The Working Group on Cardiac Catheterization and Interventional Cardiology presents its annual report on the activity data for 2016.

MethodsAll Spanish hospitals with catheterization laboratories were invited to voluntarily contribute their activity data. The information was collected online and was analyzed mainly by an independent company.

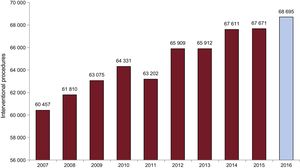

ResultsIn 2016, 106 centers participated in the national registry; 80 of these centers are public. A total of 154 362 diagnostic studies were carried out, of which 135 332 were coronary angiograms. These figures are 14% higher than in previous years. The Spanish average of total diagnostic procedures per million population was 3322 (3.127 in 2015). The number of coronary interventional procedures was 7% higher than in the previous year: 68 695 (67 671 in 2015) and, although multivessel treatment decreased by 3%, unprotected left main trunk treatment increased by 9.4%. A total of 104 628 stents were implanted, of which 88 344 (84.4%) were drug-eluting stents (10% higher than in 2015) and 1610 were bioresorbable scaffolds. A total of 20 588 interventional procedures were performed in the acute myocardial infarction setting (10% increase), of which 83.7% were primary angioplasties. The radial approach was used in 74.2% of the diagnostic procedures, similar to the previous year, and in 82.6% of interventional procedures (7% increase). The number of transcatheter aortic valve implantations continued to increase (28% increase, n = 2026), as did the number of percutaneous mitral valve repair procedures (MitraClip) (45% increase, n = 232) and left atrial appendage closures (48.5% increase, n = 496).

ConclusionsThe number of diagnostic and therapeutic procedures in acute myocardial infarction increased in 2016. The use of the radial approach and drug-eluting stents also increased in therapeutic procedures. The growing trend observed in previous years continued for the use of transcatheter aortic prosthesis, the MitraClip device, and left atrial appendage closure.

Keywords

As in each year since 1990,1–25 the Working Group on Cardiac Catheterization and Interventional Cardiology has collected data on the activity of Spanish cardiac catheterization laboratories. Thus far, data have been voluntarily contributed without audit via an online database to facilitate participation. For the second year running, the website was managed by a specific company, which also made a number of modifications to the database. These changes mainly involved variables related to structural catheterization, due to the continual growth being experienced by this field, and the incorporation of treatment times for ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction (STEMI), such as the door-to-balloon time and the first medical contact-to-balloon time, due to the progressive expansion of the Infarction Code Program in the various autonomous communities. An independent company handled the data analysis, and preliminary data were presented at the annual meeting of the Working Group, which took place on June 8 and 9 in Cadiz, Spain.

An annual national registry is hugely important because it allows yearly evaluation, both overall and by autonomous community, of not only activity, but also improvements in the management of clinical processes and the implementation of health care networks, such as the Infarction Code Program. In addition, the results can be compared with those of the rest of Europe.

As discussed below, 2016 saw increased activity in both coronary interventions and structural heart disease, with a greater number of interventions for STEMI and valvular heart disease. This article represents the 26th report on interventional activity in Spain and collects activity from both public and private centers.

METHODSData were collected on the diagnostic and interventional cardiac activity of most Spanish hospitals. Data were provided voluntarily and without audit. If anomalous data were seen or data that deviated from the trend observed in a hospital in recent years, the center in question was contacted to reassess the data. Data were collected via a standard electronic questionnaire that could be accessed, completed, and consulted through the website of the Working Group on Cardiac Catheterization and Interventional Cardiology of the Spanish Society of Cardiology.26 The Tride company analyzed the data obtained. The Steering Committee of the Working Group compared the data with those obtained in previous years. The results are published in this article, but a preliminary draft was presented as a slideshow at the Working Group's annual meeting.

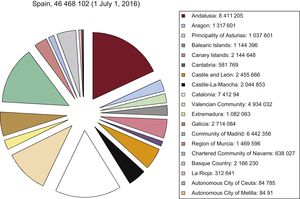

As in previous years, the population-based calculations for both Spain and each autonomous community were based on the population estimates of the Spanish National Institute of Statistics until July 1, 2016.27 The Spanish population was estimated to have decreased to 46 468 102 inhabitants (Figure 1). As in recent years, the number of procedures per million population for the country as a whole was calculated using the total population.

Population of Spain on 1 July 2016. Source: Spanish National Institute of Statistics.27

A total of 106 hospitals performing interventional procedures in adults participated in this registry; most (n=80) were public centers (Appendix). There were 218 catheterization laboratories: 139 (63.7%) were exclusively for cardiac catheterization, 55 (25.2%) had shared activity, and 24 (11%) were hybrid rooms.

The hospitals reported 698 staff physicians performing interventional procedures in 2016 (443 of them accredited) and 80 fellows in training. In addition, there were 640 registered nurses and 83 radiology technicians.

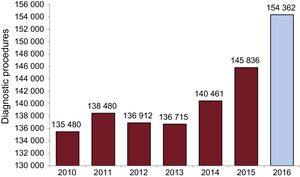

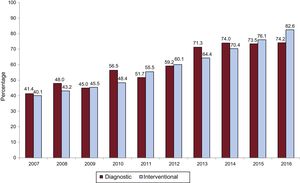

Diagnostic ProceduresIn 2016, 154 362 diagnostic studies were performed; 135 332 (88%) of these procedures were coronary angiograms. These figures represent increases of 5.8% and 5.2% over the previous year, respectively. A total of 11 119 diagnostic studies (7.2%) were performed in patients with valvular heart disease. The changes over time in diagnostic activity are shown in Figure 2. The number of diagnostic procedures performed using the radial approach increased slightly in 2016, from 107 226 (73.5%) in 2015 to 115 504 (74.2%).

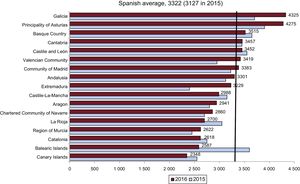

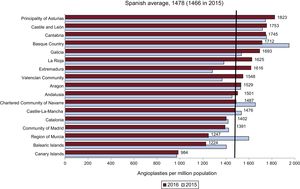

The average number of diagnostic studies was 3332 procedures per million population in Spain, a slight increase from the trend seen in previous years (3127 in 2015). The average number of total coronary angiograms per million population in Spain was 2912 (2746 en 2015). Finally, regarding diagnostic activity per center, 67 hospitals performed more than 1000 diagnostic studies (64 in 2015) and 20 performed more than 2000 (17 in 2015). The average number of diagnostic procedures per hospital was 1456 (1388 in 2015). The numbers of total diagnostic studies per million population by autonomous community are shown in Figure 3. The number of myocardial biopsies slightly increased from that in 2015 (1652) to 1682.

Diagnostic studies per million population. Spanish average and total by autonomous community in 2015 and 2016. Source: Spanish National Institute of Statistics.27

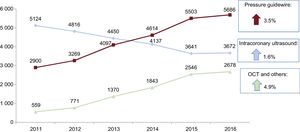

Finally, as in previous years, the trend in the use of intracoronary diagnostic techniques continued, with a predominance of the pressure guidewire as first-line treatment, with an increase of 3.5% in 2016. The use of optical coherence tomography also increased (by 4.9%). In contrast to 2015, the decrease seen in previous years in the use of intracoronary ultrasound seems to have stopped this year and there was even a slight increase (of 1.6%) (Figure 4).

Percutaneous Coronary InterventionsIn 2016, 68 695 percutaneous coronary interventions (PCIs) were performed, more than in 2015 (67 671). The percentage of complex procedures such as PCI for lesions of the left main vessel was also higher than in the previous year (3439; 12.5% higher) and was 70.8% for the unprotected left main trunk. However, treatment of multivessel disease decreased slightly to 16 477 cases, representing 24% of the total (27% in 2015). In contrast, the number of chronic total occlusions treated was 3191 (4.6% of all PCIs), more than in the previous year. A total of 7171 bifurcations were treated (10.4% of all PCIs). The changes over time in PCI are shown in Figure 5. The PCI to coronary angiography ratio was 0.5.

As with diagnostic procedures, the use of radial access in PCIs increased to 82.6% (76.1% in 2015). The changes over time in the use of the radial approach in both diagnostic and therapeutic procedures are shown in Figure 6.

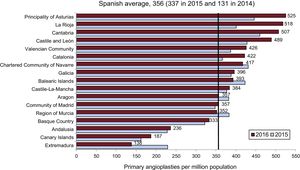

Adjuvant drug therapy other than unfractionated heparin was uncommon and is decreasing (to 7.7%; 12.6% in 2015). Abciximab was used in 6.1% of procedures (7.6% in 2015), whereas eptifibatide and tirofiban were used in less than 1%. Bivalirudin was used in 1.2% of PCIs (2.4% in 2015). The average number of PCIs per million population in Spain was 1478 (1466 in 2015). The numbers of PCIs by autonomous community are shown in Figure 7. In 2016, there was a decrease in the number of communities below the Spanish average: 6 communities in 2016 vs 8 in 2015.

Angioplasties per million population, Spanish average, and total by autonomous community in 2015 and 2016. Source: Spanish National Institute of Statistics.27

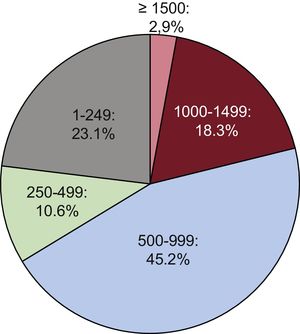

Regarding the distribution per hospital, 22 centers performed more than 1000 PCIs in 2016 (2 less than in 2015), 48 centers between 500 and 1000, and 24 centers less than 250. Data on the immediate clinical outcome variables in PCI were reported for 73% of cases (74% in 2015). In 2016, 98.6% of procedures were successfully performed and without complications; procedures with severe complications (infarction, need for urgent surgery, or death) comprised 1.1%, and intraprocedural death occurred in 0.3%.

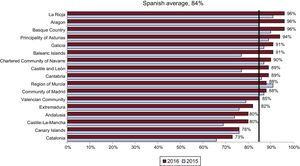

StentsThe number of stents implanted increased in 2016, reaching 104 628, whereas 98 043 were implanted in 2015. The stent to patient ratio was 1.6 (1.4 in 2015, 1.5 in 2014, and 1.6 in 2010). The use of drug-eluting stents increased in absolute terms by 10% in 2016, from 75.6% (74 684) in 2015 to 84.4% (88 344) in 2016. When the use of drug-eluting stents by autonomous community was analyzed, there was an increase in most regions and a large number of communities surpassed the Spanish average (Figure 8).

The prevalence of direct stent implantation was 24.9%, somewhat lower than that of 2015 (38.4%). There were 1610 biodegradable device procedures (1.5% of all stent procedures), far fewer than in the previous year (2685 or 3.9%). There was also a decrease in the number of procedures using bifurcation stents (240; 0.2% of the total), self-expanding stents (80; 0.1%), and polymer-free stents (3368; 3.2%) vs 2015 (294 [0.4%], 164 [0.2%], and 3395 [5.0%]), respectively.

Other Devices and Procedures Used in Percutaneous Coronary InterventionThe reported use of other devices such as rotational atherectomy decreased in 2016 after being stable in previous years, with 1171 cases (1262 in 2015, 1251 in 2014, and 1254 in 2013). The use of special balloons such as cutting balloons slightly increased to 2446 (2285 in 2015). There was also another increase in the use of scoring balloons: 980 in 2014, 1174 in 2015, and 1520 in 2016. In addition, there was increased use of drug-coated balloons: 2575 in 2016 vs 2357 in 2015. The use of thrombectomy catheters decreased again: 8235 devices in 2016 vs 8813 in 2015 and 8981 in 2014. However, the number of distal embolic protection devices stabilized this year, with 128 procedures (132 in 2015 and 305 in 2014).

Percutaneous Coronary Interventions in Acute Myocardial InfarctionThe number of interventions in AMI considerably increased in 2016, by 10.5% (to 20 588 from 18 418 in 2015). Most of these procedures were primary angioplasties, with an increase of 9% vs the previous year to 16 554 (83.7%). Rescue PCIs numbered 988 (954 in 2015). The number of immediate PCIs after pharmacoinvasive reperfusion (< 3hours after administration of thrombolysis and a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa platelet antagonist) doubled in 2016 (558 in 2016 vs 258 in 2015) and delayed or elective PCI after thrombolysis (3-24hours) slightly increased (to 1678 vs 1330 in 2015). These figures are probably due to implementation of the Infarction Code Program in some autonomous communities. Primary PCIs represented 24.1% of all angioplasties and 83.7% of all PCIs in STEMI.

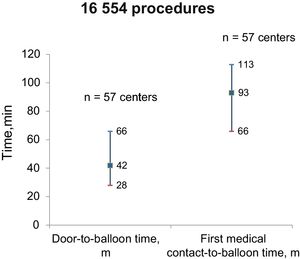

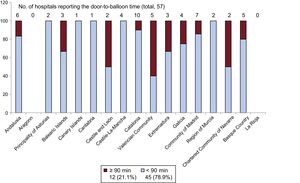

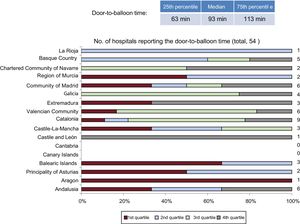

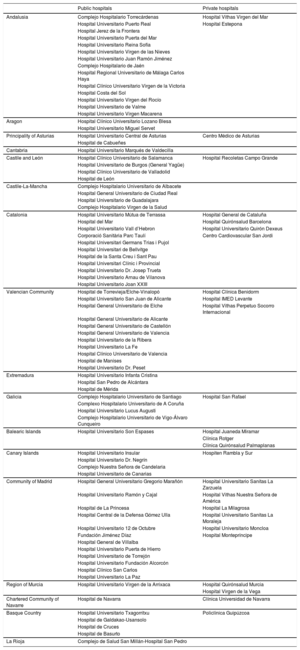

The average number of primary PCIs per million population in Spain was 356 (337 in 2015, 131 in 2014, and 299 in 2013). In general, the number of primary PCIs by autonomous community (Figure 9) showed an overall increase vs 2015. This increase was slightly more marked in the Principality of Asturias, La Rioja, Cantabria, and Castile and León. Five communities were below the national average, 1 more than in 2015. However, there may be a bias because some hospitals may not have included their data; these figures should thus be taken with caution. In 2016, 28 centers performed more than 300 primary PCIs per year (8 centers more than in 2015), whereas 25 centers performed less than 50 (2 less than in 2015) (Figure 10). Regarding primary PCIs, 57 hospitals reported their data to the registry on door-to-balloon time and 54 hospitals provided the first medical contact-to-balloon time, with medians [interquartile range] of 42 [28-66] and 93 [66-113] minutes, respectively (Figure 11). Door-to-balloon time was less than 90minutes in 45 of the hospitals (79%) reporting this information. Figure 12 shows the door-to-balloon times by autonomous community while Figure 13 shows the quartile distributions of the first medical contact-to-balloon time by autonomous community. Each quartile represents the number of hospitals per autonomous community that reported the corresponding datum.

Percentage of centers in each quartile of the door-to-balloon time by autonomous community. The number of centers reporting data from each autonomous community is shown to the right of each bar. Each quartile represents the percentage of centers in each autonomous community indicating the first medical contact-to-balloon time corresponding to this quartile. Quartile 1: values<P25. Quartile 2: values P25-P50. Quartile 3: values P50-P75. Quartile 4: values> P75.

The number of mitral valvuloplasties (233) was largely unchanged this year (235 in 2015 and 256 in 2014). The technique was successful in 226 cases (97%), failed without complications in 7 (3%), and had acute complications in another 7 (3%), which consisted of 7 cases of severe mitral regurgitation; there were no cases of cardiac tamponade, stroke, or death.

In contrast, the number of isolated aortic valvuloplasties, namely those not related to transcatheter aortic valve implantation, stabilized at 231 in 2016 (240 in 2015, 229 in 2014, and 201 in 2013). The procedures were successful in 228 patients (98.7%) and 3 cases with complications (1.29%) were reported, all in patients with severe aortic regurgitation. No deaths were reported.

The number of transcatheter aortic valve implantation procedures markedly increased (27.7%), with 2026 implantations in 2016 (1586 in 2015, 1324 in 2014, and 1041 in 2013). Of the 106 participating hospitals, 66 reported the availability of onsite cardiac surgery. Most valves were implanted in patients with contraindication for surgery or with high surgical risk (63.3% in 2016 vs 73.2% in 2015). However, 17.5% were implanted in patients with intermediate risk; the other patients were not specified. The transfemoral approach was the most widely used, in 1353 procedures (94.5%), followed by the transapical approach, used in 77 procedures (3.8%). Regarding the in-hospital results (reported for 74% of cases), procedural success without any type of major complication was achieved in 74%, less than in 2015 (81.3%). Major complications (AMI, stroke, need for surgery, or vascular complications) were reported in 110 cases (5.4%). Eight patients (0.4%) converted to urgent (< 12hours) nonelective surgery. The reasons for conversion were 3 aorta ruptures, 1 left ventricular perforation, 1 coronary occlusion, and 3 embolizations of the prosthesis to the ventricle. A permanent pacemaker was needed in 224 patients (12%; 10.9% in 2015). In-hospital mortality markedly decreased from 3.2% in 2015 to 0.8% (16 cases) in 2016. The most frequently used prosthesis was the expandable balloon (Edwards; 1016 devices [50.1%] vs 829 [54%] in 2015), closely followed by the self-expanding valve (CoreValve; 835 valves [41.2%] vs 653 valves [41.2%] in 2015); 62 mechanically expandable prostheses (Lotus) were implanted. The remainder were other types, such as the Accurate Neo. Transcatheter mitral valve implantation was performed in 8 patients and transcatheter mitral valve-in-ring implantation in 4 patients. There were 2 cases of transcatheter tricuspid valve implantation (valve-in-valve). Aortic valve-in-valve implantations occurred in 62 patients vs 37 in 2015.

Regarding paravalvular leaks, there was a stabilization in the treatment of aortic leaks—49 in 2016 (50 in 2015 and 127 in 2014)—and an increase in the treatment of mitral leaks—138 in 2016 (112 in 2015 and 168 in 2014). In general, procedural success was achieved in 155 cases (83%) and there were no major complications.

There were 496 atrial appendage closures (334 in 2015); of these, 381 were performed with a disk-and-lobe device (Amplatzer Cardiac Plug/Amulet) and 101 with a 1-piece device (Watchman); 14 other devices (eg, Lambre) were used. Major complications (tamponade, embolization, or death) were observed in 23 patients.

In 2016, 232 transcatheter mitral valve repair procedures (MitraClip) were performed, vs 160 in 2015, with a total of 340 clips (mean number of clips per procedure, 1.47). The most common cause of mitral regurgitation was functional (109 [74.5%]), followed by organic (23 cases [17.7%]). Implantation success was achieved in 225 cases (97%) and there were no deaths.

There were 67 septal ablation procedures (79 in 2015), 42 percutaneous stem cell administration procedures (75 in 2015), 47 endovascular aortic repair procedures (46 in 2015), and 33 renal denervation procedures (50 in 2015).

Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in Adult Congenital Heart DiseaseThe number of atrial septal defect closures decreased from 313 in 2015 and 292 in 2014 to 271 in 2016. There was 1 case of tamponade, 1 case of device embolization, and 2 major complications (death or stroke). Similarly, the number of patent foramen ovale closures decreased to 201 (217 in 2015 and 1176 in 2014) and there were 4 cases of device implantation failure with 1 major complication (death or stroke). There were 37 patent ductus arteriosus closures without complications (25 in 2015) and 21 ventricular septal defect closures (15 in 2015) with 3 cases with complications. Twenty-nine pulmonary valvuloplasty procedures were performed (33 in 2015), with an 82% success rate. A pulmonary valve was implanted in 31 adults (18 in 2015)—21 Melody valves and 10 Edwards valve—, with an 87% success rate (27 patients). Percutaneous stent implantation for aortic coarctation in adults was performed in 44 patients (59 in 2015).

DISCUSSIONThe registry for 2016 showed an increased number of both diagnostic studies and hospitals performing more than 1000 coronary angiograms per year. In total, 25% of diagnostic and therapeutic procedures were performed in patients older than 74 years. Use of the radial access approach continued to increase compared with previous years in both diagnostic and therapeutic procedures and particularly in STEMI and primary angioplasty. This finding is notable because radial access improves mortality by reducing the risk of puncture site bleeding and complications.28

As in previous years, the guidewire was the most widely used intracoronary diagnostic technique, with a slight increase in 2016. Intracoronary ultrasound was the second most used technique, and 2016 was the first year to not show a decrease in its use.

The total number of therapeutic procedures increased vs 2015, mainly due to a higher number of primary angioplasties in AMI, which probably reflects greater adherence of the autonomous communities to the Infarction Code Program. Primary PCI represented 87% of interventional procedures in STEMI. In addition, the proportion of elderly patients undergoing primary angioplasty is growing, with more delayed presentation and a high prevalence of adverse factors. The use of radial access, bivalirudin, drug-eluting stents, and complete revascularization before discharge were identified as protective factors in a recent registry.29

Additionally, there were a greater number of complex procedures, with an increase in unprotected left main trunk treatment. In line with the larger number of cases, there was an increase in the number of stents and progressive growth in the percentage of drug-eluting stents, with almost 10% more in 2016. The use of adjuvant techniques and devices in catheterization procedures, such as rotational atherectomy and thrombus extraction, has stabilized. Direct stent implantation decreased by 14% and there was a notable increase in the use of special balloons (eg, cutting balloons, scoring balloons). Regarding structural interventional cardiology, there were fewer atrial septal defect and patent foramen ovale closures. The number of atrial appendage closures continued to increase, with the same clinical indication: high bleeding risk or contraindication to anticoagulation.30,31 There was another increase in the number of transcatheter aortic valve implantations; a development for 2016 involved expansion of the clinical indication to include patients with intermediate surgical risk, in agreement with the results of studies performed in this type of patient and the reduced relative risk of 2-year death from any cause (13%) in patients treated with transcatheter aortic valve implantation vs those treated with surgery.32 There was another increase in MitraClip treatment of severe mitral regurgitation, with growth of 45% vs 2015. This finding is in line with the good results of various studies, including a Spanish registry33 and a recent meta-analysis34 showing that the MitraClip is effective in patients with heart failure due to functional mitral regurgitation and with high surgical risk, with a low incidence of death and adverse effects, as well as improved functional capacity and cardiac remodeling.

Another development in the current registry is the inclusion of response times for acute infarction. The median first medical contact-to-balloon time was 93 [66-113] minutes. Randomized clinical trials have shown that primary PCI provides a better result than thrombolysis and that early prehospital thrombolysis achieves equally favorable results as primary PCI.35 Based on these data, the current clinical practice guidelines36 recommend primary PCI when the time from first medical contact to balloon use is less than 90minutes. Evaluation of health care quality is important.37 When these time cutoffs are exceeded, patients should be treated with thrombolysis, preferably prehospital, except when contraindicated.

CONCLUSIONSThe Spanish Cardiac Catheterization and Coronary Intervention Registry data for 2016 show another increase in the number of diagnostic and therapeutic procedures, as well as the use of the radial approach. There was also growth in the number of primary angioplasties, drug-eluting stents, and structural heart disease procedures, mainly transcatheter aortic valve implantations, transcatheter mitral valve repair procedures (MitraClip), and appendage closure.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTNone declared.

The Steering Committee of the Working Group on Cardiac Catheterization and Interventional Cardiology would like to thank the directors of cardiac catheterization laboratories throughout Spain, all those responsible for data collection, and all other collaborators for their work.

| Public hospitals | Private hospitals | |

|---|---|---|

| Andalusia | Complejo Hospitalario Torrecárdenas | Hospital Vithas Virgen del Mar |

| Hospital Universitario Puerto Real | Hospital Estepona | |

| Hospital Jerez de la Frontera | ||

| Hospital Universitario Puerta del Mar | ||

| Hospital Universitario Reina Sofía | ||

| Hospital Universitario Virgen de las Nieves | ||

| Hospital Universitario Juan Ramón Jiménez | ||

| Complejo Hospitalario de Jaén | ||

| Hospital Regional Universitario de Málaga Carlos Haya | ||

| Hospital Clínico Universitario Virgen de la Victoria | ||

| Hospital Costa del Sol | ||

| Hospital Universitario Virgen del Rocío | ||

| Hospital Universitario de Valme | ||

| Hospital Universitario Virgen Macarena | ||

| Aragon | Hospital Clínico Universitario Lozano Blesa | |

| Hospital Universitario Miguel Servet | ||

| Principality of Asturias | Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias | Centro Médico de Asturias |

| Hospital de Cabueñes | ||

| Cantabria | Hospital Universitario Marqués de Valdecilla | |

| Castile and León | Hospital Clínico Universitario de Salamanca | Hospital Recoletas Campo Grande |

| Hospital Universitario de Burgos (General Yagüe) | ||

| Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valladolid | ||

| Hospital de León | ||

| Castile-La-Mancha | Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Albacete | |

| Hospital General Universitario de Ciudad Real | ||

| Hospital Universitario de Guadalajara | ||

| Complejo Hospitalario Virgen de la Salud | ||

| Catalonia | Hospital Universitario Mútua de Terrassa | Hospital General de Cataluña |

| Hospital del Mar | Hospital Quirónsalud Barcelona | |

| Hospital Universitario Vall d’Hebron | Hospital Universitario Quirón Dexeus | |

| Corporació Sanitària Parc Taulí | Centro Cardiovascular San Jordi | |

| Hospital Universitari Germans Trias i Pujol | ||

| Hospital Universitari de Bellvitge | ||

| Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau | ||

| Hospital Universitari Clínic i Provincial | ||

| Hospital Universitario Dr. Josep Trueta | ||

| Hospital Universitario Arnau de Vilanova | ||

| Hospital Universitario Joan XXIII | ||

| Valencian Community | Hospital de Torrevieja/Elche-Vinalopó | Hospital Clínica Benidorm |

| Hospital Universitario San Juan de Alicante | Hospital IMED Levante | |

| Hospital General Universitario de Elche | Hospital Vithas Perpetuo Socorro Internacional | |

| Hospital General Universitario de Alicante | ||

| Hospital General Universitario de Castellón | ||

| Hospital General Universitario de Valencia | ||

| Hospital Universitario de la Ribera | ||

| Hospital Universitario La Fe | ||

| Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valencia | ||

| Hospital de Manises | ||

| Hospital Universitario Dr. Peset | ||

| Extremadura | Hospital Universitario Infanta Cristina | |

| Hospital San Pedro de Alcántara | ||

| Hospital de Mérida | ||

| Galicia | Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Santiago | Hospital San Rafael |

| Complexo Hospitalario Universitario de A Coruña | ||

| Hospital Universitario Lucus Augusti | ||

| Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Vigo-Álvaro Cunqueiro | ||

| Balearic Islands | Hospital Universitario Son Espases | Hospital Juaneda Miramar |

| Clínica Rotger | ||

| Clínica Quirónsalud Palmaplanas | ||

| Canary Islands | Hospital Universitario Insular | Hospiten Rambla y Sur |

| Hospital Universitario Dr. Negrín | ||

| Complejo Nuestra Señora de Candelaria | ||

| Hospital Universitario de Canarias | ||

| Community of Madrid | Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón | Hospital Universitario Sanitas La Zarzuela |

| Hospital Universitario Ramón y Cajal | Hospital Vithas Nuestra Señora de América | |

| Hospital de La Princesa | Hospital La Milagrosa | |

| Hospital Central de la Defensa Gómez Ulla | Hospital Universitario Sanitas La Moraleja | |

| Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre | Hospital Universitario Moncloa | |

| Fundación Jiménez Díaz | Hospital Montepríncipe | |

| Hospital General de Villalba | ||

| Hospital Universitario Puerta de Hierro | ||

| Hospital Universitario de Torrejón | ||

| Hospital Universitario Fundación Alcorcón | ||

| Hospital Clínico San Carlos | ||

| Hospital Universitario La Paz | ||

| Region of Murcia | Hospital Universitario Virgen de la Arrixaca | Hospital Quirónsalud Murcia |

| Hospital Virgen de la Vega | ||

| Chartered Community of Navarre | Hospital de Navarra | Clínica Universidad de Navarra |

| Basque Country | Hospital Universitario Txagorritxu | Policlínica Guipúzcoa |

| Hospital de Galdakao-Usansolo | ||

| Hospital de Cruces | ||

| Hospital de Basurto | ||

| La Rioja | Complejo de Salud San Millán-Hospital San Pedro |

![Door-to-balloon and first medical contact-to-balloon times. Data are expressed as median [interquartile range]. Door-to-balloon and first medical contact-to-balloon times. Data are expressed as median [interquartile range].](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/18855857/0000007000000012/v4_201803151517/S188558571730484X/v4_201803151517/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr11.jpeg?xkr=eyJpdiI6Ino1UDNaN0lFUXNYQzk2QitVMSt2MkE9PSIsInZhbHVlIjoiQWw1eFhQVXNoZ1ZBWVMyazZtbmFXODBoRUIrTk9mQk1WTmxBWHZNSDlKQT0iLCJtYWMiOiI5YjQxZDZjYTk0MmIyMWUwNjRiZDllODdkYzBhNDAxMzM1ZTJmMWJjNTMzNjY1ZjkzYjc5MTJhNmZmMmYwNjZkIiwidGFnIjoiIn0=)