Coronary artery disease is associated with high morbidity and mortality. The objective of the CLARIFY registry is to study the treatment of outpatients with coronary artery disease in the setting of daily clinical practice.

MethodsThe CLARIFY registry is a prospective registry conducted in 41 countries that included outpatients with stable coronary artery disease attending primary care or specialist units between October 2009 and June 2010. The present study describes the baseline characteristics of the Spanish cohort compared with the western European cohorts included in the registry.

ResultsA total of 33 248 patients were included: 14 726 in western Europe and 2257 in Spain (selected by 192 cardiologists). The majority of the participants in Spain were men (81%) with a mean age of 65 years. There was a higher frequency of diabetes (34% vs 25%; P<.0001), coronary artery disease family history (19% vs 31%; P<.0001), myocardial infarction (64% vs 60%; P<.0001), and stroke (5% vs 3%; P=.0007) in the Spanish cohort than in the western European cohorts. The most common treatments in the Spanish sample were lipid-lowering drugs (96%), acetylsalicylic acid (89%), and beta-blockers (74%).

ConclusionsPatients in the Spanish cohort are similar to those in the western European cohorts and seem to be representative of the Spanish population with coronary artery disease. Therefore, they form a suitable basis for the study of prognostic factors at 5-year follow-up.

Keywords

Coronary artery disease (CAD) remains the leading cause of death in Europe.1 However, data released in 2008 show a recent fall in CAD mortality in most European countries, due to advances in prevention strategies and more effective treatments, whereas it has risen in some central and eastern European countries.1 Although these advances have improved CAD outcomes, the number of CAD patients has increased, changing the clinical practice setting and leading to the high economic burden of €192 billion per year in the European Union.1

The high prevalence, morbidity and mortality, and economic burden of CAD have led to changes in the European guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention.2 These changes include new sections on risk factors, such as heart rate (HR). The importance of HR in the outcome of stable CAD patients has been supported by extensive evidence.3

Information on patients seen in daily clinical practice is needed to determine to what extent the recommendations are being applied and to what degree disease outcomes are improving. Patient data from clinical trials are useful for evaluating treatment, but do not represent clinical practice due to the stringent patient selection process and because patient follow-up and treatment is guided by the trial protocol. Patient registries are the ideal source of information on CAD patients. Although several CAD patient registries have recently been developed, they are limited by being restricted to a particular geographical area4 or by only addressing certain CAD conditions, especially stable angina5 or acute coronary syndrome.6,7

The CLARIFY8,9 registry was developed with the main aim of obtaining worldwide data on the treatment of all CAD outpatients in the setting of daily clinical practice and of identifying the determinants, including HR, of long-term outcomes in this population. Even though HR has been associated with increased cardiovascular risk10 it is not yet a routine component of cardiovascular assessment; furthermore, its prognostic value and to what extent it is applied in clinical practice remains unknown. This paper describes and compares the demographic and clinical characteristics of the Spanish cohort with other western European cohorts.

METHODSCLARIFY is an international prospective registry, launched in 41 countries worldwide. Its main objective is to describe the demographic and clinical characteristics of stable CAD outpatients seen in daily clinical practice by the medical specialists (cardiologists, internists, and primary care physicians) in charge of managing these patients in each participating country. A secondary objective is to develop a risk prediction model by identifying long-term prognostic factors, including resting HR. The CLARIFY study is being conducted in accordance with the principles embodied in the Declaration of Helsinki. The present study was reviewed and approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Hospital Clínico San Carlos in Madrid.

The CLARIFY study population consists of stable CAD outpatients attending primary care centers or specialist units (cardiology and internal medicine) worldwide. In each country, the national coordinators selected the participating centers according to the distribution of coronary patients and the health care organizational structure, such that the sample was representative of the epidemiological patterns in each country. Each selected physician included the first 10 consecutive patients attending his or her center who met the eligibility criteria. The national coordinators of the CLARIFY registry in Spain decided that only cardiologists who were based in hospitals or outpatient centers could participate because these specialists are responsible for making decisions about stable CAD patients. The list of researchers is shown in the supplementary material.

The registry includes stable CAD outpatients with at least 1 of the following conditions: documented myocardial infarction that occurred more than 3 months earlier; at least 1 coronary stenosis blocking>50% of the artery on angiography; chest pain with myocardial ischemia confirmed by stress electrocardiogram, stress echocardiography, or myocardial imaging; coronary artery bypass graft or percutaneous coronary intervention conducted more than 3 months before inclusion. Patients were excluded if they had been hospitalized for cardiovascular disease in the last 3 months, were scheduled for revascularization, or their condition hindered their participation in the study and the 5-year follow-up period.

Patients were recruited between October 2009 and June 2010 worldwide and from April to June 2010 in Spain. All patients will be followed up for 5 years with annual visits. Data collection is by electronic forms translated into the local language. At baseline, patients were evaluated for demographic information, risk factors, lifestyle, medical history, physical examination, current symptoms, data from the most recent tests, and current chronic medical treatments. At the annual visits, this information is updated and data are collected on the patient's clinical course and cardiovascular mortality and morbidity. This is an observational study and thus all the information is collected during daily clinical practice in each center, as documented in the patients’ medical history.

Based on data from previous studies,5 the total size of the sample of the registry was determined by estimating cardiovascular mortality and mortality or cardiovascular events to be 2% and 4.5% per year, respectively. At least 31 000 participants are expected to be selected with an estimated 5% loss to follow-up per year. Thus, the expected number of cardiovascular deaths will be approximately 2300. On the basis of the analysis of HR as a categorical variable (population divided into HR quartiles), we used a conservative approach that compared the highest HR quartile to the other quartiles to establish the risk of cardiovascular mortality. This comparison resulted in a minimum statistical power of 80% to identify a 20% increase in risk for the group with the highest HR. If HR is considered a continuous variable, a power of 90% to detect an instantaneous hazard ratio of 1.06 for each 10 bpm increase in HR would be obtained at a significance level of 5%. In general, each participating country had to recruit a mean of 25 patients (range, 12.5-50) per million population to obtain a representative sample.

The post hoc analysis presented in this article describes the baseline characteristics of the sample in Spain and other western European countries (Germany, Austria, Belgium, Denmark, France, Greece, Ireland, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal, Switzerland, the United Kingdom) participating in the CLARIFY registry. Continuous variables are expressed as mean (standard deviation) or median [interquartile range] according to the data distribution. Categorical variables are expressed as absolute frequencies and percentages. Continuous variables (Spanish subcohort vs western European subcohorts) were compared using simple analysis of variance (ANOVA) or the Kruskal-Wallis test according to the data distribution. Categorical variables were compared using the chi-square test. In all cases, the results were considered significant when P<.05.

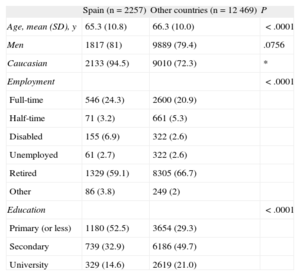

RESULTSThe CLARIFY registry included 33 248 participants from 41 countries, of whom 14 726 were from the western European countries included in the present analysis. A total of 192 cardiologists recruited the 2257 participants from Spain. The demographic characteristics of the patients from Spain and the rest of the sample are summarized in Table 1. The majority of the participants were men (81% in Spain and 79% in the rest of the sample) and mean age was 65 years in the Spanish sample and 66 years in the remaining sample.

Sociodemographic Characteristics

| Spain (n=2257) | Other countries (n=12 469) | P | |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 65.3 (10.8) | 66.3 (10.0) | <.0001 |

| Men | 1817 (81) | 9889 (79.4) | .0756 |

| Caucasian | 2133 (94.5) | 9010 (72.3) | * |

| Employment | <.0001 | ||

| Full-time | 546 (24.3) | 2600 (20.9) | |

| Half-time | 71 (3.2) | 661 (5.3) | |

| Disabled | 155 (6.9) | 322 (2.6) | |

| Unemployed | 61 (2.7) | 322 (2.6) | |

| Retired | 1329 (59.1) | 8305 (66.7) | |

| Other | 86 (3.8) | 249 (2) | |

| Education | <.0001 | ||

| Primary (or less) | 1180 (52.5) | 3654 (29.3) | |

| Secondary | 739 (32.9) | 6186 (49.7) | |

| University | 329 (14.6) | 2619 (21.0) |

SD, standard deviation.

* Not calculated.

Unless otherwise indicated, the data are expressed as No. (%).

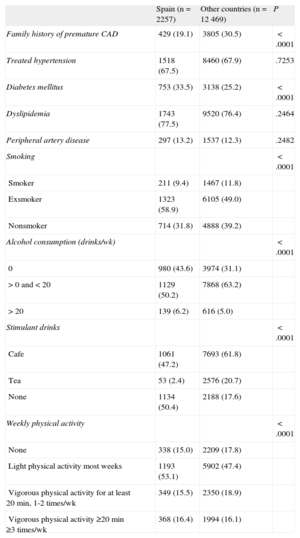

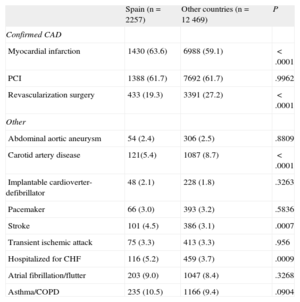

Risk factors and lifestyle habits are shown in Table 2. The percentage of current smokers was lower in Spain than in the other western European countries, and the percentage of exsmokers was higher in Spain (Table 2). In the Spanish sample, 78% of patients had dyslipidemia, 68% had hypertension, 34% had diabetes mellitus (DM), and 13% had peripheral artery disease. The greatest differences between Spain and the other western European countries were in the prevalence of DM (34% vs 25%, P<.0001) and in having a family history of premature CAD (19% vs 31%, P<.0001). Myocardial infarction (64% vs 60%, P<.0001) and stroke (5% vs 3%, P=.0007) were more common in Spain than in the rest of the sample, whereas carotid artery disease was less common in Spain (5% vs 9%, P<.0001) (Table 3). Tables 4 and 5 show the clinical profile and baseline symptoms of the patients.

Risk Factors and Lifestyle Habits

| Spain (n=2257) | Other countries (n=12 469) | P | |

| Family history of premature CAD | 429 (19.1) | 3805 (30.5) | <.0001 |

| Treated hypertension | 1518 (67.5) | 8460 (67.9) | .7253 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 753 (33.5) | 3138 (25.2) | <.0001 |

| Dyslipidemia | 1743 (77.5) | 9520 (76.4) | .2464 |

| Peripheral artery disease | 297 (13.2) | 1537 (12.3) | .2482 |

| Smoking | <.0001 | ||

| Smoker | 211 (9.4) | 1467 (11.8) | |

| Exsmoker | 1323 (58.9) | 6105 (49.0) | |

| Nonsmoker | 714 (31.8) | 4888 (39.2) | |

| Alcohol consumption (drinks/wk) | <.0001 | ||

| 0 | 980 (43.6) | 3974 (31.1) | |

| >0 and<20 | 1129 (50.2) | 7868 (63.2) | |

| >20 | 139 (6.2) | 616 (5.0) | |

| Stimulant drinks | <.0001 | ||

| Cafe | 1061 (47.2) | 7693 (61.8) | |

| Tea | 53 (2.4) | 2576 (20.7) | |

| None | 1134 (50.4) | 2188 (17.6) | |

| Weekly physical activity | <.0001 | ||

| None | 338 (15.0) | 2209 (17.8) | |

| Light physical activity most weeks | 1193 (53.1) | 5902 (47.4) | |

| Vigorous physical activity for at least 20 min, 1-2 times/wk | 349 (15.5) | 2350 (18.9) | |

| Vigorous physical activity ≥20 min ≥3 times/wk | 368 (16.4) | 1994 (16.1) |

CAD, coronary artery disease.

Data are expressed as No. (%).

Medical History

| Spain (n=2257) | Other countries (n=12 469) | P | |

| Confirmed CAD | |||

| Myocardial infarction | 1430 (63.6) | 6988 (59.1) | <.0001 |

| PCI | 1388 (61.7) | 7692 (61.7) | .9962 |

| Revascularization surgery | 433 (19.3) | 3391 (27.2) | <.0001 |

| Other | |||

| Abdominal aortic aneurysm | 54 (2.4) | 306 (2.5) | .8809 |

| Carotid artery disease | 121(5.4) | 1087 (8.7) | <.0001 |

| Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator | 48 (2.1) | 228 (1.8) | .3263 |

| Pacemaker | 66 (3.0) | 393 (3.2) | .5836 |

| Stroke | 101 (4.5) | 386 (3.1) | .0007 |

| Transient ischemic attack | 75 (3.3) | 413 (3.3) | .956 |

| Hospitalized for CHF | 116 (5.2) | 459 (3.7) | .0009 |

| Atrial fibrillation/flutter | 203 (9.0) | 1047 (8.4) | .3268 |

| Asthma/COPD | 235 (10.5) | 1166 (9.4) | .0904 |

CAD, coronary artery disease; CHF, congestive heart failure; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

Data are expressed as No. (%).

Baseline Clinical Profile

| Spain (n=2257) | Other countries (n=12 469) | P | |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 27.8 [25.7-30.5] | 27.5 [25.1-30.4] | <.0001 |

| Waist circumference, cm | 99 [91-106] | 99 [90-107] | .9446 |

| SBP, mean (SD), mmHg | 131 (16) | 131 (16) | .3225 |

| DBP, mean (SD), mmHg | 76 (10) | 77 (9) | <.0001 |

| HR by pulse palpation, mean (SD), bpm | 66 (11) | 66 (11) | .0018 |

| HR on ECG, mean (SD), bpm | 65 (11) | 65 (11) | .1046 |

| ECG | |||

| Sinus rhythm | 1942 (93) | 8881(94) | .4721 |

| Atrial fibrillation/flutter | 95 (5) | 387 (4) | |

| Paced rhythm | 48 (2) | 194 (2) | |

| LBBB | 154 (7) | 501(5) | .0002 |

BMI, body mass index; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; ECG, electrocardiogram; HR, heart rate; LBBB, left bundle branch block; SBP, systolic blood pressure; SD, standard deviation.

Unless otherwise indicated, the data are expressed as No. (%) or median [interquartile range].

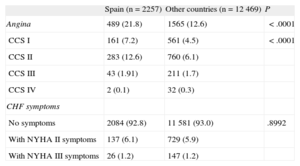

Current Symptoms

| Spain (n=2257) | Other countries (n=12 469) | P | |

| Angina | 489 (21.8) | 1565 (12.6) | <.0001 |

| CCS I | 161 (7.2) | 561 (4.5) | <.0001 |

| CCS II | 283 (12.6) | 760 (6.1) | |

| CCS III | 43 (1.91) | 211 (1.7) | |

| CCS IV | 2 (0.1) | 32 (0.3) | |

| CHF symptoms | |||

| No symptoms | 2084 (92.8) | 11 581 (93.0) | .8992 |

| With NYHA II symptoms | 137 (6.1) | 729 (5.9) | |

| With NYHA III symptoms | 26 (1.2) | 147 (1.2) |

CCS, Canadian Cardiovascular Society class; CHF, congestive heart failure; NYHA, New York Heart Association functional class.

Data are expressed as No. (%).

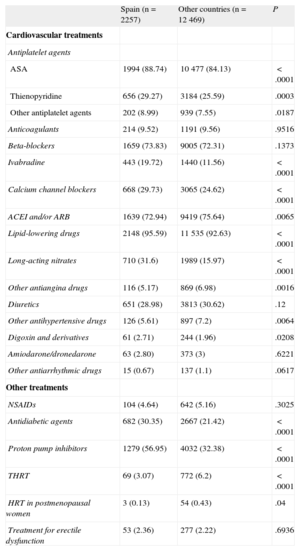

Table 6 shows the treatment the patients were receiving at the time of the baseline visit. The most common treatments in the Spanish sample were lipid-lowering drugs (96%), aspirin (89%), and beta-blockers (74%). The greatest difference between Spain and the other western European countries was in the higher frequency of specific treatments such as ivabradine, antidiabetic agents, long-acting nitrates, and proton pump inhibitors in the Spanish cohort.

Treatments

| Spain (n=2257) | Other countries (n=12 469) | P | |

| Cardiovascular treatments | |||

| Antiplatelet agents | |||

| ASA | 1994 (88.74) | 10 477 (84.13) | <.0001 |

| Thienopyridine | 656 (29.27) | 3184 (25.59) | .0003 |

| Other antiplatelet agents | 202 (8.99) | 939 (7.55) | .0187 |

| Anticoagulants | 214 (9.52) | 1191 (9.56) | .9516 |

| Beta-blockers | 1659 (73.83) | 9005 (72.31) | .1373 |

| Ivabradine | 443 (19.72) | 1440 (11.56) | <.0001 |

| Calcium channel blockers | 668 (29.73) | 3065 (24.62) | <.0001 |

| ACEI and/or ARB | 1639 (72.94) | 9419 (75.64) | .0065 |

| Lipid-lowering drugs | 2148 (95.59) | 11 535 (92.63) | <.0001 |

| Long-acting nitrates | 710 (31.6) | 1989 (15.97) | <.0001 |

| Other antiangina drugs | 116 (5.17) | 869 (6.98) | .0016 |

| Diuretics | 651 (28.98) | 3813 (30.62) | .12 |

| Other antihypertensive drugs | 126 (5.61) | 897 (7.2) | .0064 |

| Digoxin and derivatives | 61 (2.71) | 244 (1.96) | .0208 |

| Amiodarone/dronedarone | 63 (2.80) | 373 (3) | .6221 |

| Other antiarrhythmic drugs | 15 (0.67) | 137 (1.1) | .0617 |

| Other treatments | |||

| NSAIDs | 104 (4.64) | 642 (5.16) | .3025 |

| Antidiabetic agents | 682 (30.35) | 2667 (21.42) | <.0001 |

| Proton pump inhibitors | 1279 (56.95) | 4032 (32.38) | <.0001 |

| THRT | 69 (3.07) | 772 (6.2) | <.0001 |

| HRT in postmenopausal women | 3 (0.13) | 54 (0.43) | .04 |

| Treatment for erectile dysfunction | 53 (2.36) | 277 (2.22) | .6936 |

ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; ARB, angiotensin II receptor antagonists; ASA, acetylsalicylic acid; HRT, hormone replacement therapy; NSAIDs, nonsteroid anti-inflammatory agents; THRT, thyroid hormone replacement therapy.

Data are expressed as No. (%).

The results of this study show that the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the stable CAD patients in the Spanish cohort of the CLARIFY registry are similar to those of patients in the other participating western European countries. These characteristics appear to be representative of the Spanish population with CAD, since they are generally similar to those reported by other studies that also included patients with CAD in both local4 and international settings.11,12

More than half of the participants in the Spanish sample were men with a mean age of approximately 65 years, which is similar to the mean age previously observed in this population.4,11,13 Some significant differences were found between the Spanish cohort and the other cohorts, although in principle these differences were not expected. The observed difference in some demographic characteristics, such as age, may have been the result of minor differences of little importance but which became statistically significant due to the large sample size. The observed differences in educational level may have been partly due to differences in the way education systems are classified in each country. There were also unexpected differences in having a family history of CAD or DM. These differences may have been due to under-reporting by the cardiologists, rather than to a real difference between groups.

Tobacco consumption was low, and the percentage of smokers (9%) was similar to that reported in other Spanish registries on coronary heart disease.4,13 The percentage of smokers was also slightly lower than in the other western European countries, a finding that has also been reported in other international registries that included Spanish patients with coronary heart disease.11,13 Comparative studies conducted in Europe in CAD patients show a decrease in tobacco consumption in Spain over the last 10 years (18% in Spain vs 21% in Europe).14 This trend reflects a change in lifestyle among CAD patients in Europe; the need to decrease tobacco consumption has been demonstrated and remains a fundamental aspect for the secondary prevention of CAD.2

The pattern of other risk factors is consistent with that previously observed in this population.4,11,13,14 Thus, the prevalence of DM in the Spanish cohort was similar to that observed in other registries11,13,14 and somewhat lower than that reported in patients with high cardiovascular risk.15,16 The rate of hypertension was also similar to that reported in other studies11,13 and lower than that observed in patients with acute CAD.16

Although the differences in clinical profile between the Spanish cohort and the western European cohorts in parameters such as body mass index, diastolic blood pressure and HR were statistically significant (P<.05) (Table 4), the absolute value of these differences was of no clinical relevance. The mean blood pressure in all the CLARIFY cohorts was within the range recommended by the clinical practice guidelines2 and was slightly lower than that recently observed in CAD patients in Europe.12 However, the average resting HR (65 bpm) in all the cohorts exceeded the recommended target rate (55-60 bpm).17 Recently published data from the entire CLARIFY registry show that an HR>60 bpm was associated with a higher prevalence and greater severity of angina.9 These data indicate the need for improved treatment to reduce HR in patients with stable angina to the recommended target rate of 60 bpm.17

The most pronounced differences between the Spanish and European cohorts were related to specific treatments. Although demographic and clinical characteristics did not generally differ between cohorts, the differences observed in treatment could indicate different clinical practices in each country, thus underlining the need for an international registry similar to that presented here. Follow-up data from the registry are needed to understand the prognostic implications of these differences. To date, data from the baseline visit only show that there are specific differences in treatments between the Spanish and western European cohorts. These differences mainly involve the use of cardiovascular drugs such as ivabradine and long-acting nitrates, which were more frequently used in the Spanish sample (20% and 32%, respectively) than in the other European countries (12% and 16%, respectively). However, the observed difference in the use of antidiabetic agents (30% in the Spanish cohort and 21% in the other cohorts) could be explained by the higher prevalence of DM recorded in Spain (34% in Spain and 25% in other western European countries). Furthermore, the increased use of proton pump inhibitors in the Spanish cohort is striking compared with the other cohorts and with other treatments. Although the abuse of these drugs in Spain is well known,18,19 the marked difference between Spain and the other countries cannot be explained by differences in age or in the use of medications that increase the risk of bleeding, since both factors are similar in both groups. In the absence of additional data on comorbidities that may be associated with this increase, it can only be speculated that the use of these drugs in Spanish clinical practice must strongly differ from their use in the other western European countries in the registry.

Overall, the pattern of use of cardiovascular drugs reported in the CLARIFY registry is similar to that previously reported for the Spanish population with CAD, with the exception of specific treatments such as beta-blockers and lipid-lowering drugs, whose use is slightly higher than that reported in similar registries.4,11,20 The number of prescriptions for beta-blockers is even higher than that previously observed in patients hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction.21 The clinical practice guidelines recommend beta-blockers in these patients and even in patients with type II diabetes. The widespread use of antiplatelet agents was similar to that observed in the total sample and to that published by other studies,4,12 but was slightly higher than in other registries.20 The level of use is consistent with the clinical guidelines, which recommend antiplatelet therapy in all patients with CAD unless contraindicated.2 The cross-sectional design of the present study does not allow assessment of the degree of nonadherence with clinical practice guidelines in drug prescription and its possible causes; however, this information can be analyzed during follow-up of the registry, which, unlike previous registries,22 has the advantage that it will allow longitudinal and prospective data collection.

Furthermore, this prospective registry is ongoing and we expect to be able to construct a prediction model that includes factors such as DM, dyslipidemia, obesity23 and HR,3 with a demonstrated important prognostic role in the mortality rates of these patients. Finally, the CLARIFY registry will identify and provide patient cohorts that could be of interest to future clinical studies on improving the management of CAD. It would also be of interest to assess whether there are differences between specific subgroups, since there appear to be differences, for example, between men and women in the control of risk factors after an acute coronary episode24 despite their receiving similar treatment.24,25

Strengths and LimitationsSome limitations should be considered when interpreting the results of this study, such as the use of convenience sampling rather than randomized sampling to select the centers and patients. The use of this method raises the issue of whether the sample is representative of the population under study. However, several aspects can be cited in favor of its representativeness, such as the large number of patients enrolled in the study and, in particular, the similarity of its results with those of other studies in this patient population. Despite these limitations, the registry has several strengths, including the large number of participating countries, making the results more generalizable. The CLARIFY registry is not restricted to a particular geographical area and provides information on daily clinical practice in stable CAD patients.

CONCLUSIONSThe baseline data provided by the CLARIFY registry indicate that the stable CAD patients in the Spanish sample appear to be representative of the Spanish population with CAD and are similar to stable CAD patients in other western European countries. The results of the 5-year follow-up will provide information on how these patients are managed in clinical practice and the degree of adherence to the recommendations of the clinical practice guidelines, leading to improvements in the treatment of this patient population.

FUNDINGLaboratorios Servier S.L.

CONFLICTS OF INTERESTNone declared.

In Spain, the CLARIFY registry was organized and managed by the Spanish Society of Cardiology via its Research Agency, which was funded by Laboratorios Servier S.L. Data analysis was conducted by the Robertson Centre for Biostatistics at Glasgow University, UK. We would like to thank Teresa Hernando (Cociente S.L.) for her assistance in writing this article.