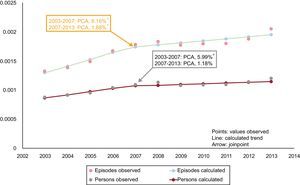

We read with interest the article by López-Messa et al.1 Although the time frame of their study is slightly longer and covers a greater number of conditions, it shares some aspects with our work published in Revista Española de Cardiología2 on the population of the Region of Murcia (RM). Both studies address hospitalizations for heart failure with the same tool–joinpoint regression–and both show a growing trend with an inflection point in 2007 (Figure). This finding is of interest because the same change is shown by 2 nonbordering autonomous communities with the same health care system.

Although it is true that crude rates are the only true rates, in processes mainly affecting a specific population group (eg, older than 64 years) that is increasing and whose weight, in the total population, varies greatly among autonomous communities (representing 14.5% in the RM in 2013 and 23.3% in Castile and León), the results should be standardized by age and sex. Such standardization allows elimination of the influence of both factors and a comparison of distinct populations. In 2013, hospitalizations (crude rates) comprised 2.26/1000 population in the RM and 3.39/1000 population in Castile and León. If the RM had the same population structure as Castile and León, its hospitalizations (standardized) would have been 3.95/1000 population, a figure that reverses the conclusion of the comparison. Thus, standardization is essential before results can be compared. In addition, our study included hospitalizations funded by the Spanish National Health System in public-private hospitals (which increased the total number of admissions in the period by 5.4%) and calculated health care episodes by taking into account transfers between hospitals (which decreased total admissions by 1.5%). Although this last factor has little effect on this condition in the RM, it is more important in others (between 3% and 10% for ischemic stroke3 and between 13% and 24% for acute myocardial infarction and unstable angina4).

Given the importance of between-population comparisons, a useful addition would be the development of other simple indicators that can complement the current ones. One of these could be the rate of individual patients generating the hospitalizations.5 In Spain, the rate of patients hospitalized for heart failure varied between 1.1 and 1.8/1000 population between 2003 and 2013, and its trend also showed an inflection point in 2007. However, the annual percentage increase was less than that of hospitalizations in both periods and ceased to be statistically significant from 2007 (Figure), which would reflect the weight of persons with recurrent admissions.

Independently of these considerations, both studies agree on the importance of researching population indicators and their trends (eg, hospitalizations, hospital readmissions independent of hospital discharge, survival), particularly given that this statistical information is accessible with appropriate reliability and can permit the design, implementation, and comparative assessment of preventive and health care policies adapted to each population setting.6

.