confirming the upward trend observed in recent years (table 3). Prophylactic ICD therapy has increased by more than 50% in the past 10 years, positioning Spain at a similar level to other European countries, where approximately 80% of implants are for primary prevention.17,18

The percentage of de novo CRT-ICD implants had remained stable, at around 30% in recent years, but in 2022, it was well below this level. There was also an increase in the use of dual chamber ICDs and a stabilization in the use of single-chamber devices. Finally, the data confirmed a downward trend in the use of subcutaneous ICDs among de novo recipients. The rate in 2022 was 6.5%, down from the peaks of 8.3% in 2019 and 8.1% in 2020. Although the favorable results reported for subcutaneous ICDs in 2020 by the PRAETORIAN (Prospective, Randomized Comparison of Subcutaneous and Transvenous Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator Therapy)19 and UNTOUCHED (Understanding Outcomes With the S-ICD in Primary Prevention Patients With Low Ejection Fraction)20 clinical trials indicated that subcutaneous ICD use would gain traction, this has not been the case in Spain. Possible reasons include higher costs per unit and recent safety alerts. Nonetheless, 2 recent subanalyses of data from the PRAETORIAN trial showed that subcutaneous ICDs were effective in the treatment of ventricular arrhythmias21 and associated with fewer device-related complications than transvenous ICDs.22 A new extravascular ICD recently authorized for use in the European Union has a ventricular stimulation feature that provides pause-prevention and antitachycardia pacing.23 The impact of this novel device and emerging evidence on the use of subcutaneous ICDs will become clearer in the years to come.

Ischemic heart disease (51.8%) and dilated cardiomyopathy (24.9%) continue to be the main heart conditions in ICD carriers. Together, they account for more than 75% of all indications for ICD therapy in Spain. The data from 2022, however, show a reduction in the percentage of patients with dilated cardiomyopathy in the registry, which was manifested in a corresponding reduction in the number of prophylactic indications for this disease and probably also explains the reduction in the percentage of CRT-ICD implantations observed. These reductions can be explained by the findings of several recent publications, including the DANISH (Defibrillator Implantation in Patients with Nonischemic Systolic Heart Failure) trial24 and the latest ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of heart failure3 and the management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of SCD.2 Both guidelines, published in 2021 and 2022, respectively, downgraded the recommendation for using ICDs in the primary prevention of SCD in patients with nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy to a level IIa A recommendation. The use of ICDs in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy, however, remains controversial. The 2021 heart failure guidelines recognize a potential survival benefit in patients younger than 70 years and cite the 30% reduction in mortality (hazard ratio [HR], 0.70; 95% CI, 0.51-0.96; P=.03) reported by the DANISH trial.3 The guidelines also refer to the findings of a meta-analysis (including the DANISH trial) that showed an association between ICD therapy and a reduction in all-cause mortality in patients with nonischemic cardiomyopathy.25 The ESC guidelines for the management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias recommend genetic testing (eg, to detect LMNA mutations, which are associated with a high risk of SCD) and assessment of late gadolinium enhancement on cardiac magnetic resonance imaging to improve SCD risk stratification in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy.2 This latter recommendation is based on the findings of several studies and meta-analyses showing that late gadolinium enhancement is superior to LVEF as a risk marker for SCD. Finally, a cost-effectiveness analysis of ICD therapy for the primary prevention of SCD in Spain showed this treatment to be associated with a reduction in all-cause mortality in both ischemic (HR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.58-0.85) and nonischemic heart disease (HR, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.66-0.96).26 Using probabilistic modeling, the study showed cost-effectiveness ratios of €19171 per quality-adjusted life year (QALY) for patients with ischemic heart disease, €31084/QALY for patients with nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy, and €23230/QALY for patients younger than 68 years.26 These results confirm that ICD therapy in Spain is a cost-effective strategy for the primary prevention of SCD in patients with left ventricular dysfunction of ischemic or nonischemic origin, especially in younger populations (<68 years).

Differences among autonomous communitiesSimilar to previous years, the 2022 registry showed significant differences in implant numbers per million population among autonomous communities. The rates were higher than average in several regions, namely Principality of Asturias (n=331), Cantabria (n=242), Extremadura (n=219), Aragon (n=214), La Rioja (n=193), Galicia (n=190), Castile-La Mancha (n=188), the Valencian Community (n=180), and the Basque Country (n=163). Below-average rates were observed in Community of Madrid (n=161), Balearic Islands (n=160), Catalonia (n=151), Castile-León (n=150), Chartered Community of Navarre (n=147), Andalusia (n=139), the Canary Islands (n=130), and Region of Murcia (n=108). The difference between communities with the highest and lowest rates again exceeded 200 implants per million population (265 in 2021, 180 in 2020, and 139 in 2019). The level of disparities across regions in a supposedly uniform health care system such as that of Spain remains a puzzle and indicates that, despite the available evidence and the work of the SEC, hospitals are not applying the same criteria in this area. The differences cannot be explained by differences in income or population density, or by varying rates of ischemic heart disease and heart failure. They do, however, raise questions on the equity of the Spanish health care system in an area as important as SCD prevention.

Comparison with other countriesOn average, 296 devices (ICDs and CRT-ICDs) per million population were implanted in countries covered by Eucomed in 2021. This is higher than the rate of 285 per million population reported for 2020 (the year most affected by the COVID-19 pandemic) and similar to rates from previous years (303 in 2019, 302 in 2018, 307 in 2017, and 316 in 2016). The countries with the highest activity were the Czech Republic, Italy, and Germany, which respectively performed 470, 440, and 436 implantations per million population. Spain again ranked bottom in 2022, with a total of 168 implants per million population, and continues to trail behind other countries with low activity, such as the United Kingdom and Portugal, which respectively performed 197 and 229 implants per million population in 2021.

LimitationsThe Spanish ICD registry collected data on 96.5% of all implants performed in Spain in 2022 according to Eucomed data. As in previous years, and despite the creation of the online CardioDispositivos platform in 2019 to facilitate reporting,27 the completeness of the information submitted was inconsistent across hospitals and less than ideal. Just 23.6% of hospitals used the online platform in 2022, down from 30% in 2021. In addition, the registry does not collect important ICD programming data that would help analyze morbidity and mortality. Combined analyses of parameters such as detection times, heart rate thresholds, and intervals at which supraventricular rhythm discriminators operate are helpful for reducing appropriate and inappropriate therapies. The registry also does not collect follow-up data, limiting thus the conduct of more relevant clinical studies. Finally, inconsistent reporting and a lack of follow-up data probably contributed to an underestimation of procedure- and device-related complications.

Future prospects of the Spanish ICD RegistryThis is the 19th official report of the Spanish ICD Registry. The continued publication of these annual reports is a credit to all participating members of the SEC Heart Rhythm Association. The online platform, a joint initiative of the SEC and the Agencia Española de Medicamento y Productos Sanitarios (AEMPS), has yet to find traction, and its use by hospitals across the country remains inconsistent. To ensure the success of the registry, hospitals need to recognize the importance of the online platform, which facilitates real-time reporting and can serve as a breeding ground for more complex studies.

CONCLUSIONSThe Spanish ICD Registry collected data on 96.5% of all ICD implantations performed in Spain in 2022, thus covering practically all procedures and current uses of this treatment in Spanish hospitals. Although the number of implants per million population reached a record high in 2022, regional disparities persist. In addition, ICD implantation rates remain low compared with other European countries, highlighting the need to improve our ability to identify patients who stand to benefit from ICD therapy.

FUNDINGThe SEC receives funding for the collection and maintenance of data in the Spanish ICD Registry from the Agencia Española de Medicamentos y Productis Sanitarios (AEMPS), the owner of the data.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONSAll the authors analyzed the data, wrote and revised the manuscript, and are responsible for this publication. The first author, together with a technician and a computer scientist from the SEC, was responsible for entering and cleaning the data.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTI. Fernández Lozano has participated in clinical studies sponsored by Abbott and Biotronik and has received fellowship grants from the SEC and the Foundation for Cardiovascular Research. J. Osca Asensi has participated in clinical studies sponsored by Abbott, Boston, and Biotronik. J. Alzueta Rodríguez has received speakers’ fees from Boston and received fellowship grants from the FIMABIS Foundation.