Most studies have shown that prognosis of heart failure with preserved systolic function is as poor as that of heart failure with depressed systolic function, although these results may be biased by the fact that these types of heart failure have different characteristics (age, comorbidity, treatment), which can influence prognosis. Our aim was to determine whether short-term morbidity and mortality differed in these 2 subgroups of heart failure patients when they were comparable in terms of age, associated comorbidity, and therapy.

MethodsWe analyzed 2 groups of patients aged >70 years who were candidates to receive beta blockers (preserved systolic function, 245; depressed systolic function, 374), consecutively discharged from 53 participating Spanish hospitals with a diagnosis of heart failure, and compared cardiovascular morbidity and mortality 3 months after discharge.

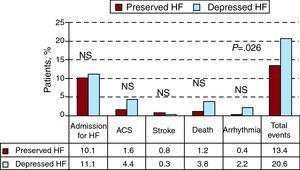

ResultsMean age was similar (77.5±4.8 vs 78.2±5.5 years). Left ventricular ejection fraction was 56.2%±8.1% vs 33%±6.9% (P<.001). The combined event rate (death, hospitalization for heart failure, acute coronary syndrome, or stroke) at 3 months after discharge was lower in patients with heart failure and preserved systolic function (13.4% vs 20.6%; P=.026). Depressed systolic function was an independent predictor of greater incidence of events (odds ratio=1.732; P=.048).

ConclusionsIn patients of similar age and receiving similar treatment, short-term prognosis is better in patients with heart failure and preserved systolic function than in those with depressed systolic function.

Keywords

.

INTRODUCTIONHeart failure (HF) is a clinical syndrome of great relevance due to its high and increasing prevalence1 and high levels of morbidity and mortality.2 These problems are aggravated with age as prevalence increases exponentially with the years1 and prognosis is worse in older patients.3, 4 In recent decades, drugs have been developed that improve prognosis in HF. These include angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI), angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB), antialdosterone drugs, and beta blockers (BB). Their use has facilitated improved prognosis in these patients,5 although producing only a mildly favorable effect in the general population of patients with HF.2 One reason the effect of this treatment in the general population has not been more positive is that–like electrical treatments such as resynchronization or implantable defibrillators– these drugs have only proved efficacious in patients with HF and depressed systolic function.6, 7 No evidence exists about their usefulness to improve prognosis in patients with HF and preserved systolic function, who represent approximately half of the patients with HF.1 In fact, several studies have shown that in recent years mortality in HF with depressed systolic function has fallen, but in HF with preserved systolic function it has not.8, 9 Moreover, the accepted view that low left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was a factor indicating poor prognosis in patients with HF has been changed by numerous studies conducted in Spain and elsewhere10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15 that have shown prognosis was equally poor in patients with preserved LVEF or depressed LVEF.

However, factors other than LVEF itself may influence these results. The characteristics of HF patients with preserved systolic function differ from those of patients with depressed systolic function or depressed LVEF (they are older and have more comorbidities, more of them are women, they have different etiologies and receive different treatments),10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16 and some of these differences, such as greater age, associated comorbidity, or less drug treatment, may unfavorably bias the final result. The objective of our study is to determine whether short-term morbidity and mortality differ in these 2 types of HF, when analyzing groups of patients in terms of age, comorbidity, and treatment received.

METHODSTo achieve our objective, we conducted a subanalysis of the recently published OBELICA study.17 This study, conducted in 2007-2008, included 627 men and women aged ≥70 years and diagnosed with HF according to European Cardiology Society criteria,7 independently of LVEF. Given that the main variable indicating efficacy in this study was the percentage of patients receiving the optimal dosage of BB at 3-month follow-up, the patients included should present no contraindications to BB use. The study was coordinated and overseen by the Spanish Society of Cardiology research agency, and conducted thanks to an unconditional grant from Menarini. Fifty-three hospitals in autonomous regional communities throughout Spain participated in the study (11 in Andalusia, 2 in the Principality of Asturias, 2 in the Balearic Islands, 7 in Valencian Community, 4 in the Canary Islands, 3 in Castile-La Mancha, 4 in Castile and León, 7 in Catalonia, 2 in Extremadura, 3 in Galicia, 5 in the Community of Madrid, and 3 in the Basque Country). Each center included 14 patients consecutively discharged following hospitalization for a principle diagnosis of HF. We defined HF with preserved systolic function as >45% LVEF and HF with depressed systolic function as ≤45% LVEF. At 3 months, we reviewed all patients in cardiology or HF clinics. At each visit we collected demographic, clinical, and treatment data (Table 1, Table 2, Table 3). At the final visit, at 3 months, we also collected data on events since enrollment. Nine patients were lost to follow-up, leaving 618 whose data were included in the final analysis. The principle variable in this subanalysis was the combined outcome of overall mortality and hospitalization for cardiovascular cause (HF, myocardial infarction, unstable angina, stroke, arrhythmias) during the 3-month follow-up. All events were verified by consulting patient clinical case histories for in-hospital cases and by personal or telephone contact with the primary care physician and/or family of patients who died out-of-hospital. The study was approved by the clinical research ethics committee (Hospital General de Alicante) and complied with Spanish legislation on clinical trials. Participants were required to give written informed consent.

Table 1. Characteristics of Patients With Heart Failure and Preserved or Depressed Systolic Function at First Visit.

| PSF (n=246) | DSF (n=372) | P | |

| Age, years | 78.2±5.5 | 77.5±4.8 | .101 |

| Women | 130 (52.8) | 125 (33.6) | <.001 |

| Previous admission for HF | 97 (39.4) | 231 (62.1) | <.001 |

| High blood pressure | 204 (82.9) | 267 (71.7) | .001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 91 (36.9) | 153 (41.1) | .316 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 96 (39) | 190 (51.1) | .004 |

| Myocardial infarction | 65 (26.4) | 193 (51.9) | <.001 |

| COPD | 34 (13.8) | 61 (16.4) | .412 |

| Anemia | 58 (23.6) | 97 (26.1) | .478 |

| Stroke | 26 (10.6) | 38 (10.2) | .857 |

| Smoker | 82 (33.3) | 186 (50) | <.001 |

| Previous coronary revascularization | 42 (17.1) | 109 (29.3) | .002 |

| Functional class | .052 | ||

| I | 24 (9.8) | 31 (8.3) | |

| II | 121 (49.2) | 147 (39.5) | |

| III | 97 (39.4) | 183 (49.2) | |

| IV | 4 (1.6) | 11 (3) | |

| Etiology of HF | <.001 | ||

| Ischemic | 68 (27.7) | 231 (62.1) | |

| Hypertensive | 156 (63.4) | 44 (11.8) | |

| Idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy | 0 | 79 (21.2) | |

| Valvular heart disease | 15 (6.1) | 11 (3) | |

| Other | 7 (2.8) | 7 (1.9) | |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 141±21.2 | 127.3±19.3 | <.001 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 78.4±14 | 74.6±11.6 | <.001 |

| Body mass index | 28.9±4.4 | 27.3±3.8 | <.001 |

| Atrial fibrillation; | 91 (37) | 122 (32.8) | .278 |

| Ejection fraction, % | 56.2±8.1 | 33±6.9 | <.001 |

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DSF, depressed systolic function; HF, heart failure; PSF, preserved systolic function.

Means are compared using Student's t test or the Wilcoxon test for 2 independent samples; proportional homogeneity, using chi-squared.

Results are expressed as n (%) (for qualitative variables) and mean±standard deviation (for continuous variables).

Table 2. Biochemical Parameters for Patients With Heart Failure and Preserved or Depressed Systolic Function at First Visit.

| PSF (n=246) | DSF (n=372) | P | |

| Hemoglobin, g/l | 12.9±1.8 | 12.6±1.8 | .268 |

| BNP, pg/ml | 320.9±398.8 | 458.6±233.8 | .108 |

| Creatinine, mg/dl | 1.2±0.6 | 1.3±0.6 | .127 |

| Sodium, mEq/l | 139.27±3.4 | 139±3.6 | .234 |

| Potassium, mEq/l | 4.4±0.5 | 4.5±0.5 | .078 |

BNP, brain natriuretic peptide; DSF, depressed systolic function; PSF, preserved systolic function.

Means are compared with Student's t test or the Wilcoxon test for 2 independent samples.

Results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation.

Table 3. Drug Treatment of Patients With Heart Failure and Preserved or Depressed Systolic Function at First Visit and at Final Visit 3 Months After Discharge.

| PSF | DSF | P | |

| First visit | |||

| Patients | 246 | 372 | |

| ACEI/ARB | 214 (87) | 337 (90.6) | .074 |

| Digitalis | 49 (20) | 101 (27.2) | .039 |

| Beta blockers | 211 (85.8) | 331 (89) | .169 |

| Statins | 113 (46) | 229 (61.6) | <.001 |

| Anticoagulants | 99 (40.2) | 154 (41.4) | .798 |

| Antiplatelet drugs | 114 (46.3) | 211 (56.7) | .013 |

| Diuretics | 208 (84.5) | 334 (89.8) | .057 |

| Antialdosterone drugs | 47 (19.1) | 169 (45.4) | <.001 |

| Final visit | |||

| Patients | 243 | 358 | |

| ACEI/ARB | 217 (89.3) | 326 (91.1) | .471 |

| Digitalis | 48 (19.7) | 88 (24.6) | .163 |

| Betablockers | 214 (88.1) | 330 (92.2) | .094 |

| Statins | 122 (50.2) | 226 (63.1) | <.001 |

| Anticoagulants | 98 (40.3) | 148 (41.3) | .798 |

| Antiplatelet drugs | 108 (44.45) | 205 (57.3) | .010 |

| Diuretics | 191 (78.6) | 314 (87.7) | .004 |

| Antialdosterone drugs | 45 (18.5) | 162 (45.2) | <.001 |

ACEI, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors; ARB, angiotensin receptor blockers; DSF, depressed systolic function; PSF, preserved systolic function.

Proportional homogeneity is compared with chi-squared.

Results are expressed as n (%).

In 2 groups of patients with HF and preserved or depressed systolic function, we compared baseline characteristics and events at 3-month follow-up using chi-squared for qualitative variables and Student's t test or the Wilcoxon test for continuous variables. A value of P<.05 was considered statistically significant. We also performed stepwise logistic regression multivariate analysis to determine those factors independently associated with a greater rate of events at 3 months. This model included all variables showing statistical significance in univariate analysis (Table 4) and other clinically relevant parameters (history of high blood pressure, diabetes mellitus, HF etiology, treatment with ACEI, BB and antialdosterone drugs) that showed no significant differences in the univariate study.

Table 4. Comparison of Patient Characteristics at First Visit Between Groups With and Without Events During the 3-month Follow-up.

| Cardiovascular event | P | ||

| No (n=508) | Yes (n=110) | ||

| Age, years | 77.4±5 | 79.3±5.2 | <.001 |

| Women | 200 (39.3) | 54 (49.1) | .017 |

| Clinical course of HF in months | 29.5±36.7 | 38.8±46.9 | .065 |

| Previous admissions for HF | 251 (49.4) | 77 (70.2) | <.001 |

| High blood pressure | 389 (76.6) | 82 (74.5) | .513 |

| Diabetes | 200 (39.3) | 44 (40) | .965 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 243 (47.8) | 43 (39.1) | .281 |

| Myocardial infarction | 200 (39.3) | 58 (52.7) | .018 |

| COPD | 75 (14.7) | 20 (18.2) | .746 |

| Anemia | 120 (23.6) | 35 (31.8) | .032 |

| Stroke | 50 (9.8) | 14 (12.7) | .202 |

| Smoker | 226 (44.5) | 42 (38.2) | .079 |

| Previous coronary revascularization | 118 (23.2) | 33 (30) | .133 |

| Functional class | <.001 | ||

| I-II | 290 (57.1) | 33 (30) | |

| III-IV | 218 (42.9) | 77 (70) | |

| Etiology of HF | |||

| Ischemic | 244 (48) | 55 (50) | .450 |

| Hypertensive | 172 (33.8) | 28 (25.5) | .139 |

| Other | 92 (18.2) | 27 (24.5) | .782 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 133.8±21.3 | 127.7±19.9 | .006 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 75.9±12.8 | 74.1±12.5 | .199 |

| Heart rate, bpm | 77.3±16.7 | 76.9±16 | .801 |

| Body mass index | 28.1±4.2 | 27.3±3.9 | .087 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 163 (32) | 50 (45.5) | .046 |

| Ejection fraction, % | 47.5±13.6 | 39.3±12.3 | .023 |

| HF with preserved systolic function | 213 (41.9) | 33 (30) | .026 |

| Hemoglobin, g/l | 12.8±1.8 | 12.3±1.9 | .015 |

| BNP, pg/ml | 404.2±326.1 | 426.9±234.8 | .463 |

| Creatinine, mg/dl | 1.2±0.6 | 1.5±0.8 | .007 |

| Sodium, mEq/l | 139.4±3.4 | 138.5±4.4 | .047 |

| Potassium, mEq/l | 4.4±0.5 | 4.5±0.5 | .213 |

| Treatment | |||

| ACEI/ARB | 455 (89.6) | 96 (87.3) | .126 |

| Digitalis | 122 (24) | 28 (25.4) | .894 |

| Beta blockers | 446 (87.8) | 96 (87.2) | .568 |

| Anticoagulants | 196 (38.6) | 57 (51.8) | .036 |

| Antiplatelet drugs | 268 (52.8) | 57 (51.8) | .929 |

| Diuretics | 437 (86) | 105 (95.4) | .011 |

| Antialdosterone drugs | 178 (35) | 38 (34.6) | .759 |

ACEI, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blockers; BNP, brain natriuretic peptide; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; HF, heart failure.

Means are compared with Student's t test or the Wilcoxon test for 2 independent samples; proportional homogeneity is compared with chi-squared. Results are expressed as n (%) (for qualitative variables) and mean ± standard deviation (for continuous variables).

We enrolled 627 patients; 40% (n=250) with preserved systolic function and 60% (n=377) with depressed systolic function. Nine patients were lost during follow-up: 4 with preserved systolic function and 5 with depressed systolic function. Hence our analysis included data on 618 patients (246 in the first group and 372 in the second). Clinical characteristics during hospitalization and the most important aspects of clinical history are in Table 1. In both groups, mean age was similar at ±78 years. The group with HF and preserved systolic function included a higher percentage of women (52.7% vs 33.7%; P<.001). Previous admission for HF was recorded in 62% of patients with depressed systolic function and 39.6% of patients with preserved systolic function (P<.001). Prevalence of high blood pressure was greater in patients with preserved systolic function; prevalence of hyperlipidemia, smoking, myocardial infarction, and coronary revascularization was greater among those with depressed systolic function (Table 1). Prevalence of atrial fibrillation, diabetes mellitus, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, anemia, and stroke was similar in both groups (Table 1). The most frequent etiology in patients with HF and depressed systolic function was ischemic heart disease (62.1%); in patients with HF and preserved systolic function it was high blood pressure (63.4%; P<.001) (Table 1). LVEF was 56.2%±8.1% in the group with preserved systolic function and 33%±6.9% in those with depressed systolic function (P<.001). No relevant clinical differences were found between groups in biochemical parameters (including brain natriuretic peptide, hemoglobin, and serum creatinine) (Table 2).

Drug TreatmentTable 3 shows drug treatments received by patients in both groups at discharge, during the enrollment visit, and at 3-month follow-up, on the final visit. The percentages of patients receiving ACEI or ARB, diuretics, BB, and anticoagulants were high and similar in both groups. Patients with depressed systolic function received proportionately more antiplatelet drugs, statins, antialdosterone drugs, and digitalis (Table 3). These results changed little on the visit at 3 months after discharge (Table 3), although the percentage of patients taking BB increased slightly in both groups (88.1% in those with preserved systolic function and 92.2% in those with depressed systolic function), and the percentage of patients receiving diuretics fell, particularly in the group with preserved systolic function (Table 3). No differences were found in the percentages of patients reaching the optimal or maximum tolerated dose of BB (39.6% in the group with HF and preserved systolic function and 46.8% in the group with HF and depressed systolic function; P=.08). Incidence of secondary effects caused by BB was also similar (7.7% vs 10.9%; P=.19).

Events During Follow-upFigure 1 shows mortality and the cardiovascular event rate during the 3-month follow-up in both groups. Patients with HF and preserved systolic function presented lower incidence of death and/or cardiovascular-cause admission (13.4% vs 20.6%; P=.026). The mortality rate was three times less in this group (1.3% vs 3.9%), although this was not statistically significant, probably due to the low number of deaths. There were no differences in other events (admissions for decompensation of HF, acute coronary syndrome, stroke, and other causes). Days of hospitalization during the 3 months were also similar (8.0±5.9 vs 8.7±8.5; P=.412). A greater percentage of patients with HF and preserved systolic function were in New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class I or II at 3-month follow-up (88% vs 74%; P<.001). Table 4 compares patients who presented events during the 3-month follow-up and those who did not. The proportion of patients with HF and preserved systolic function was greater in the subgroup with no events (41.9% vs 30.2%; P=.026). In multivariate logistic regression analysis, HF with depressed systolic function was an independent predictor of events at 3 months (odds ratio [OR]=1.732; 95% confidence interval, 1.080-3.061; P=.048), as were NYHA functional class III-IV, age, female sex, previous myocardial infarction, and prior admission for HF (Table 5).

Figure 1. Incidence of events at 3-month follow-up in our patients. ACS, acute coronary syndrome; HF, heart failure; NS, not significant.

Table 5. Independent Predictors of Events During 3-month Follow-up. Results of Logistic Regression Analysis.

| Variable | OR (95%CI) | P |

| Functional class III-IV | 3.295 (1.231-4.235) | .024 |

| Previous myocardial infarction | 1.932 (1.183-3.458) | .028 |

| Age | 1.060 (1.008-1.114) | .021 |

| Depressed HF | 1.732 (1.080-3.061) | .048 |

| Previous admissions for HF | 1.786 (1.052-3.032) | .031 |

| Female gender | 1.675 (1.013-2.770) | .044 |

95%CI, 95% confidence interval; HF, heart failure; OR, odds ratio.

In the last 10 or 15 years, the question of whether the prognosis of patients with HF and preserved systolic function was similar to that of patients with HF and depressed systolic function has provoked controversy. Although depressed LVEF has traditionally been considered a factor in poor prognosis in HF,18 most recent studies,10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 19, 20 but not all,9 have indicated that prognosis in HF with preserved systolic function is similar or equally poor as in HF with depressed systolic function. However, these studies also show that demographic, clinical, and treatment characteristics of these 2 groups of patients differ, and that some of them can bias the prognosis in one direction or the other. In effect, patients with HF and preserved systolic function are older, present greater associated comorbidity, and receive proportionately fewer drugs shown to improve prognosis in patients with HF and systolic dysfunction, like ACEI, antialdosterone drugs, and BB. These factors can make the prognosis of patients with preserved systolic function seem worse than it would be if more homogeneous groups of patients were compared. In some of these studies, the prognosis for the 2 HF sub-types does remain similar after adjusting for some of these variables, but the most precise analytical approach is to compare 2 groups in which potentially confounding variables are equally distributed. The OBELICA study design has enabled us to compare 2 wide-ranging groups of patients with HF and preserved or depressed systolic function who are all of a similar age–quite old, in fact. Comorbidity rates are also the same, as, by and large, is treatment received, with a high proportion–close to 90%-95%–taking ACEI/ARB and BB.17 Only use of antialdosterone drugs, statins and antiplatelet drugs was significantly greater in patients with HF and depressed systolic function (Table 3). The results of our analysis–even with such a short 3-month follow-up after admission for decompensation of HF–indicate cardiovascular morbidity and mortality were significantly lower in patients with HF and preserved systolic function (13.4% vs 20.6%; Figure 1). Even overall mortality was 3 times less in the group with preserved LVEF (1.2% vs 3.8%), although this was not statistically significant, probably due to the low number of deaths associated with the short follow-up. At 3 months, functional class was also better in the group with HF and preserved LVEF: 87.6% of patients with HF and preserved systolic function and 74.4% of those with HF and depressed systolic function (P<.001) were in class I or II.

In the previously mentioned studies,10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 19, 20 lower age and less comorbidity in patients with systolic dysfunction could have reduced morbidity and mortality in these patients, improving their prognosis so that it approached that of patients with preserved LVEF. Our study has not wholly eliminated the comorbidity bias as patients with HF and depressed systolic function presented greater prevalence of smoking, myocardial infarction, or coronary revascularization. However, we have substantially reduced it. Moreover, in the stepwise logistic regression multivariate model, HF with depressed systolic function remained an independent predictor of a greater rate of events. Furthermore, the percentage of patients receiving ACEI or ARB and, above all, BB, was very high and similar in our 2 study groups. This contrasts with the findings of most other studies, in which patients with HF and depressed systolic function received proportionately more BB. Although there is no evidence from controlled clinical trials to show the beneficial effect of these drugs on patients with HF and preserved LVEF21, 22 –hence, probably, they are less frequently used in patients with preserved systolic function–some non-randomized studies indicate BB use may be associated with improved prognosis in these patients.23, 24 Beta blockers can benefit patients with HF and preserved systolic function, either through their negative chronotropic effect or their control of high blood pressure and ischemic heart disease (the principle causes of this problem). In the SENIORS study,24 which also included patients with HF and preserved systolic function, BB had a similar effect in patients with depressed and preserved LVEF. In our study, approximately 90% of patients in both groups received ACEI or ARB and BB, as shown in Table 3.

LimitationsOur study has certain limitations–principally the short, 3-month follow-up due to the design of the original study.17 For the same reason, we excluded from analysis in-hospital deaths prior to discharge. However, the rate of events in patients discharged for HF is greater in the first months of follow-up8, 10, 20, 21, 22 and progressively falls later, so these data do not affect the validity of our study. The curves of events in HF studies would normally be expected to separate gradually over the follow-up period, with the initial trend being accentuated. Consequently, the differences we found probably would have been greater in a longer follow-up. Another limitation, which we have already discussed, is BB use. We do not know their real effect in prognosis of HF with preserved LVEF since no controlled studies have been done, but they may well be beneficial.23, 24 In our study, we eliminated bias due to possible differences derived from proportionately different use of these drugs in one or the other group of patients with HF. Finally, we only enrolled patients treated in cardiology services and excluded those admitted in internal medicine, who usually present greater comorbidity. However, the high mean age of our patients–78 years–reduces this bias.

CONCLUSIONSFrom our results, it can be concluded that the prognosis of patients with HF and preserved systolic function appears better than that of patients with HF and depressed systolic function, at least in the short term. When we eliminate potentially confounding factors in patient characteristics that may influence prognosis–eg, age, comorbidity, and treatment received–morbidity and mortality are significantly lower and the trend in overall mortality is 3 times lower at 3-month follow-up. Studies with these characteristics and longer follow-up are needed to confirm these data.

FUNDINGThe present study was conducted thanks to an unconditional grant from Menarini SA.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTNone declared.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all participating researchers for their efforts, without which this study could not possibly have been conducted. Similarly, we wish to express our thanks to the staff of the Sociedad Española de Cardiología research agency (Agencia de Investigación) and Laboratorios Menarini, for their disinterested contribution to the study.

Appendix.Principal Investigators, OBELICA Study:

Álvarez Auñón, Amparo. Anguita Sánchez, Manuel. De los Arcos, Enrique. Arrarte Esteban, Vicente. Bardaji Mayor, Juan Luis. Berrazueta Fernández, José R. Bertomeu Martínez, Vicente. Bierge Valero, David. Bover Freire, Ramón. Cabeza Lainez, Pedro. Castro Fernández, Antonio. Cremer, David. Fernández Lázaro, Luis Antonio. De la Fuente Galván, Luis. Fuertes Alonso, Jorge. García de Andoain, José María. García de la Villa, Bernardo. García González, Juan Pedro. García Quintana, Antonio. Giménez Cervantes, Diego. Gómez Barrado, José Javier. Gómez Belda, Ana B. González Juanatey, Carlos. González Llopis, Francisco. Guevara Zuazo, Justo. Hernández Alfonso, Julio. Hernández Fernández, Isidro. Iglesias Río, Enrique. Lozano Palencia, Teresa. Martín Santana, Antonio. Martínez Dolz, Luis. Matas González. Mayordomo López, Juan. Molina Laborda, Eduardo. Navarro Lostal, Carmen. Núñez Villota, Julio. Ortiz de Murua, José Antonio. Pabón Osuna, Pedro. Pascual Figal, Domingo. Pastor Torres, Luis. Pérez de Juan, Miguel Ángel. Planas, Francesc. Quintas Ovejero, Laura. Del Río Ligorit, Alfonso. Rodríguez García, Miguel Ángel. Rodríguez Padial, Luis. Roig Minguell, Eulalia. Romero Caballero, Dolores. Romero Menor, César. Roure Fernández, Julia. Ruiz-Valdepeñas, Luis. Sánchez Vega, Eugenio. Soto Priore, Adriana.

Received 25 April 2011

Accepted 6 July 2011

Corresponding author: Damasco 2, 2.o 9.a, 14004 Córdoba, Spain. manuelp.anguita.sspa@juntadeandalucia.es